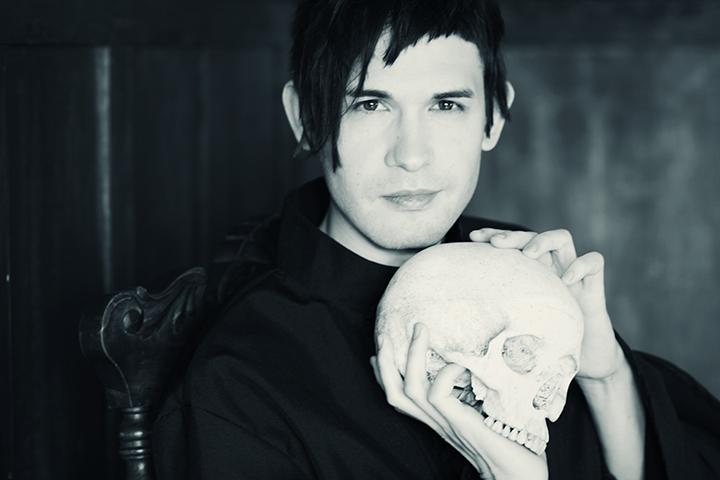

Kazakh glam-rock and opera singer Timur Bekbosunov first got discovered singing Over the Rainbow at at festival in Kansas.

The story of how Timur Bekbosunov became a glam-rock opera singer in the US actually begins in 1958, in Almaty, Kazakhstan, then part of the Soviet Union. Timur says his father developed a strange idea — he wanted to go the US “to see what it’s all about.”

His dad even wrote a letter to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to see if the Communist Party would send him to the US.

He never heard back, but he never forgot America. In 1996 when Timur was 15, his dad surprised him, saying he’d applied to a program in the US on Timur’s behalf and that Timur had been accepted to study English for one year.

He ended up in Kansas, living with a nurse who became his adopted American mother. He says she encouraged him, “as corny as it sounds, to follow [my] dreams. And so I started to sing.”

That’s how Timur ended up being discovered singing “Over the Rainbow” at a festival in Kansas, by a scout from Wichita State University. And that’s where Timur discovered opera.

“I really began to enter this really strange, beautiful world of sometimes abstract, and sometimes ephemeral, way of singing,” he says. “It’s kind of an out-of-body experience when you sing.”

Since then, Timur has performed all over the world — at the Hollywood Bowl, with the LA Philharmonic — and in Kazakhstan. He went back as the soloist and producer of his own opera, The Silent Steppe Cantata, with music composed by Anne LeBaron.

“The music is composed for Kazakhstan folk instruments, so there are no western instruments,” he says. “That makes it a very, very unusual sound.”

The thing is, the people playing all those Kazakh instruments — none of them was from Kazakhstan. The large ensemble Timur brought with him was mostly made up of Westerners, which led to some friction. One time, the director of a hall burst in and interrupted their rehearsal.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DshwPIwEdlzM

“[He said], ‘No, no! It’s all over. You don’t have permission to be here.’ There were people with television cameras there, and he just makes this big stink about the whole thing. And he said we were plotting to shoot Borat 2.”

I’m just glad I wasn’t the first one to bring up Borat, the 2006 film that Kazakhstan once banned and officials denounced as “humiliating.”

But the country’s actually mellowed out on Borat considerably, Timur tells me.

“They aired at first some beautiful imagery of golden eagles flying over the steppes to counteract what Borat was bringing, but eventually they realized: Why are we trying to fight it? Let’s embrace it. And so they did.”

A couple of years ago, the foreign ministry even officially thanked Sacha Baron Cohen for boosting tourism.

And that director who burst into the hall ended up embracing Timur and his crew too — Silent Steppe Cantata toured successfully throughout Kazakhstan.

Back in the US, Timur continued to move into musical genres that defy classification. Take his band, Timur and the Dime Museum:

Listen to TImur and the Dime Museum's "The Hour of the One and Only."

“What we’re doing now could be described as protopunk and minimalist chamber pop at times and it has this really great rock-opera segment to it,” Timur says.

The glammier influences of the Russian, American and European pop music he grew up listening to can also be heard on their forthcoming album, The Collapse.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DuxSHEcZhtiU

Fun, right? Except the album is supposed to be a dark requiem about man-made ecological disasters.

“I would describe Collapse as a ride to the end of the world with a glass of champagne, if you can say that,” Timur says.

You can take that ride in Brooklyn this fall, where Timur and his band will perform The Collapse at BAM’s Next Wave Festival.

The other big project Timur is focusing on? His dad.

Oddly, their roles have now reversed; Timur wants his dad to join him in Los Angeles. But after spending his whole life in Kazakhstan, his father has mixed feelings about leaving.

“I’m trying to convince him that this is a good country to be in,” Timur says.

Timur’s adopted American mother passed away last month — and his mom died last year.

“I always felt I was the luckiest person because I had two mothers — one in Kazakhstan and one the United States. And suddenly I only have my Dad. I told him he has to step up his game,” he says, laughing. “When he gets to … the United States, I’m going to smother him with love.”

Sounds like his dad’s letter to Khrushchev is finally being answered — 50 years later.