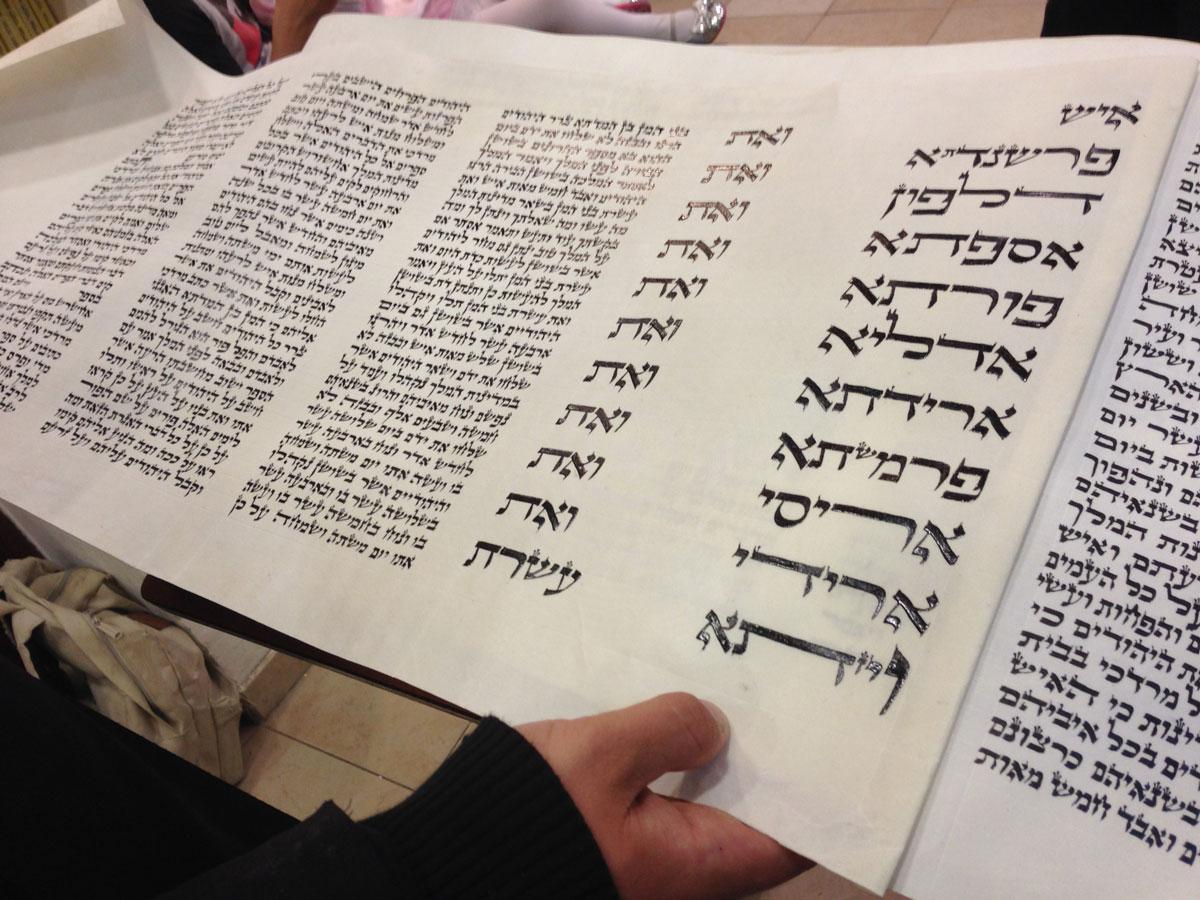

Orthodox Jewish men in costume read from a scroll of the biblical Book of Esther for the Jewish carnival holiday of Purim. The story tells the tale of an ancient Persian king whose viceroy hatches a plot to kill the Jews of the kingdom, a plot that is thwarted by Queen Esther.

Though Israel and Iran are archenemies, they’re both in celebration mode this week — and some Israelis and Iranians see each other reflected in their holidays.

