An anti-immigrant political movement that sparked an election day riot — 150 years ago

Joseph Keppler’s cartoon “Looking Backward,” which appeared in the magazine Puck in 1893, depicted American descendants of immigrants denying entry to the country’s next generation of newcomers. Though the Know Nothing Party largely disbanded after the 1856 presidential elections, their anti-immigrant platform endured for many years.

Kentucky’s current political office holders are not necessarily kind to the nation’s newcomers. Before Matt Bevin entered the governor’s mansion, he joined the chorus of Republican governors who claimed they’d refuse the resettlement of Syrian refugees after last November’s terrorist attacks in Paris.

At the same time, Kentucky senator — and until recently, GOP presidential candidate — Rand Paul supported efforts to deny visas to refugees to the United States from countries with “significant jihadist movements.”

But anxiety about the foreign-born, religion and national security is nothing new in Kentucky.

It was nearly 160 years ago, but many of the descendants of immigrants who gathered in Louisville back then still remember Bloody Monday. They commemorated the day last March. In 1855, 22 people were killed and many more injured — most of them Irish and German immigrants to America — during an election day brawl in Louisville.

The Know Nothing Party, also known as the “American Party” or the “Order of the Star Spangled Banner,” was built on concerns that immigrants to the country, particularly Irish and German Catholics, threatened the very essence of what it meant to be “American.” From the 1830s to the 1850s, the Know Nothings espoused their anti-immigrant platform in the pages of the country’s newspapers, from the pulpits of its lecture halls, and perhaps most significantly, at the polls.

Tension over the role that immigrants ought to play in Kentucky’s elections had been simmering for years before the “Bloody Monday” riot on election day in 1855. During Kentucky’s Constitutional Convention of 1849, attendees fiercely debated whether foreign-born Kentuckians ought to have the right to vote at all, and if so, for how many years they must have lived in the state before being permitted to vote or run for office.

