After the A-bomb survivors die, who will be Hiroshima’s memory keepers?

Masaaki Murakami, a volunteer guide at Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Park, listens to 87-year-old atomic bomb survivor Noriho Azuma.

On a recent afternoon in Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park, two men sat on a bench, deep in conversation.

The older one sports a narrow-brimmed fedora. He’s probably in his 80s. The younger guy, in a hoodie, looks like he’s barely out of college.

“It’s so beautiful here,” the younger guy says. “So hard to imagine what it must have been like.”

The old man tells him this used to be a bustling part of town: bars, restaurants, a red-light district nearby. Virtually all that’s left from those times is a ruined building that’s now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome. Before 1945, it was an exhibition hall. The two men are sitting right next to it.

“My father used to work here,” says the old guy. “When I was little, I would play inside the building. I’d slide down the bannister”

We ask the survivor, Noriho Azuma, the question you always ask: Where were you when the bomb exploded?

“I was 17 and should have been at school,” Azuma says. “But school had been cancelled. We’d been ordered to work in a factory.” The factory walls protected him from the blast. The rest of his family also survived.

“I don’t have radiation sickness, he says. “For some reason, my health wasn’t affected. All the same, it would have been much better if I had died back then. Life has been hard. My friends all died young.”

Did the atomic bomb end World War II?

Azuma turns back to his conversation with the young guide.

“Some people blame the United States for dropping the bomb,” he tells the guide. “But I think if the Americans hadn’t dropped the bomb it might have been even crueller. The Japanese government was calling on everyone to fight — even women and children — if the Americans invaded. To fight with home-made bamboo swords! Can you imagine?

“Maybe dropping the bomb was immoral, but we did surrender after that.”

The younger man doesn’t agree. “Take a look at history,” he says. “The war didn’t end because of the atomic bomb.”

It’s a brief moment of discord. Mainly, these two are full of admiration for each other.

“When I came here today, I saw this young guy,” Azuma says, pointing at his new friend. “I saw this guide, talking so knowledgably to visitors. So I approached him and told him he was doing a great job.”