In Israel, Jews this week celebrated the holiday of Purim. The centerpiece of the holiday is the biblical Book of Esther, a tale about an ancient Persian king whose evil viceroy, Haman, hatches a plot to kill the Jews of the kingdom. At the last minute, Queen Esther comes to the rescue, thwarts the evildoer’s plan and the Jews are saved.

For most Israeli Jews, the holiday is an excuse to dress in costume and party. But for some in Israel — and in Iran — this story from the Bible is very much alive.

“Both sides are making ridiculous use of the Book of Esther in order to fight the other,” said Thamar Eilam Gindin, an Israeli expert on Iran and on the Book of Esther, who teaches at the Shalem College of Liberal Arts in Jerusalem.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu brought up the biblical story in his contentious speech to Congress last year to urge US lawmakers to reject a deal with Iran over its nuclear program.

In his speech the day before the Jewish holiday, Netanyahu evoked the Book of Esther. “We'll read of a powerful Persian viceroy named Haman, who plotted to destroy the Jewish people some 2,500 years ago,” Netanyahu said.

“Today the Jewish people face another attempt by yet another Persian potentate to destroy us,” Netanyahu said, calling Iran’s supreme leader a modern day Haman.

Eilam Gindin said Netanyahu’s comparison embarrassed her.

“First of all — assuming the story is real — Haman was not Persian. He was not Iranian. He was Amelekite, that is, a Semite,” Eilam Gindin said.

A minor point, perhaps. But from a historical point of view, there is no written record outside the Bible of the events of the Book of Esther ever taking place.

An older Persian legend has a very similar plot line, though, and the Book of Esther could be a Jewish spin on that Persian tale, Eilam Gindin said.

No historical sources outside the Bible mention a plot to kill the Jews in ancient Persia; Jews aren’t even mentioned in ancient Persian sources until the 3rd century C.E.

“Maybe we weren’t as important as we like to think,” Eilam Gindin said, referring to her Jewish co-religionists. “We survived, our book survived, we’re important now. But at that time, we were just another ethnic group or nationality in the empire.”

Meanwhile, in Iran, some have cast the Book of Esther in an anti-Semitic context, Eilam Gindin said.

At the end of the Book of Esther, after the Jews are saved, they are given royal permission to go on a killing spree against their enemies.

Eilam Gindin admits it is not the nicest part of the book, and it may not reflect an actual historical event. But there are references in Iran to the Jewish holiday as “the holiday of killing Iranians,” and some refer to the events of the Book of Esther as the “Iranian Holocaust.”

One YouTube video in Iran claims this is the context for the Iranian new year holiday of Nowruz being celebrated now.

On the 13th and final day of the holiday, Iranians leave the house and picnic. This video — as well as some respectable Iranian news sites, Eilam Gindin said — claim the tradition is meant to recall the ancient Persians who ran away from the massacring Jews of the biblical story.

“This is why we go out on the 13th day,” the narrator of the video says, “lest we stay at home and be massacred.”

Eilam Gindin insists that modern-day politicized or anti-Semitic readings of the Book of Esther do not reflect the thousands of years of historical connection between Jews and Persians.

“Israel and Iran were best friends and most loyal allies until the Islamic revolution,” Eilam Gindin said. “Jews lived in Iran in relative peace for a long time. Jews in Iran today live in peace. They usually live on good terms with their neighbors. Most Iranians are not anti-Semitic or anti-Israel. The regime's official stance is anti-Zionist, not anti-Jewish.”

Eilam Gindin wrote an annotated version of the biblical story called “The Book of Esther Unmasked.” In it, she describes the story’s historical and linguistic context — the Persian word plays in the biblical tale — the biblical book's historically accurate descriptions of the ancient Persian royal court as it really was.

None of this, Eilam Gindin said, is about enmity.

“My goal is to build a bridge between the two nations,” Eilam Gindin said. “We have been allies for so much of history. For the last 37 years because of the political enmity, some people have been brainwashed on both sides to believe that the other side is bad. Yes, we are political enemies and there are bad people on both sides, but the nations are not enemies. And the more Israelis know about Iran, and the more Iranians know about Israel and Judaism, we just have to see, we’re people.”

Eilam Gindin has started a crowdfunding campaign to translate her book into Persian. She’d like Iranians to be able to download her book for free online.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!