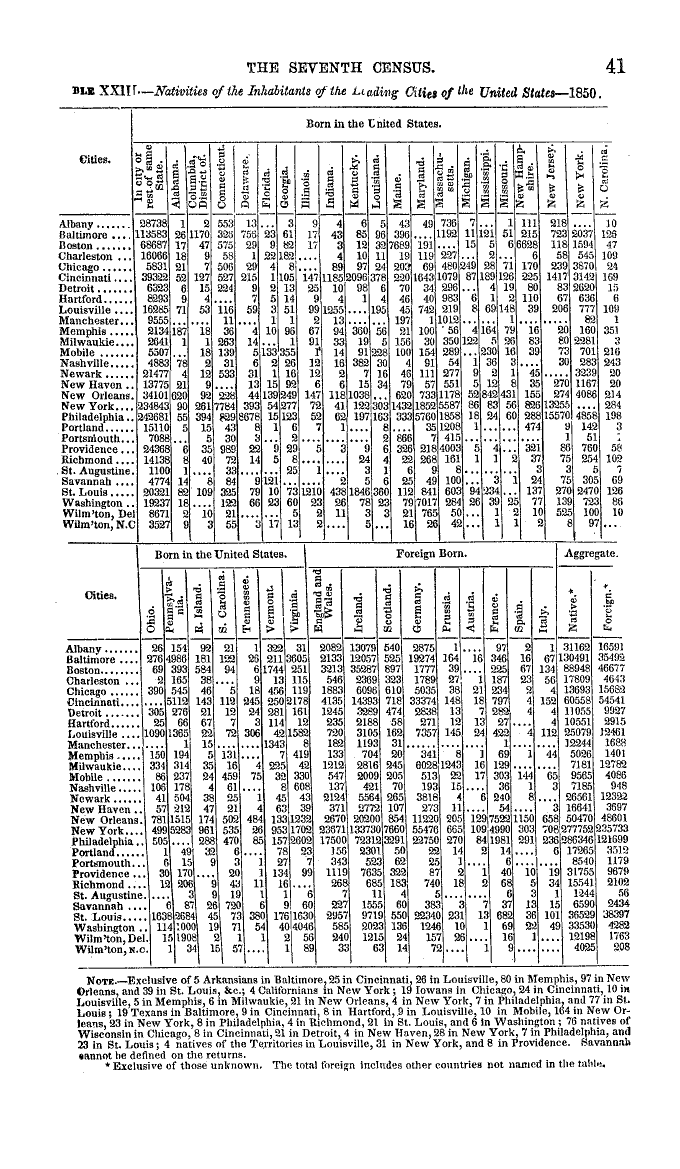

A string of victories for Know Nothing candidates in local and state elections around the country during the early 1850s mobilized support for the party in Kentucky. Kentucky historian Charles E. Deusner writes in the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society that native Kentuckians had anxiety about the growing numbers of immigrants in Louisville in particular, who they believed put undue stress on the city’s prisons, hospitals and almshouses.

From 1854 to 1855, candidates on the Know Nothing ticket won seats in Jefferson, Covington and Lexington, as well as Louisville’s municipal and county elections, and took the Louisville mayor’s office.

Rally to put down an organization of Jesuit Bishops, Priests, and other Papists, who aim by secret oaths and horrid perjuries and midnight plotting to sap the foundation of our political edifices — state and national.

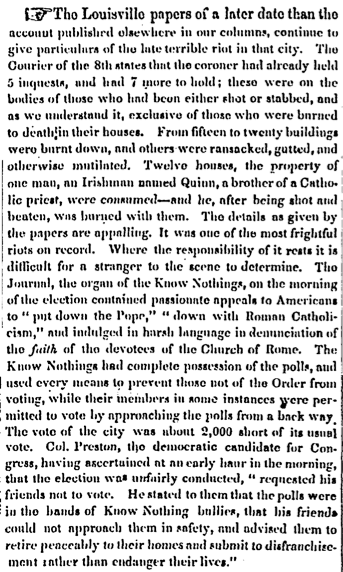

Local opponents of the Know Nothing party tried, to no avail, to meet with Know Nothing party members to ensure that naturalized immigrant voters would have uninterrupted access to the polls. But by the time voting began on the morning of August 6, 1855, armed guards stood before the voting booths, intimidated voters who failed to utter passwords agreed upon by local Know Nothings, and refused entry to individuals dressed in clothes or speaking with accents that marked them as “foreign.”

Before long, voter intimidation turned into outright violence. Know Nothing supporters, who outnumbered immigrants and were better armed, beat, stabbed, lynched and shot Irish and German immigrants. They vandalized and set fire to immigrant-owned homes, businesses and storefronts. When the riot turned toward the Catholic Church, the town’s mayor and other prominent community members convinced them to turn back.

Newspaper reports published in the days after the riot featured mixed interpretations of what occurred and who was responsible. Papers in support of the Know Nothing party claimed that it was Irish immigrants who planned a premeditated attack against native-born Americans. In these accounts, the Know Nothings claimed the riot as an example of a larger plot of immigrant violence against Americans and proof that immigrants ought to be barred not only from the electoral process, but also from the country.

Papers opposing the Know Nothing Party, meanwhile, reported that the party had been strategizing for weeks to limit as much as possible the number of Irish and German immigrants arriving at the polls by any means necessary — including violence.

It remains unknown who struck “Bloody Monday’s” first blow. Regardless, a wave of violence came in its wake. Within a year of the election day riot in Louisville, incidents of anti-immigrant violence associated with the Know Nothing party occurred in Chicago, St. Louis, Columbus, Cincinnati and New Orleans.

The anti-immigrant violence and voter intimidation of Bloody Monday brought about an overwhelming electoral victory for the Know Nothing gubernatorial candidate in Kentucky. But the following year’s presidential election of 1856, which was a disaster for Know Nothing candidate Millard Fillmore, marked the beginning of the end of the party as a viable political force. Although anti-immigrant sentiment has never been far from American politics, the country’s division over slavery during the Civil War — and the fact that thousands of immigrants fought in the war — stalled the Know Nothings and their momentum.

The Know Nothings were not the only ones to leave Kentucky. In her study Nativism in Kentucky to 1860, Agnes Geraldine McGann writes that hundreds of Louisville’s immigrants left the city after the election day riot of 1855. Today, recent arrivals to the state are speaking up and defining on their own terms what it means to be a Kentuckian.

This story was produced in partnership with the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!