Zika’s advantage in Brazil’s cities? People aren’t scared of mosquitoes.

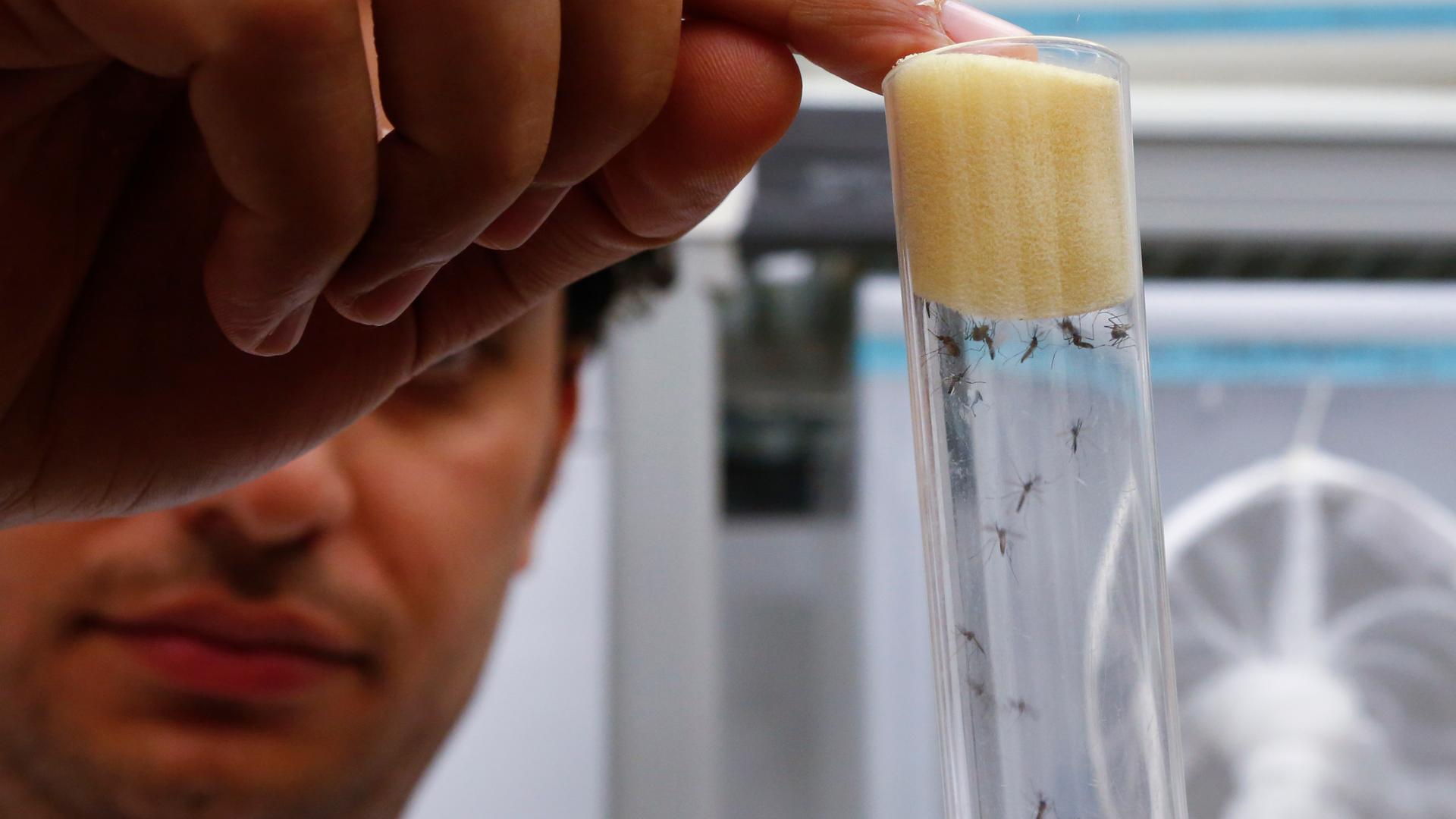

A scientist displays Aedes aegypti mosquitoes inside the International Atomic Energy Agency's insect pest control laboratory, Austria.

The Kellerman family recently caved. Stephany Kellerman went to the pharmacy and bought a bottle of insect repellent.

Kellerman thought the decision was wise. People all around her in the Divineia favela in Sao Paulo, Brazil’s largest city, were falling sick with dengue. Then there was this new disease — Zika — with all its scary unknowns. And she has her 8-month-old daughter to worry about. So she coughed up about $2.70 for a bottle.

Still, Kellerman’s father refuses to wear the repellent, and the family sees no need to invest in mosquito nets, which could prevent the odd nighttime bite.

As this country battles a health crisis over several mosquito-borne diseases (including the Zika virus, suspected of causing birth defects in infected babies), Sao Paulo faces an additional challenge: Many residents view mosquitoes as largely a problem for the “interior” and the northeast of the country. Their southeastern coastal metropolis, they believe, is safe from the scourge of mosquitoes and the deadly diseases they carry.

“They use those [mosquito nets] more in the interior,” Kellerman said. “Here in Sao Paulo, the weather isn’t right for mosquitoes. Today it’s hot, but tomorrow it might be cold and rainy.”

This couldn’t be further from the truth. The Aedes aegypti mosquito, which carries Zika, dengue and the chikungunya virus, actually thrives in city landscapes, so much so that it is known as an “urban mosquito.” Cities like São Paulo, which is regularly soaked by tropical rainstorms, provide millions of ideal breeding sites for the bloodsuckers, said Catherine Hill, a medical entomology professor and mosquito expert at Purdue University in Indiana.

“They’re exquisitely adapted to exploiting human-modified environments and living in close proximity with their human hosts,” Hill said. “Humans create breeding sites for Aedes aegypti. Aedes likes to breed in containers that will fill with water.”

Margareth Capurro, a professor of molecular biology at the University of Sao Paulo and one of Brazil’s foremost mosquito experts, said residents of the megacity are lulled into a false sense of security by their apparent distance from the epicenter of the mosquito-borne disease crisis some 1,500 miles away.

“Above São Paulo [people think] everything is ‘northeast,’ and ‘I don’t know what’s happening up there,’” Capurro said. “This is a very São Paulo way of thinking. It’s a cultural thing.”

Jackie Gomes, a 23-year-old student and resident of Paraisopolis, São Paulo's largest favela, said this mindset permeates her group of friends and her family.

Gomes said she’s never seen her friends apply mosquito repellent. She said the drugstores of Paraisopolis have recently stocked up on repellent that claims on the packaging to be “anti-Zika” and “anti-dengue,” but that nobody’s buying it.

“They have all these special bracelets that repel mosquitoes, they have mosquito repellent, but nobody buys it, I don’t see anybody buying it,” Gomes said.

As is common in favelas in the southeast, many residents of Paraisopolis moved there from Brazil’s historically poorer northeast.

Gomes, whose family is originally from the northeastern state of Pernambuco, said the favela residents feel they’re not just farther away from the mosquitoes that carry dengue and Zika, but that they’re also insulated from the socio-economic problems they left behind.

“People believe that we are protected here, more than anything,” Gomes said. “That it doesn’t really matter if we have an explosion of Zika in the city, that we’re going to be taken care of by the government.”

Certainly, the Brazilian government has mobilized across Brazil and all over São Paulo. Since February, teams of health workers have been going door-to-door in neighborhoods thought to be playing host to disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Part of their job has been to convince residents that mosquitoes, like people, are actually pretty partial to city living.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!