What modern builders could learn from the Pantheon — and grass bridges in Peru

The Pantheon in Rome, Italy.

You’re in Rome, and your footsteps echo throughout an ancient, marbled structure. You look up, and above the columns, above the walls, there’s an opening to the sky. That opening has been letting in light, rain and snow for almost 2,000 years.

That building is the Pantheon, one of the greatest architectural treasures of the ancient world, and not coincidentally, John Ochsendorf’s favorite building.

Ochsendorf, a professor of architecture at MIT and MacArthur fellow, believes that today’s engineers and architects have a lot to learn from structures like the Pantheon.

With our current focus on exponential progress and the ever-increasing pace of technological change, it might seem strange to be inspired by such retro structures. But Ochsendorf thinks that old buildings have lessons to teach us.

1. Build for the Climate

Climate change will likely be one of the the defining issues of the 21st century, but according to Ochsendorf, the buildings we construct today tend to ignore that.

“In many climates around the world, architecture developed specifically to its climate. And today, energy’s relatively cheap, we can air condition our way out of any heat, so we build glass boxes in the desert and in almost any climate in the world. And that’s not very smart.”

Ochsendorf wants builders to respond to the natural environment by thinking about sunlight, prevailing winds, and climate. Instead of just creating aesthetically pleasing skyscrapers, he urges builders to consider energy use, and come up with ways to minimize it. For example, many classical Indian structures have a ‘Jaali,’ a thin screen that diffuses sunlight and cools the building. Local materials and techniques could have an advantage, argues Ochsendorf. After all, native builders have been responding to their area's climate for thousands of years.

2. Build to Last

There is a maintenance crisis in the US. Roads and bridges that were built 50 years ago are crumbling, and we’re not doing all that much about it. On the other hand, many Roman roads are still standing today, even after thousands of years of wear and tear.

Ochsendorf maintains that we do have the technological capability to create structures that will withstand the test of time. After all, we know the materials that won’t corrode or rust (stone over steel and ancient concrete over reinforced concrete). But in today's world, people build buildings to make money, and it’s cheaper in the short term to construct structures that will only last a few decades. In the long term, however, Ochsendorf feels we’re missing the bigger picture; though our buildings might not last, “the resources we marshall, steel, and glass, and concrete, to build a building for a couple decades, are absolutely immense.”

Instead, he argues that we should take a page from our ancestors and think about the entire life of a building:

“Most buildings in the US are torn down after 45 years… so when we design buildings we must think of how they’ll adapt and change over time. That might mean that a building that’s set up as an office building should have the ability to become mixed use or switch to residential if the market demands it.”

Consider the Colosseum in Rome. It was intended as a sports stadium, but over the years it’s been used as housing, a workshop, a fortress, and a Christian shrine. One structure, but many uses. So as cities adapt and evolve, Ochsendorf believes buildings should do the same.

3. Build for the Community

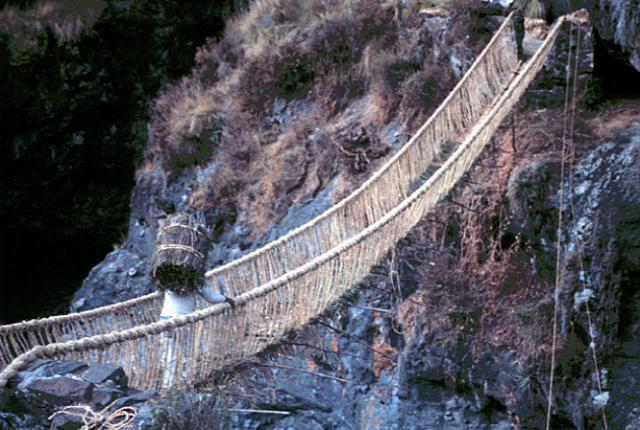

The Inca Empire created many architectural marvels, Machu Picchu being the most famous. But perhaps their greatest achievement, in Ochsendorf’s opinion, were the grass bridges:

“One bridge, in what is now Peru, has been continually used for over 600 years. The bridge is even more extraordinary because it’s made of grass. Now, how could grass last for 600 years? The answer is, it couldn’t, but the importance of the bridge in the community lasts, so every single year the community has a three-day festival and they rebuild the bridge entirely out of grass.”

Ochesndorf views this as a shining example of how intertwined people and the things they build can really be. If a community is invested in a structure so fully that they’re excited about maintaining it, the structure is a vital part of that community.

This dynamic could be especially useful given the current trend of urbanization. Ochsendorfpoints out that we should be ready for growing populations to present incredible challenges around the world.

“We’re building the equivalent of a new Chicago every week for the next 20 years. When you think about the resources, the steel and concrete and glass, required, and then you think of the energy required to heat and cool these cities, we’re looking at half of all greenhouse emissions and energy consumption on the planet. We simply can’t afford to do things the same way we did in the 20th Century.”

But by learning lessons from history, taking a longer view of things, and responding to our natural environment, Ochsendorf believes our cities and structures can be built in a more constructive way.

“It’s a huge challenge, but we don’t really have a choice, we really have to do better.”

A version of this story first aired as an interview on PRI's Innovation Hub.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!