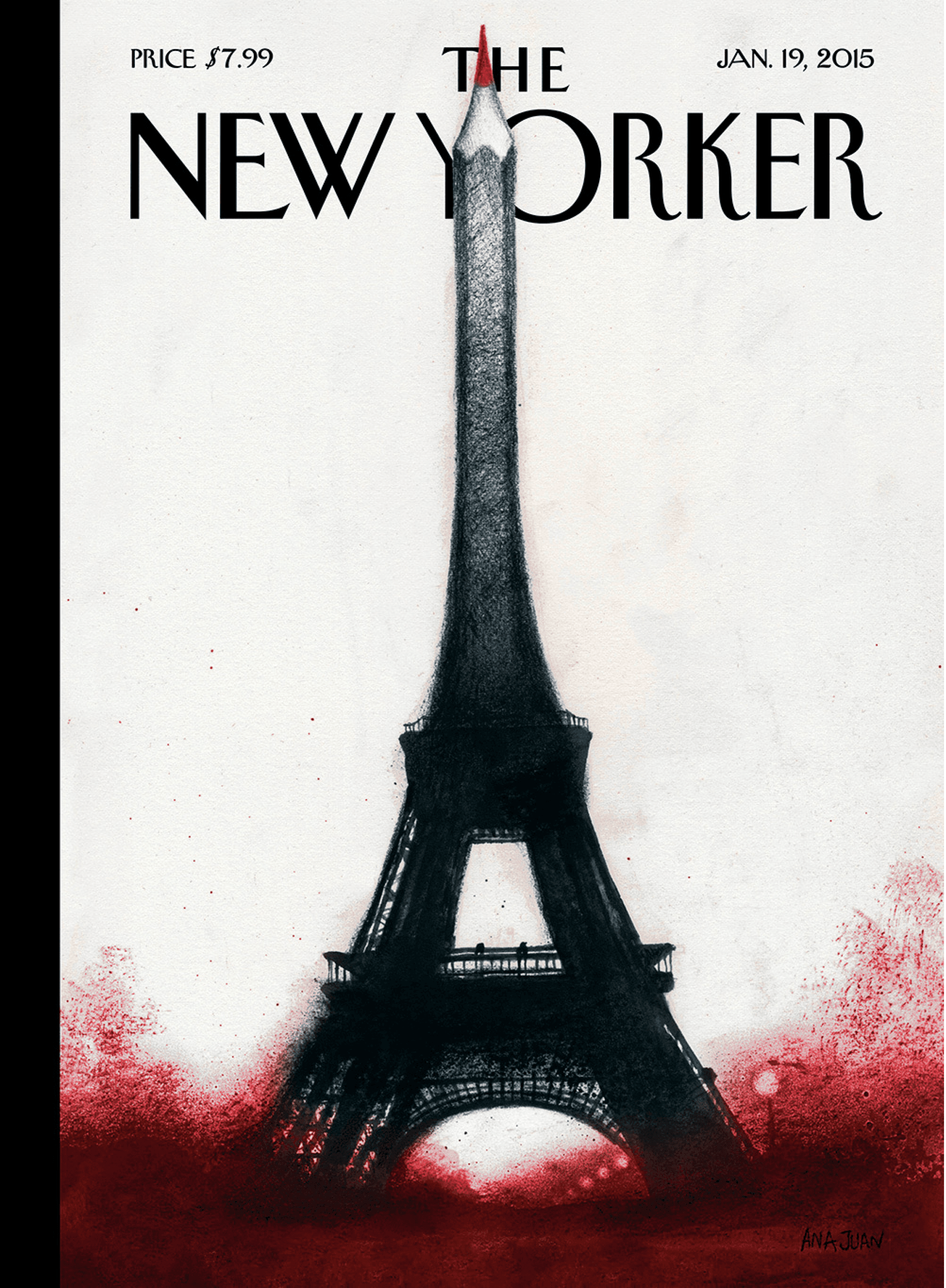

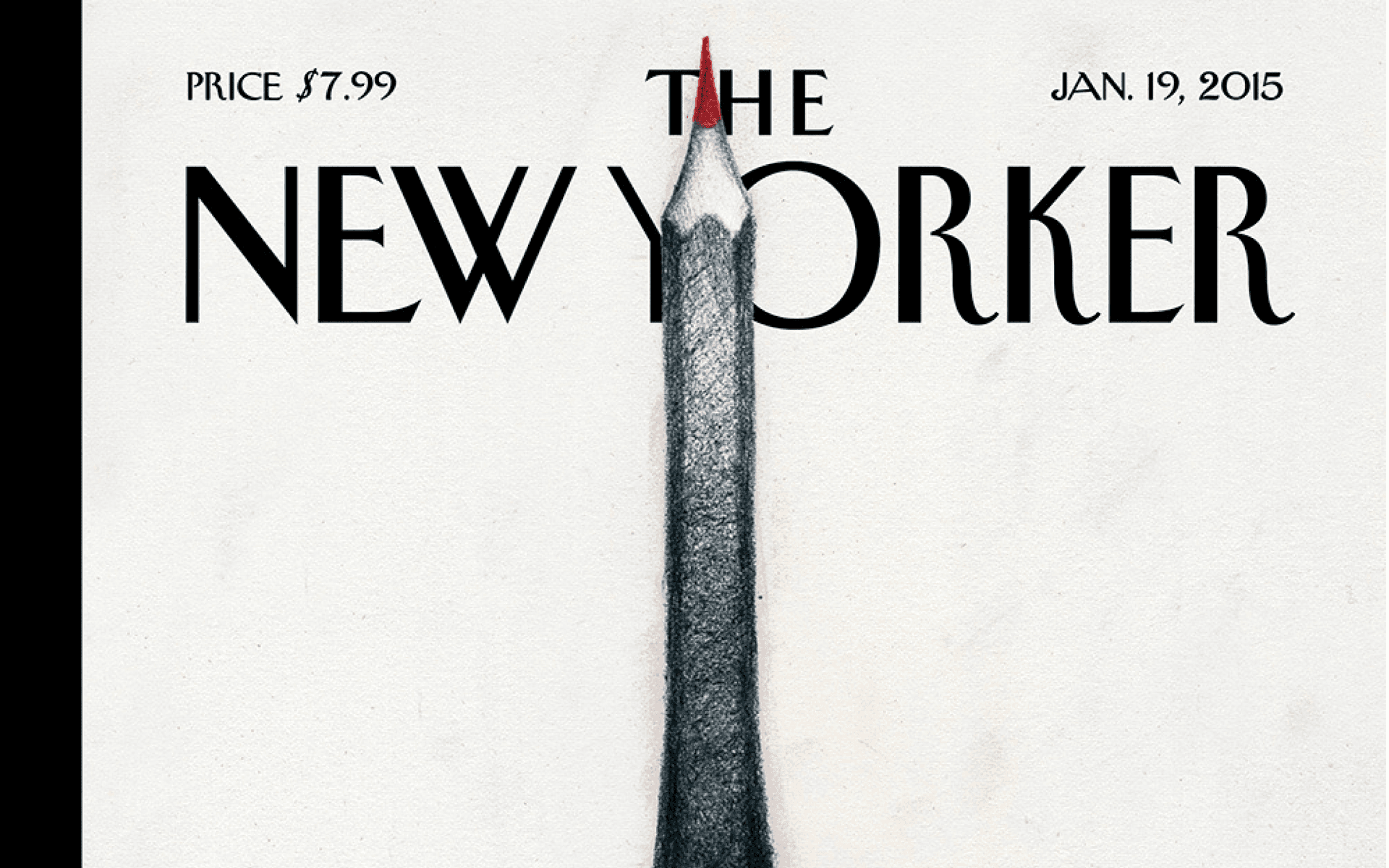

The January 19th, 2015 New Yorker cover designed by Ana Juan to pay tribute to the victims of the Charlie Hebdo attacks.

Francoise Mouly's entire life has been about images and how people respond to them and on this one-year anniversary of the murders at the office of Charlie Hebdo in Paris, The New Yorker art editor is still incredulous that it happened.

"I'm trying to recapture the visceral reactions that I think I felt and everybody felt at the idea of cartoonists being murdered for having a drawn a picture."

At the time, many French people shared Mouly's revulsion. "Everybody went out in the streets and felt unified in a denunciation of the murders." Then came the second-guessing.

"People pointed out that everybody was out in the street but maybe not too many of Arab descent, that it was not truly unified, that it didn't represent every group and every social class." Mouly agrees with the observations but says there was a shared sense of revulson at the thought of an attack on cartoonists, on journalists, on people whose raison d'être is creativity, even mocking. "[Charlie Hebdo] was mocking not so much religion, but the use of religion for political ends."

Mouly worries that because of the cartoons that provoked last year's attacks, the legacy of Charlie Hebdo has been tarnished, that it's viewed as childish, crude and needlessly provocative. "There's been a lot of debates and controversies about the legacy of Charlie Hebdo. It wasn't at the forefront. It wasn't known internationally. Now it is, for all the wrong reasons."

Francoise Mouly came of age in Paris in 1968 when student protesters and eventually many workers nearly brought France's government to its knees. Charlie Hebdo played a key role in those heady days. "They were taking on de Gaulle and the political system at the time as well as the clergy," says Mouly, "and the fact that something from that counterculture movement is still alive, it's important that it leaves a positive legacy."

She also wants people to remember the courage of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists who were killed last year. "I'd like it to be acknowledged for the courage that those cartoonists had in going to an editorial meeting even though they'd received death threats. In this day and age you can always fax things and email and to actually get together in a room and discuss ideas is something worth celebrating."

Mouly deals with hundreds of cartoonists in France, the United States and around the globe. She says many cartoonists feel recommitted to their calling by seeing the importance given to cartoonists in this attack.

"It's tragic way to find out how much cartoons matter. But yes, I think they feel they're at the avant garde of having to keep this freedom of mocking."