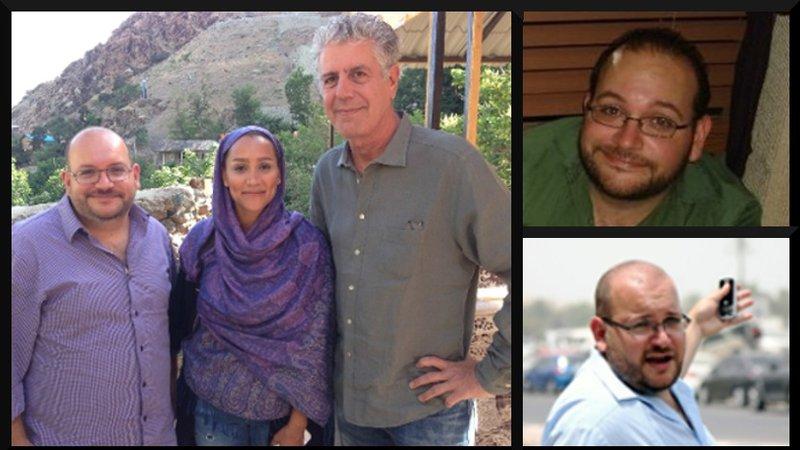

Washington Post correspondent Jason Rezaian with his wife and with food writer Anthony Bourdain, with whom the Rezaians collaborated on an episode of Bourdain's CNN series.

EDITOR'S NOTE: On Saturday, Washington Post correspondent Jason Rezaian was freed from an Iranian prison after 18 months in captivity.)

The last time I saw my friend, the Washington Post Iran correspondent Jason Rezaian, we were sitting at a café in San Francisco, a few blocks away from the Bay Bridge. It was 2012 and he was with his wife, the Iranian journalist Yeganeh Salehi, who I tutored in my writing class at the San Francisco Writers’ Grotto. I shared stories about my 1998 visit to the picturesque city of Esfahan, a city so beautiful Iranians call it nisf-e-jahan, Farsi for half the world.

I liked that place, I told them, but whoever made that comment had clearly never visited San Francisco.

Jason laughed. Then he tried to convince his wife, who seemed repulsed by my comment, that I did not hate Iran.

“No, no,” I explained, “I actually love Iran.”

She looked confused: Why does this Indian American from California love Iran? Jason looked around the room and leaned closer. “Bro, I don’t think you should admit that these days,” he whispered.

When we met, Jason had just been offered the position at the Post. I spent four years covering the Middle East for Amnesty International in Washington and I suggested possible human rights related stories for Jason to cover.

He had other ideas. “I know about those stories and they are important but I also want to show everyday Iranian life,” he said. He became animated when he described wanting to write a piece about Tehran residents who love the Los Angeles Dodgers.

As a San Francisco Giants fan, I said it was a lousy idea, but I understood his point: Jason saw his new position as a chance to add texture and complexity to how Americans understand Iran. It was also a way to challenge the misperceptions that we both heard growing up.

Jason and I are the same age, in our late 30s, and we grew up in California in the 1980s at the height of the power — and abuses — of the late Ayatollah Khomeini. It was not uncommon for kids back then to call people with names like Rezaian or Janmohamed “camel jockeys” and “Khomeini lovers.” We both had our own way of coping: I would tell bullies that my parents are actually Indian from Tanzania and Jason would explain that Khomeini was not in fact his relative. It never really worked.

As we reached college, the insults morphed into more elegant, eloquent racism but the scars remained and it left us both with a shared desire to study and to visit the Middle East. I spent a year backpacking through the region from 1998 to 1999 and I was particularly moved by my trips to Iran.

My parents are devout Shia Muslims and I received a pilgrimage visa to visit the holy shrines in the Iranian cities of Qum and Mashhad. I also ventured across the country, meeting shop keepers who invariably wanted me to explain just what was this new thing Americans were calling “hip hop.” I felt so at ease with my new found friends that I returned to Iran a few months later with a group of fellow UC Berkeley graduates.

In many people’s minds, Iran is a place full of black clad, chest beating people who think only about how repressive their government is. I did see that Iran too—a professor I met in Mashhad, for example, asked if I would smuggle out his books of poetry for his nephew in Seattle. But I also met people who preferred the present government to the Shah’s brutal rule, who challenged me to weed out the pitying tone that Americans, myself including, often use when describing their country.

I also found a country that was not as isolated as I imagined — for example, I watched “Titanic” more times than I care to recall and I was stopped on the street several times by people wishing to offer me condolences for the Columbine, Colorado school shooting, which happened during my visit Tehran visit in 1999. I do not know what surprised me more — the outpouring of affection or the fact that so many Iranians follow domestic US news, a contrast to how little Americans know about Iran’s internal politics.

When Jason and I met, this is what we discussed — how do we speak about Iran to Americans? At Amnesty International, I often hosted former political prisoners from Iran who spoke about the humiliating treatment they received at US airports. But so many in Washington ignored this part of their story and only focused on their experiences being tortured in Iran, often using their harrowing tales to justify military strikes on Iran.

This was even more apparent when I worked as a foreign policy aide in the US Congress, where I found it more difficult to speak rationally on Iran than on Palestinian rights. Often my instinct was to avoid criticizing Iran but I knew this was neither correct nor responsible. Jason understood his predicament and what was remarkable about him was that he welcomed this challenge.

The last time we corresponded was in late April 2014. He had just published a piece about how sanctions led to higher prices for basic goods like bread in Iran. It was exactly the type of story he wanted to write, he told me.

Jason never professed his love for Iran and he laughed at me for owning an Iranian soccer jersey. I pointed out the double standard that I also own a Colombian jersey and yet no one assumes I support that country’s appalling human rights record, the same way people do when I wear my Iran shirt. Still Jason knew that flag waving — America’s or Iran’s — was not his duty. But it was clear in his pieces how much he wanted to add depth and empathy to US coverage of Iran and how much he grew to love Iran.

This was a tragedy — and irony — of his unjust, cruel arrest, conviction and imprisonment. Mostly, I miss Jason as friend. We never resolved our debate about which restaurant in San Francisco serves the best tacos. But I also missed him as a reader — his stories added color to a country that America has long demonized.

His detention was not just our loss, but Iran’s, too.

Zahir Janmohamed previously worked as the Advocacy Director for the Middle East and North Africa at Amnesty International and as a senior foreign policy aide to Congressman Keith Ellison of Minnesota. He is currently writing a book about Gujarat, India. More than 540,000 people signed an online petition asking Iran to free Jason Rezaian.