Author Margaret Atwood

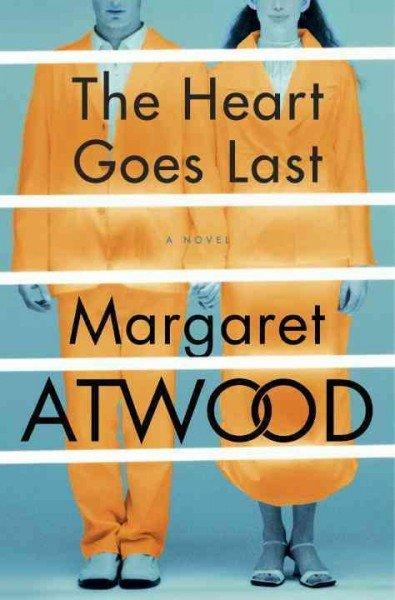

Margaret Atwood's latest novel is set some time in our post-apocalyptic future. But, it turns out, that future might not be that far off.

"The Heart Goes Last" tells the story of couple Stan and Charmaine who give up their freedom for security in the planned community of Consilience — subjects of the Positron Project. Inside Consilience they live for one month in a normal home with normal jobs; and the next month they serve time in the Positron private prison, trading places with another couple that move into their normal home.

Atwood took umbrage at the word apocalyptic when describing the novel.

“[It’s] not apocalyptic, just financial meltdown — like the one we just had,” she says.

The beginnings of the novel are uncomfortably reminiscent of the 2008 financial crisis. Stan loses his job. He Charmaine are forced to leave their foreclosed house and live in their car. The only job that Charmaine can find is a shift at a once fancy night club that has become a de facto brothel.

“I would call it a twisted version of our current reality, which is also in itself rather twisted,” says Atwood, “Housing shortages for all kinds of people, especially young people, that’s with us now.

For-profit prisons are also a current reality in the United States, Atwood points out. In a particularly chilling passage in the book, Atwood describes her dystopic view of the evolution of the prison system. "Prisons used to be about punishment, and then reform and penitence, and then keeping dangerous offenders inside. Then, for quite a few decades, they were about crowd control — penning up the young, aggressive, marginalized guys to keep them off the streets. And then, when they started to be run as private businesses, they were about the profit margins for the prepackaged jail-meal suppliers and the hired guards and so forth."

But the fiction isn’t far off from the reality she says emphatically. “It is unconstitutional to have slavery and forced labor [in the United States], but not if you’re a convicted criminal. So some of that is going on now,” says Atwood.

Before they sign on to the Positron Project, Stan and Charmaine tour the utopian Consilience. But they have nagging concerns about how it runs. In fact, Stan's brother Connor even warns them that there's something fishy going on here. But, in the end it's the luxury of clean bath towels that clinches the deal.

“You know when you don’t have a good set of bath towels, [Consilience] could be pretty darn appealing,” quips Atwood.

But it’s not really a good set of bath towels that coaxes Stan and Charmaine to trade their freedom for security. It's fear, says Atwood.

“When people are really, really scared, they will trade what we fondly think of as civil liberties and freedom. They will trade aspects of that for being told that they are protected and safe,” says Atwood.

Lately there has been a surge of dystopic literature, according to Atwood.

“[Dystopic fiction] comes in waves. In the literary landscape, I would say with The Handmaid’s Tale in 1995, nobody was really doing it at that time. They had in the ‘30s and ‘40s, so we had Brave New World and George Orwell,” says Atwood. “In the 19th century it was all utopias. It was all wonderful versions of the future, because that’s what they believed. They believed that things were going to get better and better. “

In the 1930s and ‘40s the dystopia was the present state of affairs and the utopia was in the future.

“But after the first world war, the second world war, Hitler, Mao, Pol Pot, etc., we have trouble believing in utopias,” says Atwood.

Today's current view of a dystopic future is a product of people’s uncertainty about the future — especially amongst young people, says Atwood.

“[Young people] are writing and reading a lot of fictions like that. Some are just beleaguered fantasias such as the Hunger Games, but other are climate-based fictions. People are worried, quite rightly so, about a changing planet and also a changing and unstable financial landscape,” says Atwood.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?