70 years later, US World War II veterans still separated from family in the Philippines have new hope

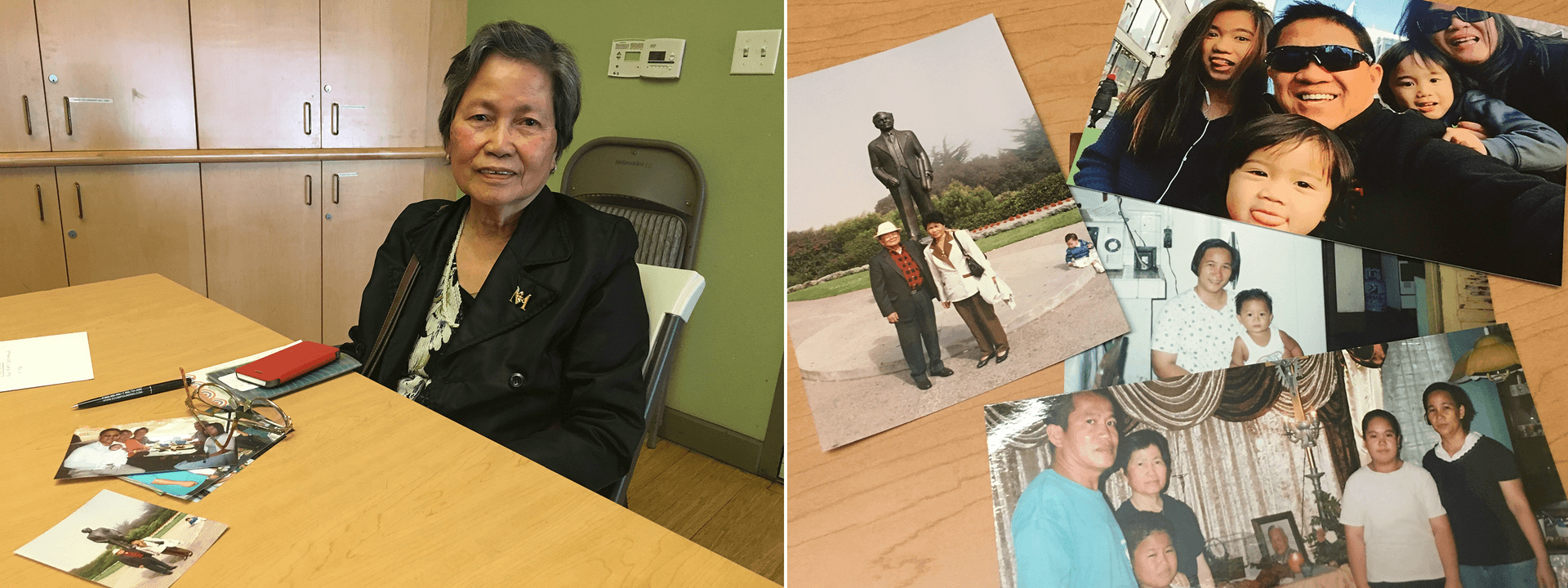

Felix Junia, 89, is hoping to bring his daughters, Precilla and Alicia, to the United States through the Filipino World War II Veterans Parole Program. He was a military police officer at Clark Air Force Base, a former US facility in the Philippines, in the 1940s.

On a recent afternoon at the Veterans Equity Center in San Francisco, men and women in their 70s, 80s and 90s gather around a meeting hall. Tables are organized into a U-shape around the afternoon’s main event: bingo.

This monthly social gathering brings together Filipino seniors. Some of them are World War II veterans or are the spouses of veterans.

US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) estimate some 2,000 to 6,000 veterans nationwide could benefit from the program and advocates say they welcome its rollout, which began in June.

But they also fear the program may have come too late for many.

Lou Tancinco, an immigration attorney in San Francisco, says those who qualify for the program are now in their 80s and 90s — a time when they need help and care from their children. Many more have passed away.

“[The] parole program is very important for the Filipino veterans who suffered long years of separation from their family members, waiting for their petitions to become current. Just like other immigrants, family unification is the ultimate goal,” says Tancinco. “I’m talking about the veterans who have been in isolation for a long time. I’m talking about the widows who don’t have any family members here.”

An estimated 250,000 Filipino soldiers responded to a call-to-arms from the United States and the Philippine governments during World War II. At the time, the Philippines was a colony of the US and was under the threat of Japanese occupation. These Filipino soldiers became part of the United States Armed Forces of the Far East.