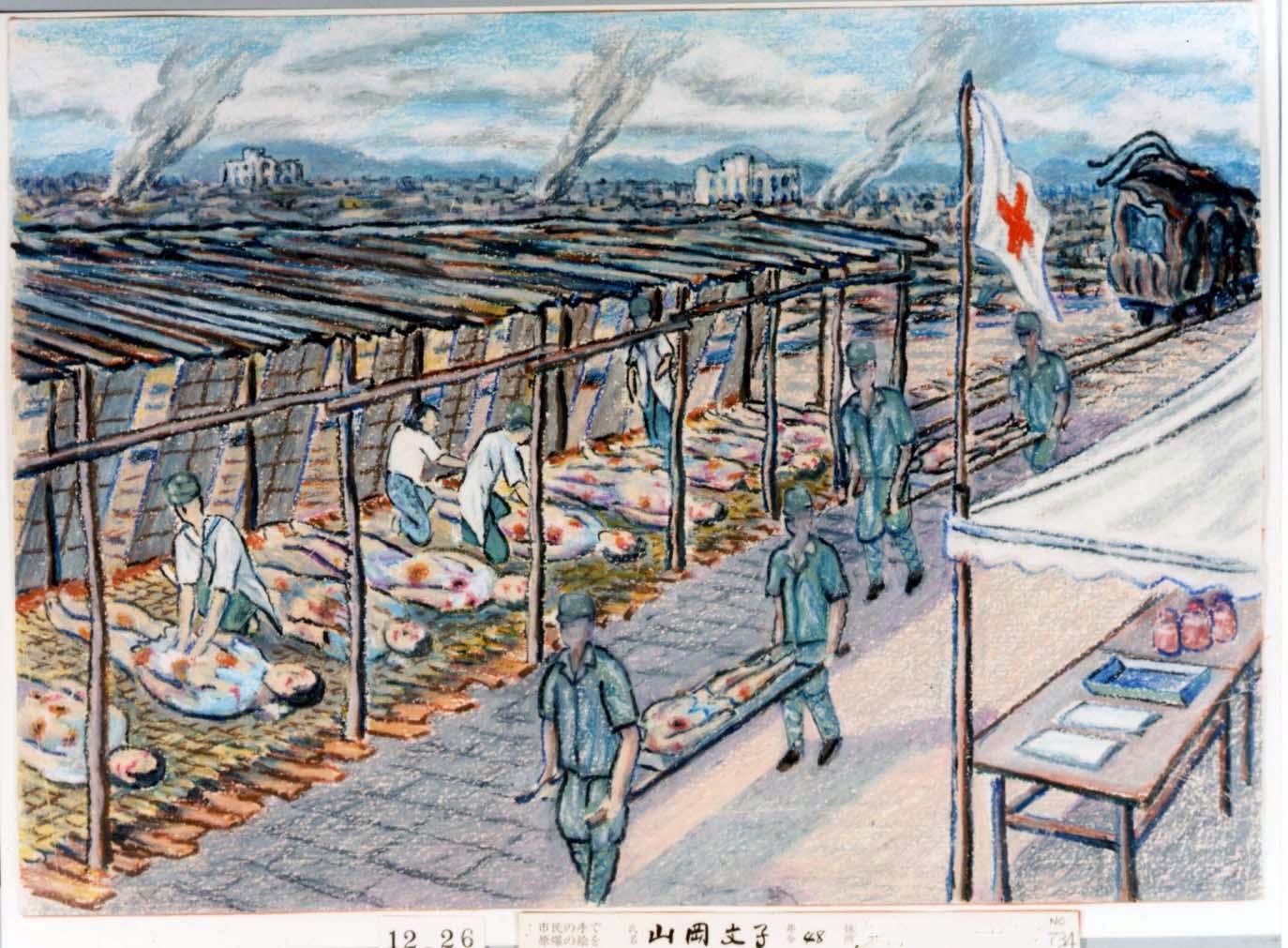

A survivor's drawing

The young guide is named Masaaki Murakami. He's 22. When he first became a guide, he says he just showed people around without explaining much; he was doing it to improve his English skills. But then an older guide he knew started educating him. She showed him sketches of Hiroshima in the wake of the blast, drawn by atomic bomb survivors.

One of the sketches depicted several fires burning across a ruined cityscape.

“I thought it was buildings on fire,” says Murakami. “But the older guide explained to me that it was bodies being burned — huge piles of bodies.

“That really shocked me. I realize I’d never before thought about war seriously.”

Just as Murakami is telling me this, he spots the very woman he’s been talking about, the older guide. She’s in her 50s, pushing a bike through the park. She walks over to us.

Murakami explains that he was just telling us about the sketch she had showed him. She can’t remember which one it is — or that it was such a revelation for him to see it — but eventually, they figure it out.

The woman, Michiko Yamaoka, pulls out a folder. It has more sketches by survivors. Some photos too, which she shows me: one of her mother, who survived the bombing; another of her mother’s sister, who did not.

Yamaoka is so devoted to telling her mother’s survivor story that she has learned English. “It’s very important to speak English because many tourists come to here,” she says.

I ask Yamaoka about the next generation. Do her two children share her fervor?

“My children are very busy,” she says. “They cannot talk about my mother’s story. It’s very sad for me.”

Interactive: The Atomic Bomb Dome, or Genbaku Dome, was the only surviving structure at ground zero. It has been preserved as a peace memorial and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996.

Anxiety over Hiroshima's legacy

This is a widespread problem. The younger generation, even within survivor families, are often distracted with daily life. And so Hiroshima’s team of volunteer guides is graying. That’s why Yamaoka and Azuma, the survivor, are so excited by the eagerness of this young guide in his early 20s.

Murakami doesn’t even have any family connection to the atomic bomb. He is from a neighboring prefecture. But he’s interested.

Before they part, Azuma tells Murakami, he wishes there were more young guides. Murakami agrees. “Young people just can’t relate to the story of the A-bomb,” he says. “Most guides are retirees. Who’s going to do the job when they get too old?”

Who indeed? Azuma says it’s impossible for anyone who didn’t directly experience the blast and its aftermath to truly understand what happened. But, he adds, the next generation should still try to somehow channel the memory of hibakusha.

“It’s a good thing you haven’t had to go through such an ordeal,” he tells the young guide.

And with that, they go their separate ways.

Our series of reports Hiroshima Generations is supported by the United States-Japan Foundation