Karla Monnaco teaches bilingual third graders at Giddings Elementary. With a shortage of bilingual teachers, the school recruited her at a job fair in Monterrey, Mexico.

Sergio Gon sits in the corner of his kindergarten classroom in Giddings, Texas, reading a book to his students entirely in Spanish. He’s a bilingual teacher at the elementary school there, a town of about 5,000 people halfway between Austin and Houston. Most of his students don’t speak English.

Down the hall, Karla Monnaco, also a bilingual teacher, teaches third grade in another classroom. By the time Gon’s students reach Monnaco’s class, they’re expected to speak both English and Spanish.

“What you want as a bilingual teacher is to fill those gaps that they have and fill it so they can feel like they fit and they are successful,” says Monnaco.

In Texas, like much of the United States, if a school district has 20 or more English Language Learners, or ELLs, in a single grade, it’s required to offer bilingual education with a certified bilingual teacher. But for more than two decade many school districts in Texas haven’t been able to make that happen. Last year, more than half the school districts in Texas couldn’t find enough bilingual teachers to teach all the students learning English — as required. They have to ask the state education commissioner to waive that requirement for the year.

“That’s really difficult, hiring bilingual teachers,” says Shane Holman, assistant superintendent at the Giddings Independent School District. “We have a large migration of Hispanic population at the same time as white families are having less children."

Some schools districts, like Giddings, are tackling the gap by looking beyond the US for qualified teachers. That’s how Monnaco and Gon were hired seven years ago from Monterrey, Mexico, just south of the Texas border. They met Giddings school administrators at a job fair, had an interview, and moved to Giddings with their two daughters. Yes, Monnaco and Gon are married.

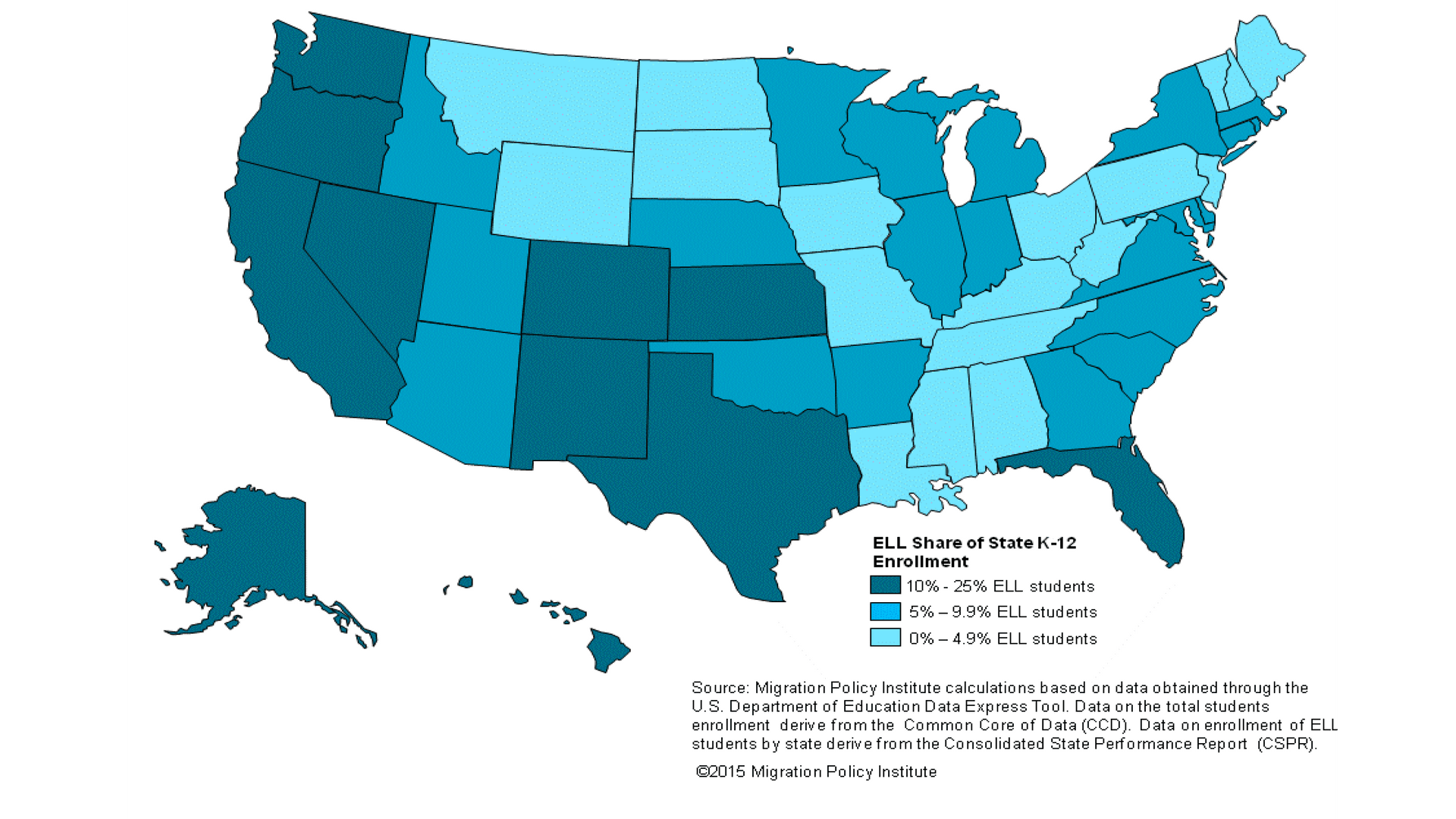

Overall in the US, the number of English Language Learner students doubled from five percent in 1990 to more than ten percent last year.

But the shortage of certified teachers continues to drag on in Texas — and nationally, too.

“We haven’t taken the time or the initiative or necessary action to recruit, to retain, to incentivize, to promote, to train bilingual teachers,” says Santiago Wood, executive director of the National Association for Bilingual Education. “It has to be a focused effort. It cannot be just business as usual.”

Wood says he remembers recruiting teachers from Mexico and Spain in the late 1980s when he was a school superintendent in California. He says not all school districts are making it a goal to fill those positions. “School districts that make this a priority are the ones that are not having problem recruiting bilingual teachers because they had the courage … to take the right steps,” Wood says.

Other Texas school districts, especially around Houston, have recruited teachers from other countries for nearly a decade. Now, they mostly recruit from Puerto Rico.

In Giddings, about half a dozen teachers recruited from Mexico are still teaching there. Back in Gon’s kindergarten classroom, he finishes up story time, and reminds his students of why they’re all there: “Todos estamos aprendiendo hablar inglés,” he says. Then, he translates: “Everybody can learn how to speak in English. Muy bien.”

When they started teaching, Monacco and Gon lived in the US on temporary visas sponsored by the school district. Last year, they received their green cards, and plan for US citizenship next. They don’t have plans to move back to Mexico.

Share your thoughts and ideas on Facebook at our Global Nation Exchange, on Twitter @globalnation, or contact us here.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!