Filipinos joined four groups: the Old Philippine Scouts, the Commonwealth Army Of The Philippines, Guerilla Service and the New Philippine Scouts. The groups were formed at different times during the war: Some servicemen fought alongside US troops in battles; others joined after the end of the war to help the US maintain its presence in Asia.

At the Center’s bingo event, Maternidad Comoda, 79, is chatting with her friends. Her husband, Custodio, enlisted with the New Philippine Scouts, a unit that served with the US Armed Forces from 1945 to 1947.

Maternidad says her husband went through training and was later assigned to office work; he kept records for his unit. He was 17 at the time.

“I saw a letter among his files: ‘You’re entitled to benefits from the US government,’” says Maternidad.

But Custodio would not see any of those benefits until later in life. The US government initially said that Filipino soldiers fighting for them would receive US citizenship and be considered for veterans benefits. But lawmakers later stripped Filipino World War II veterans of those benefits. Tancinco says Filipinos were the only group that was denied full US veteran status among soldiers from more than 60 other countries who served with the US.

The Filipino veterans fought to gain back benefits and obtained some incremental victories.

The Comodas moved to the US after Congress passed a law in 1990 that allowed Filipino veterans to immigrate and gives them the option of becoming citizens. But veterans still had to enter the complex immigration system, with its long queues, to bring their immediate family with them.

The plight of these veterans has been a galvanizing issue for many Filipinos in the US. In 2009, there was another victory: Congress passed a law that provided one-time compensation to Filipino World War II veterans. In California this year, advocates celebrated the inclusion of the role of Filipinos during World War II in high school history curriculum.

The Comodas arrived in San Francisco in 1992. Maternidad says her husband wanted to live in the US for better work opportunities. Custodio tried to bring the whole family at the same time, but because their daughters were by this time over 21, only Maternidad was approved.

Their two daughters had already finished college so Maternidad says she felt at peace with their decision to move away. But she always thought they would soon follow. She and her husband filed petitions as soon as they arrived in the US. Like other Filipino veteran families, it never occurred to them that their wait could be 20 years.

Tancinco, the immigration attorney, says there are a limited number of visas allowed each year for non-immediate family, which includes siblings or married children or those over 21 years old. This creates a huge backlog. This fiscal year, USCIS will issue a maximum of 226,000 “family-sponsored preference visas” and has a per country limit of about 25,620. Last fiscal year, the Philippines had more than 400,000 people on the waitlist.

As each of the Comodas’ daughters got married, the wait times grew even longer. One of Maternidad’s daughters joined her in San Francisco in 2001 with a different kind of visa entirely. But in 2008, Custodio died, before her second daughter could join them. After her husband’s death, Maternidad believed her other daughter would never be able to join them: A veteran’s death also meant the end of a veteran’s visa petition.

But the new parole program allows spouses of veterans who have died, like Maternidad, to reinstate their applications.

“My hope was reignited,” Maternidad says. “I was happy because my other daughter can come here, so that we can all be together.”

But Tancinco says the parole program “is not all encompassing. There are some limitations.”

It’s a complicated process, and Tancinco says many of the elderly veterans and spouses she has recently spoken with don’t fully understand the program.

“They’ve reached the point with their health condition that they can no longer comprehend whether or not this is really good for them anymore,” she says. “They’ve just gotten used to waiting.”

Felix Junia, 89, also served with the New Philippine Scouts. He was sent to Okinawa, Japan, and later served as a military police officer at Clark Air Force Base, a former US facility in the Philippines. He came to the US with his wife Cristeta in 1994. When they first arrived, they tried to bring their son. But he died of a brain tumor before they had the chance.

“When the visa came, he was already dead,” says Junia. He says when his son died, he wasn’t able to return for the funeral.

Junia and Cristeta have been trying to petition for visas for their two daughters since 2007.

Junia says he’s looking forward to having his daughters around — he’s had to deal with numerous health complications in recent years and his wife is 78 years old. They have only been able to visit the Philippines every few years.

“I wanted them to come here so that we would have someone here,” he says. “It’s just the two of us.”

For the Comodas, qualifying for the program is also bittersweet because Custodio is not here. Maternidad has started the process of getting her daughter, Mercy, through the parole program. But she’s still worried.

“Sometimes I ask myself, what happens if the [application] doesn’t go through and something happens to me?” says Maternidad. “I’m already almost 80. It’s hard that we’re not all together.”