Improving water sources, sanitation facilities and poverty alleviation may not be the solution to Brazil’s Zika outbreak

A Brazilian soldier uses pesticide as he inspects a house during an operation against the Aedes aegypti mosquito in Recife, Brazil, January 27, 2016.

Since the outbreak of the Zika virus in Brazil, many have conveniently blamed inadequate water supplies and poor sanitation facilities especially in poor and rural areas as the major factors behind the crisis.

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that large populations of Aedes aegypti, the mosquito that spreads the Zika virus, “are often associated with poor water supply and inadequate sanitation and waste disposal services."

According to the international health group, water piped to households is preferable to water drawn from wells, communal standpipes, rooftop catchments and other water-storage systems. The ultimate goal is to eliminate water-storage containers and solid waste that could contain water. The Aedes aegypti breeds in stagnant water.

However, a look at some data and studies suggests that the relationship between poverty and the disease is not as strong as many would think.

Data on the Zika virus is limited — it was not seen as a threat in the past compared to other mosquito-borne diseases, such as dengue fever and Chikungunya virus which have a much higher fatality rate. The Zika virus only caught attention last year when researchers started to link the virus to microcephaly, a birth defect where a baby is born with an abnormally small head.

Fortunately we have a lot more data about dengue as the disease has increased 30-fold over the last 50 years, infecting 50 to 100 million people annually. Dengue is also spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, hence a reduction or increase in dengue would mean the same for Zika.

According to a scientific report that studies the epidemiology of dengue in the Americas from 1980 to 2007, Brazil had one of the highest incidence rates (number of new cases per population) of dengue in Latin America.

In 2015, Brazil continued to lead the region with an incidence rate of 820 cases per 100,000 population, according to WHO data.

However, access to an improved water source in rural Brazil is fairly high in the region. Eighty-seven percent of the rural population in Brazil enjoy improved water sources — which refer to piped water on premises or other protected drinking water sources.

In Paraguay, 95 percent of its rural population have access to improved water sources, but the dengue incidence rate there was 733 in 2015, one of the highest in the region.

If access to safe water does not reduce dengue, how about sanitation?

Brazil is among the worst countries in Latin America with only 52 percent of its rural population having access to improved sanitation facilities, just ahead of Guatemala and Bolivia.

Does it mean that sanitation facilities have a stronger relationship with dengue?

Not really, because Paraguay shows the contrary. Seventy-eight percent of its rural population have access to improved sanitation facilities.

A comparison that uses only the data of a single year may not be accurate as the number of dengue cases can fluctuate greatly every year.

Let's look at some more comprehensive research.

A study published in the Pathogens and Global Health medical journal in 2015 has reviewed 12 studies about a dengue-poverty relationship and found no clear associations between the two.

The 12 studies were selected from 260 peer-reviewed articles. Seven of them were done in Brazil.

“While nine of the 12 studies demonstrated some positive associations between measures of dengue and poverty (measured inconsistently through income, education, structural housing condition, overcrowding and socioeconomic status), nine also presented null results and five with negative results.

“Of the five studies relating to access to water and sanitation, four reported null associations,” said the paper.

Out of the four that failed to establish water and sanitation as the factors of dengue, three were conducted in Brazil.

The study found that income and physical housing conditions were more consistently correlated with dengue outcomes than other poverty indicators.

Singapore, the only developed country in the tropics with an income per capita five times higher than Brazil, is another interesting case.

The island city-state in Southeast Asia has been providing improved water sources to its entire population since 1990. In terms of sanitation, 99 percent of its population had access to improved sanitation facilities in 1990, and the number reached 100 percent in 2015.

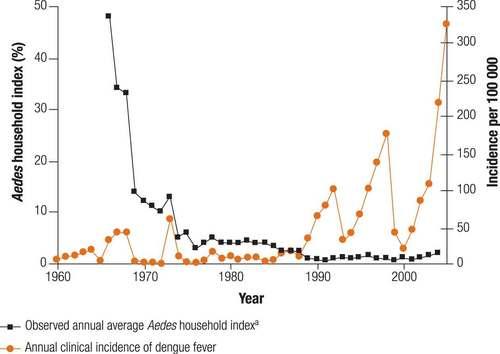

Nevertheless Singaporeans have experienced a rapid re-emergence of dengue cases since 1990 despite a successful vector control program that has reduced the percentage of all properties with breeding sites of Aedes mosquitoes to almost zero.

The Singaporean government even warned that the number of dengue cases could reach record levels in 2016.

Does all this suggest that attention should not be given to safe water access and sanitation infrastructures? Certainly not.

But the findings do remind us that improved living conditions and poverty alleviation are not enough. The circumstances and factors that give rise to the diseases are much more complex and dynamic.

The absence of a strong link between poverty and dengue or Zika could be a good thing because diseases that are deemed to predominantly affect the poor often receive less funding for research.

This phenomenon is known as the 10/90 gap — an important international finding in 1990 that stated less than 10 percent of worldwide resources devoted to health research were allocated in developing countries, where over 90 percent of all preventable deaths worldwide occurred.