Students in Brian Gray and Mark Giuliucii's class don't get letter grades or take multiple choice tests.

At Sanborn High School, Mark Giuliucii’s freshman history class is wrapping up its unit on the French Revolution, but not with an ordinary test.

Instead, students are writing an obituary for a character they’ve pretended to be throughout the entire unit. “They are demonstrating to us that they have mastered the content by killing off their character,” says Giuliucii as he stands in front of the large, loud classroom.

The assignment allows students to analyze the events they’ve studied through a creative lens, rather than just memorize names and dates. “If you’ve ever given a multiple choice test, you know that if you give it two days later they’re going to have forgotten the information, because students have become adept at memorizing things for the moment,” explains Giuliucii, who hasn’t given a multiple choice test in years.

At this small high school in New Hampshire, there are no letter grades, and students can take a test as often as they want. Administrators here are taking a risk and preparing their students for what they hope will be the future of education.

The ultimate goal of the obituary assignment is for these students to know that there’s more to the French Revolution – human motivations, political tensions – lessons that can still apply today.

“So when we see something happening in a different part of the world we can say, ‘Oh I see similarities, I see differences. I can predict what’s going to happen,’” says Giuliucii.

Giuliucii and his co-teacher, Brian Gray, are doing more than just good teaching. It’s a learning style called competency based education.

A Different Way to Grade

At Sanborn, students’ learning is measured through real-world projects done on a flexible schedule. Instead of letter grades at the end of a semester, teachers make a point of giving specific feedback throughout.

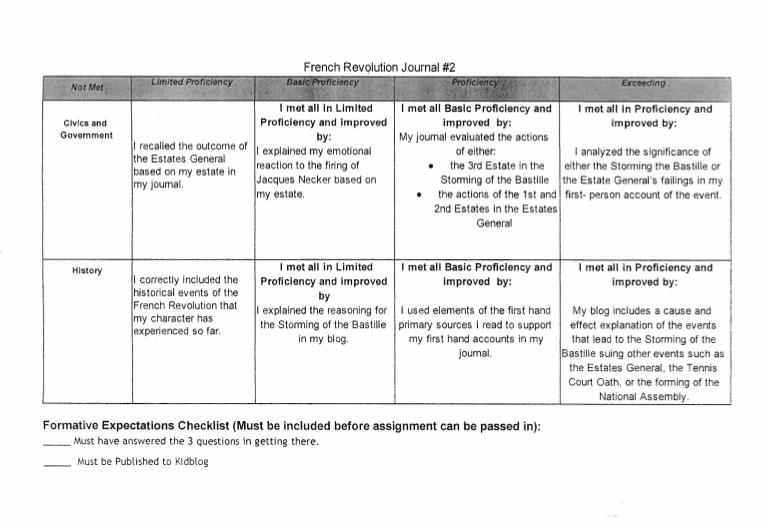

One clear example of this change is in Sanborn’s report cards. Each class at Sanborn has a list of core competencies, skills that students are expected to master in order to pass the class. Instead of a letter grade for the subject, students are labeled as proficient or not, in each skill.

It doesn’t matter if students aren’t able to prove mastery right away. The have until the end of the school year to retake assignments and improve their overall scores.

Ann Hadwen, a Vice Principal at Sanborn, says the system is meant to mirror the working world.

“The world that we live in, you have to do things, you have to perform,” Hadwen says. “It’s not a paper and pencil test that you’re trying to gain 100 points to say that you passed.”

Ahead of the Curve

Seven years ago, Sanborn was a mediocre school district surrounded by high-performing ones. To turn things around, the entire school community decided to take a risk and transform teaching and learning.

The state of New Hampshire was already encouraging school districts to take a look at competency-based education, so Sanborn became an early adopter of the model – diving in headfirst.

Today, Sanborn Regional School District is one of only a few public school districts that has completely converted.

“People want to come here all the time,” says Vice Principal Hadwen. “They're constantly sending us emails and asking ‘Can we come visit and bring a team and find out what you're doing?’”

Educators around the country are taking notice as the model picks up steam: Colorado, Georgia, Oregon, Maine and other states are all starting to experiment with competency-based education in their own public schools.

The model is also taking off in higher education. University of Michigan, Purdue University and University of Wisconsin all offer competency-based degrees. And not too far from Sanborn, Southern New Hampshire University has become a national leader in online competency-based programs.

After Graduation

Despite the rise of competency-based education, most undergraduate programs in the U.S. still continue to teach and test traditionally. That’s something that worries Sanborn senior Amanda Moulaison.

Moulaison is going to Worcester Polytechnic Institute in fall, and she says she’s worried about how prepared she’ll be for a school where there won’t be second chances.

“It’s really not applicable to the next four years of my life,” says Moulaison.

Principal Brian Stack has been with the district since the beginning of this experiment more than six years ago. He’s proud of what they have accomplished. More students than ever before are getting into competitive regional schools like Boston University and Northeastern.

Stack says its partially because the system encourages students to always try to do better – a skill that extends beyond the next four years.

“I want every single one of our students to go to college with that mindset. Every paper they have to write, every test they have to take, every project they have to work on, when they get into the workplace — everything they have to do,” Stack says. “Constantly be trying to improve.”

And, Stack says, that will make Sanborn students successful anywhere — even if they won’t be able to retake that first test freshman year.

This story was produced by On Campus, a public radio reporting initiative focused on higher education produced in Boston at WGBH.