Photographer Catherine Karnow captures a changing Vietnam

Although same-sex marriage isn’t legal, Vietnam is at the forefront of gay rights in the region and gay weddings are not uncommon.

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, the prestigious Art Vietnam Gallery in Hanoi is showing “Vietnam: 25 Years of Documenting a Changing Country,” a photo exhibition of National Geographic photographer Catherine Karnow’s lifelong work in that country. In his introduction to the exhibition, Andrew Lam writes that the photographs capture a country that has many versions of itself.

If you want to know what it’s like to wait, take a look at Catherine Karnow’s photo of people at the dock of Saigon in 1990. There’s something so solitary and stoic in their postures as they wait for their ferry that the tableau comes to represent Vietnam itself writ large.

A few years after that picture was taken, change came, and it came roaring. One photo in particular is most telling: men squatting on the ground painting Coca-Cola logos on a dozen signboards that announced the opening of bars, restaurants, and hair salons. Vietnam had just revised its constitution to allow the practice of “private capitalism" and small businesses sprang up seemingly overnight.

In another decade or so those signs will have turned into gigantic billboards that line rivers and boulevards in major cities, telling citizens to buy Tiger Beer, Honda Dream motorcycles, Toyotas, Sony TVs and, if they can afford it, a new condo. So much so that they will have overshadowed old slogans romanticizing laborers and farmers and the virtues of a socialist paradise.

Dramatic, too, was that now famous photo of Phuong Anh Nguyen, a returning Vietnamese American who owns a stylish bar called Q Bar in downtown Ho Chi Minh City. She is wearing dark shades, a bikini top and tight black shorts, sitting astride a vintage Vespa motorcycle holding a live chicken by its neck. In Vietnam the photo sparked controversy when it first appeared in the book Passage to Vietnam. So daring on the streets of Ho Chi Minh City. So bold. LA style. “We know she’s a Viet Kieu [Vietnamese expat] because Vietnamese don’t hold live chickens by their necks but by their legs,” one woman quipped. Soon thereafter, daring young women, like Phuong Anh, would wear bikini tops to go out drinking, and voilà, a fad was born.

Though the country remained under a one-party rule, Vietnam has since the late 1980s eased its once-iron grip on the economy and cultural life, moving from a socialist to a free market economy. Gone are the days when citizens were required to discuss Marxist-Leninist doctrines at weekly neighborhood sessions. Gone too are the permits needed to buy rice from state-run stores, or to move from one city to another.

The drab, impoverished and immobile nation that Catherine saw when she first visited in 1990 quickly shifted under her lens. And fascinated, she kept coming back. After all, unlike Albania, Russia or Italy, or dozens of other exotic locations that the famed National Geographic photographer has visited over the years, Vietnam is deeply personal, and a kind of inheritance.

Her father, Stanley Karnow, who passed away in 2013, was a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and celebrated journalist who spent the bulk of his career covering the Vietnam War. He served first as bureau chief for Time-Life and then as foreign correspondent for The Washington Post. Having witnessed the first American killed in 1959, he watched the war escalate, then end ignominiously: Americans troops withdrawing, South Vietnam abandoned, North Vietnam reigning supreme. He went on to write the masterful Vietnam: A History, an exploration of the root causes of how America ended up in one of its most lamentable overseas ventures. He also served as chief correspondent for the 13-hour series "Vietnam: A Television History" for PBS that won six Emmys and a Peabody award.

There’s a saying in Vietnam: “Cha truyen, con noi,” which can be translated to something along the lines of “Father transmits, child progresses.” It speaks to the Vietnamese understanding of how a legacy—be it a profession, passion or family tradition—can be passed down, as if fated, through the generations. In the Vietnamese sense of progression, since father bore witness to the war in Vietnam, it should only be natural that daughter, too, should bear witness to the country’s emergence from behind the bamboo curtain into the bright light of globalization.

What Catherine’s photos capture is a country that has many versions of itself.

In one version, there’s a nation still bound by the past. General Vo Nguyen Giap, who led the North Vietnamese communist army against the French and the Americans, is greeted with pure joy when he visits Dien Bien Phu 40 years after the French were defeated. The general was in good form as seen in Catherine’s portrait of him back in 1990, but the memories of war were all there, still raw, in his eyes.

The past continues into the future in the form of Agent Orange, dropped along the Ho Chi Minh trail and parts of South Vietnam, where its appalling effects have continued to express themselves in the form of birth defects.

