Folorunsho Alakija speaking at the Fashion 4 Development First Ladies Luncheon and Fashion Show in New York. Alakija is thought to be the richest black woman in the world now.

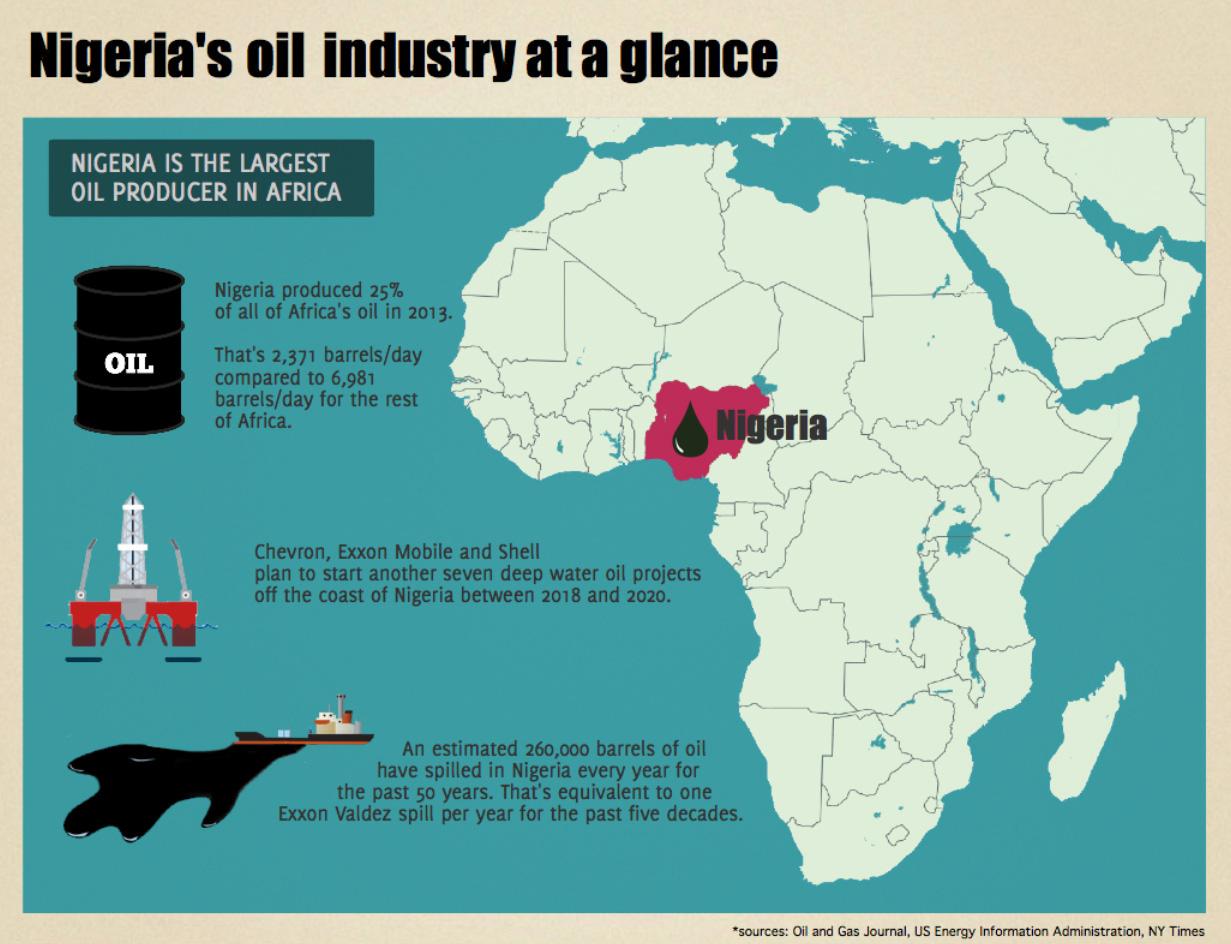

This is a story of how a fashion designer became a billionaire. It also speaks to the lack of transparency in Nigeria’s oil sector, one of the world’s largest.

The billionaire in question is Folorunsho Alakija. These days she travels the world giving motivational speeches. She runs a charity for widows and orphans. And she owns a lot of real estate, including a really nice apartment on Hyde Park in London. But calling this empire ‘self-made’… well, there’s more to the story.

Alakija started out as a secretary in Nigeria’s biggest city, Lagos. Eventually, she went to London for design school, came back to Nigeria, and started her own label called Supreme Stitches. Her clothes were a hit, and soon she was designing for Nigeria’s elite.

By then it was the early 1990s, and Nigeria’s oil industry was booming. The government had mapped out its swamps and seas into a grid of rectangular shaped “blocks,” and Nigerians who were invited could apply for a license to look for oil within a particular block. Alakija decided she wanted in. She met with the oil minister at the time, and eventually she got a block.

“We weren’t sure what was there,” Alakija said in a 2012 interview with CNN’s African Voices, “We were novices in the industry, of course.”

It turned out Alakija’s block was a gusher. It can produce up to 250,000 barrels of oil a day. In December, Time magazine put her worth at $3.3 billion, $300 million more than Oprah Winfrey.

I’ve tried many times over the last few months to reach Alakija or her people for an interview to learn more about her story, but with no response.

In her few media appearances, Alakija attributes her success to luck and hard work, but Olusola Bello, energy editor of BusinessDay Nigeria, says there’s more to her story. He notes that when Alakija was a fashion designer for Nigeria’s elite, one of her clients was Maryam Babangida, wife of the then-president, General Ibrahim Babangida.

Babangida ruled Nigeria from 1985 to 1993. According to Bello, the facts — that Alakija was close to Babangida’s family and that she got an oil block — are not coincidental.

Licenses are granted through connections, Bello says, “It is not by bidding. A lot of people were given concessionary blocks, oil blocks, depending on how close you are to the president.”

For many Nigerians, Alakija represents the cronyism that defines Nigeria’s oil sector. In most countries, if you want an oil block, you face a competitive process: The person with the best business plan and the most experience wins the block. But Musikulu Mojeed of the newspaper Premium Times says it probably didn’t work that way for Alakija.

“It's very simple. That she knew people and you got awarded an oil block. Not much hard work there,” Mojeed says.

In elections at the end of March of this year, the Nigerian people said “enough is enough” to this type of system, voting ineffectual President Goodluck Jonathan out of office. For many voters, the corruption in the oil sector under his administration was a big reason why. Mojeed says with the incoming president Muhammadu Buhari, “there’s a new sheriff in town,” and oil-block policies might be reviewed.

So what does that mean for Folorunsho Alakija? Well, she’ll probably still get to keep her oil block. But Mojeed hopes that Nigerians will start thinking differently about her story. He understands why some consider her a hero for making the right connections.

But he hopes that someday Nigerians can build business empires like Alakija’s without having to know any ministers, or the president.

Julia Simon’s reporting from Nigeria received help from Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.