They’ve spent 30 years fighting for diversity in the arts — in gorilla masks

Kathe and Frida, two founding members of the Guerrilla Girls, are in Minneapolis this week to plaster the downtown theater district in their messages about inequality.

Before there were hashtags, there were the Guerrilla Girls. They have Instagram and Twitter and Facebook and all those social media things. But what really gets them excited is taking up physical space, on the streets, where they can be unavoidable.

And now they've got space in the museums as well. Galleries and performance spaces across Minneapolis are featuring the work of the Guerrilla Girls, as well as other art related to social justice and inequality.

They hide their identities behind gorilla masks and made-up names: Frida (as in Frida Kahlo) and Kathe (as in Käthe Kollwitz) are two of the founders of the anonymous group, which has cycled in and out some 55 members over 30 years.

"When I first started out as an artist, I realized all the opportunities and certainly all the money were going one after another to white men," says Frida. "What we realized in the 1980s is that the message just wasn't getting through."

They gained notoriety after 1984, when they lampooned an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that was supposed to be a survey of the most contemporary art of the world. The exhibit of 169 artists featured 13 women and no people of color.

The group began — anonymously — producing posters and events to expose some of the most egregious disparities in the art world. It turns out their work stayed relevant for decades.

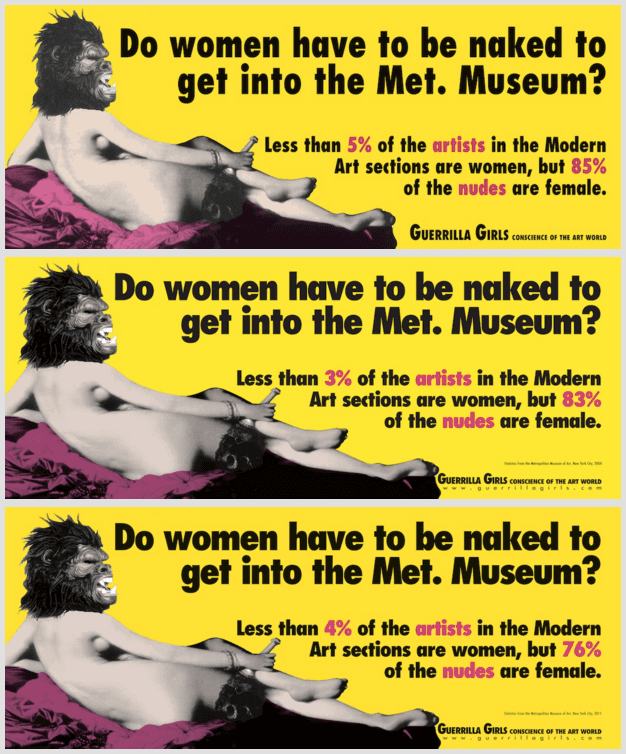

These posters, critiquing the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, are from 1985, 2005 and 2012:

Since that first moment of activist art, not much has been off limits. The Guerrilla Girls have tackled women's representation in art, but also wealth disparities, race in Hollywood and marriage equality with exhibits in cities around the world.

"Early on, we were criticized for not making art. And we don't care," says Frida.

From their guerrilla beginnings, they began taking on more collaborative projects. This week, they're in Minneapolis for events across the city. Their posters are being plastered on downtown buildings and as three billboards, and being put up in the front window of participating institutions.

For a group of anonymous art activists, collaborating with the institutions they are critiquing can be fraught. Frida says she was surprised that Minneapolis art spaces, like the Walker and Minneapolis Institute of Art, not only invited the Guerrilla Girls, but featured their work without interference. This video is showing inside the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA).

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3D9v_xD3oyQCE

"Many of the people in these institutions do care about these issues," says Kathe.

And she sees the Guerrilla Girls' work — the stark, lo-fi, grabby words and images — starting to make a difference. From the time they began their evaluation of the MIA's offerings, they've increased the diversity of artists on offer.

Before the Guerrilla Girls came to town, the MIA opened an exhibit that surveys art across the country, but with an eye to mid-career artists who do not yet have national recognition. Bypassing the collector and donor model that dominate most museums yielded a much more diverse body of work.

"A history of culture that only includes the voices of white men is the history of power, not the history of culture," says Frida. "It's time for the institutions to change. We're ready, we're able. We're important."

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DFxBQB2fUl_g

The Guerrilla Girls' week in Minneapolis concludes March 5 with a performance and discussion at the State Theater.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!