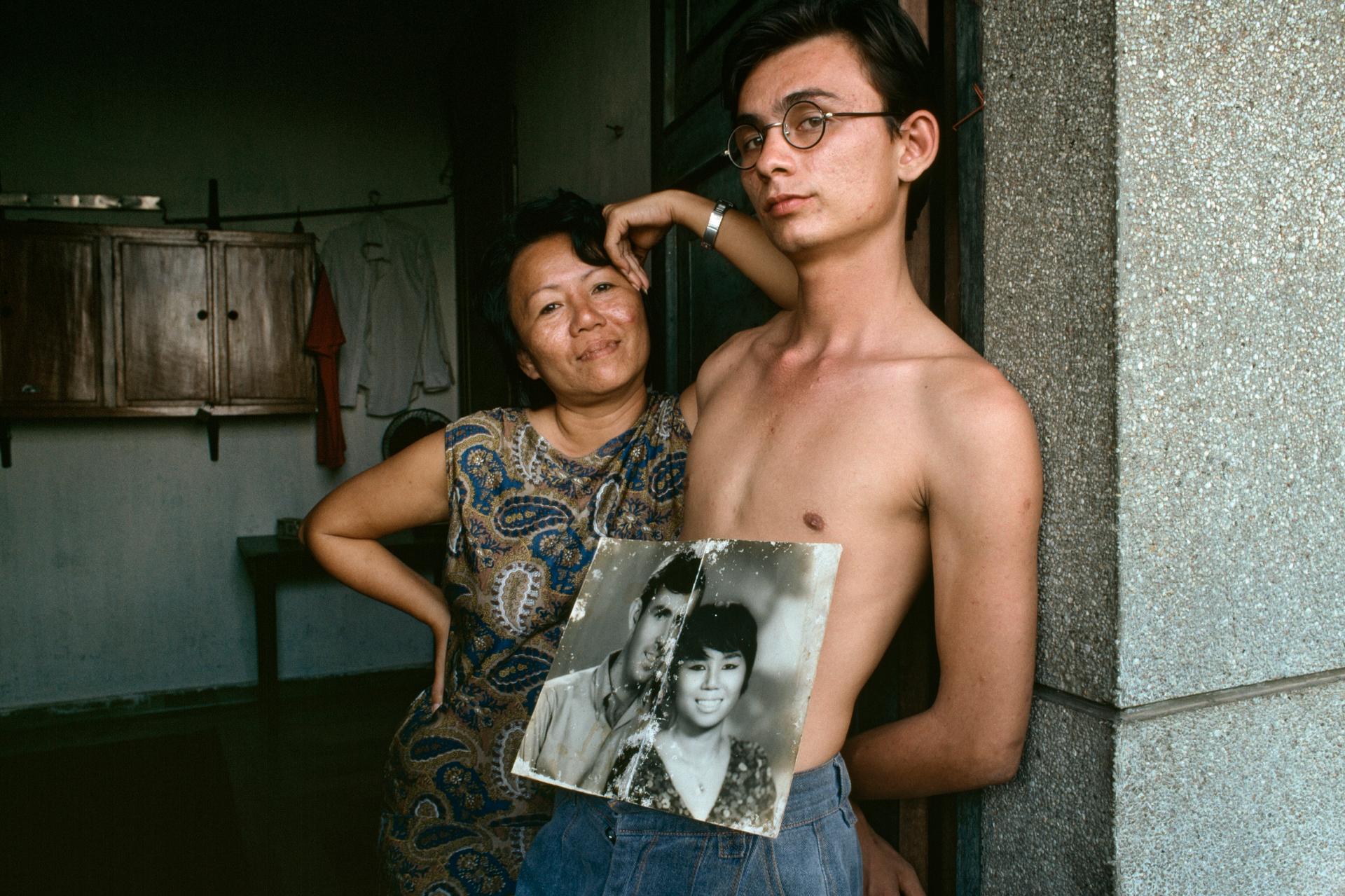

Or take a look at the shirtless, mixed-race young man with a faded black and white photo of his parents: a handsome American GI and his Vietnamese bride. The young man’s expression is both that of resignation and longing. Will his father ever return? Will he and his mother be allowed to emigrate to America? And if he does reach fabled America, will he find his American father?

But there’s another version of Vietnam, a nation freeing itself from war memories and rushing forward. And it’s growing younger and younger. The country’s population, passing 90 million, has more than doubled since the Vietnam War ended. Two out of three Vietnamese have no direct memory of the war. Everyone instead is in the grip of modernity.

Vietnam’s society has become complex, with many different social strata, and increasingly expressive: filmmakers, artists, fashion designers and singers are pushing the cultural envelope daily. It is no wonder that a young gay couple in Catherine’s photo have no qualms hugging each other in a club. Although same-sex marriage isn’t legal, Vietnam is at the forefront of gay rights in the region and gay weddings are not uncommon.

Along with a fledgling civil society, there is a growing middle class, and a slow erosion of the government’s control over people’s lives as pressure rises for reform, transparency and pluralism. The return of Viet Kieus to the homeland, too, is bringing something new: Some bring back financial investments and technological know-how while others, like bar owner Phuong Anh Nguyen and the artist Dinh Q Le, with his woven photographs of layered memories of the U.S. and Vietnam, bring new ways of looking at art and self expression.

But to the discerning eye, there is a widening gap between the haves and have-nots. The land where the super-wealthy play golf was once green rice paddies that belonged to poor farmers, often driven out by powerful developers. A crocodile leather Gucci bag in that new luxury store is worth the price of half a dozen girls in the Mekong Delta, often sold for as little as $400 by their impoverished, debt-ridden farmer parents to traffickers who take them across the border where many end up in brothels.

There's a Vietnam that is moving toward a conspicuous consumerist culture, a new upper class living a grand life with armies of servants waiting on them hand and foot. And there's a Vietnam that remains mired in poverty, one in which many families live hand to mouth. Underneath that gorgeous photo of a gleaming metropolis of Saigon, an army of vendors and laborers are trying to get on the right side of the economic divide.

Vietnam keeps changing and it keeps drawing Catherine back over the years. Her parents are gone now, her family home sold. But if there’s a place where she remains connected to her father (and her mother, who lived in Vietnam in the ‘50s), it is this country where both their careers blossomed.

Stanley Karnow recorded the nightmares of the Vietnam War with words, and Catherine Karnow has, with her photos, managed to chronicle Vietnam’s long night’s journey into day.

Karnow's exhibition runs until May 8th. This story was produced as part of a collaboration between PRI's The World and New America Media.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?