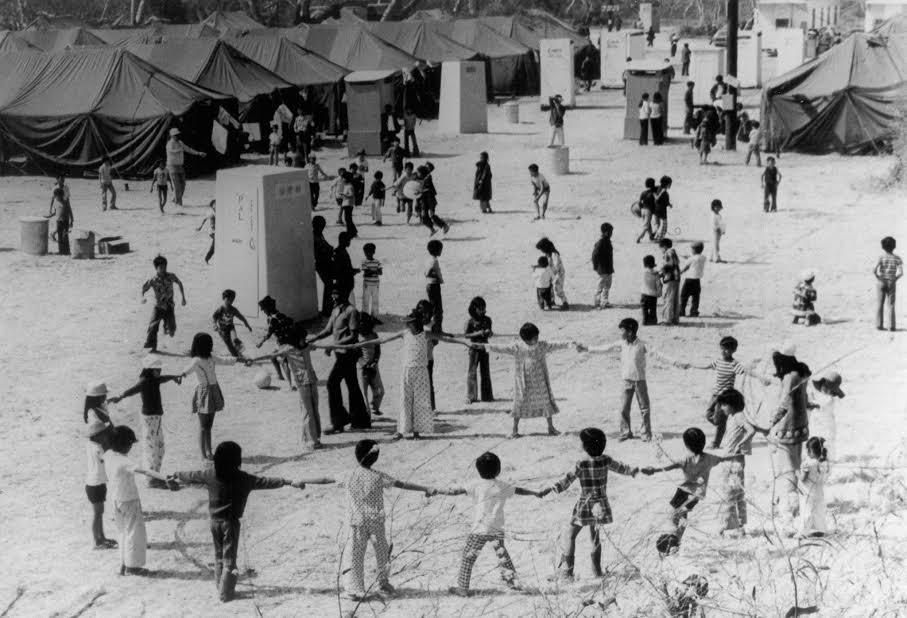

With the help of the military and civilian aid groups, Vietnamese refugees at California's Camp Pendleton created a community after being resettled there in 1975. They received food, shelter and services to help prepare them for permanent residence in the United States.

Forty years ago this month, as North Vietnamese forces were trying to enter the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon, Frances Nguyen was trying to get out.

Just 12 years old at the time, Nguyen and her parents headed to a harbor and managed to get aboard a vessel. "It was so full,” she remembers. “Other people were trying to get on, but they got kicked off. It was very sad to see people trying to swim toward the ship to get on.”

It was one of the last vessels that left before the city fell. The next day, the government of South Vietnam surrendered.

The ship the Nguyens boarded had no destination, but they were about to be helped by a hastily organized rescue effort dubbed “Operation New Life.” It was a massive resettlement program for Vietnamese refugees organized by the US government, and it eventually brought more than 130,000 Vietnamese to America in the immediate aftemath of the war.

See photographs that show how Vietnam has changed over the years.

After arriving at a processing center in Guam, the Nguyens were given the choice of four arrival locations in the United States: California, Florida, Pennsylvania or Arkansas. Not knowing much about the United States, the family let the climate decide.

“We chose California because we heard the United States is very cold,” Nguyen says. “So we chose to go to California, and we ended up in Camp Pendleton.”

Camp Pendleton, a sprawling Marine Corps base in San Diego County, was hastily selected as the West Coast site for temporary Vietnamese refugee camps. The Marines there were used to fighting and dying in Vietnam, but they didn’t know that would also have to help manage the war’s aftermath, says Faye Jonason, Camp Pendleton’s historian.

“This is something they were not expecting,” Jonason says.

The Marines were only given a few days' notice about the plans for the refugee camp. They hastily tried to build the camps from scratch, even going as far away as Utah to get extra tents, but they were overwhelmed by the number of people coming to the base. Jonason says they broadcast an urgent public appeal on the radio, asking for volunteers.

.jpeg&w=1920&q=75)

At its peak in the summer of 1975, the program housed nearly 20,000 Vietnamese in eight different camps around Camp Pendleton. Many of the refugees had left Vietnam so quickly they came with nearly nothing. Ken Nguyen — no relation to Frances Nguyen — remembers owning only one shirt and having absolutely no money when he arrived as a 21-year-old.

He also remembers the announcements and music played over the speakers of the public address system. “The biggest thing was the Beatles song at the time, and also Santana,” Nguyen says “And don’t forget Elvis! Elvis was a big hit back then.”

Frances Nguyen also remembers the camp, where she took her first steps into American life. She had her first English lessons there, and even joined the camp Girl Scout troop. “Being 12 years old, you just kind of accept what’s going on and learn to adapt,” she says.

.jpeg&w=1920&q=75)

The last refugee camp at Camp Pendleton closed in October 1975, and many of the people housed there left to create Vietnamese American communities in places like Orange County, San Jose and Houston.

Ken Nguyen later graduated from Georgetown University and is now a municipal parks commissioner. He recently celebrated his 35th wedding anniversary to a fellow refugee he met at Camp Pendleton.

Frances Nguyen graduated from the University of California, Irvine, and went on to become a successful businesswoman and president of the Chamber of Commerce in Westminster — home to Southern California’s Little Saigon.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

They're both comfortable sharing their experiences as refugees at Camp Pendleton, but Jonason says that not everyone is so open. Pendleton also reminds many people of a lost war and a lost country, she says.

“There are those who don’t want to do anything related to this place,” Jonason says. “They don’t want to look at the pictures. They want to get rid of that part of their life.”

Frances Nguyen says she’s spent the decades since leaving Camp Pendleton embracing this country, but she hasn't forgotten the place she left behind.

“I always tell my kid, 'On one shoulder you have to be Vietnamese, on the other shoulder you have to be American,'” she says. “So how do you balance that? This is a fast lane society. You have to adapt to be an American. But at the same time, you cannot forget where you are coming from.”

It’s a sentiment that many Vietnamese who came to this country four decades ago can understand.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!