Think our voting system is colorblind? Think again

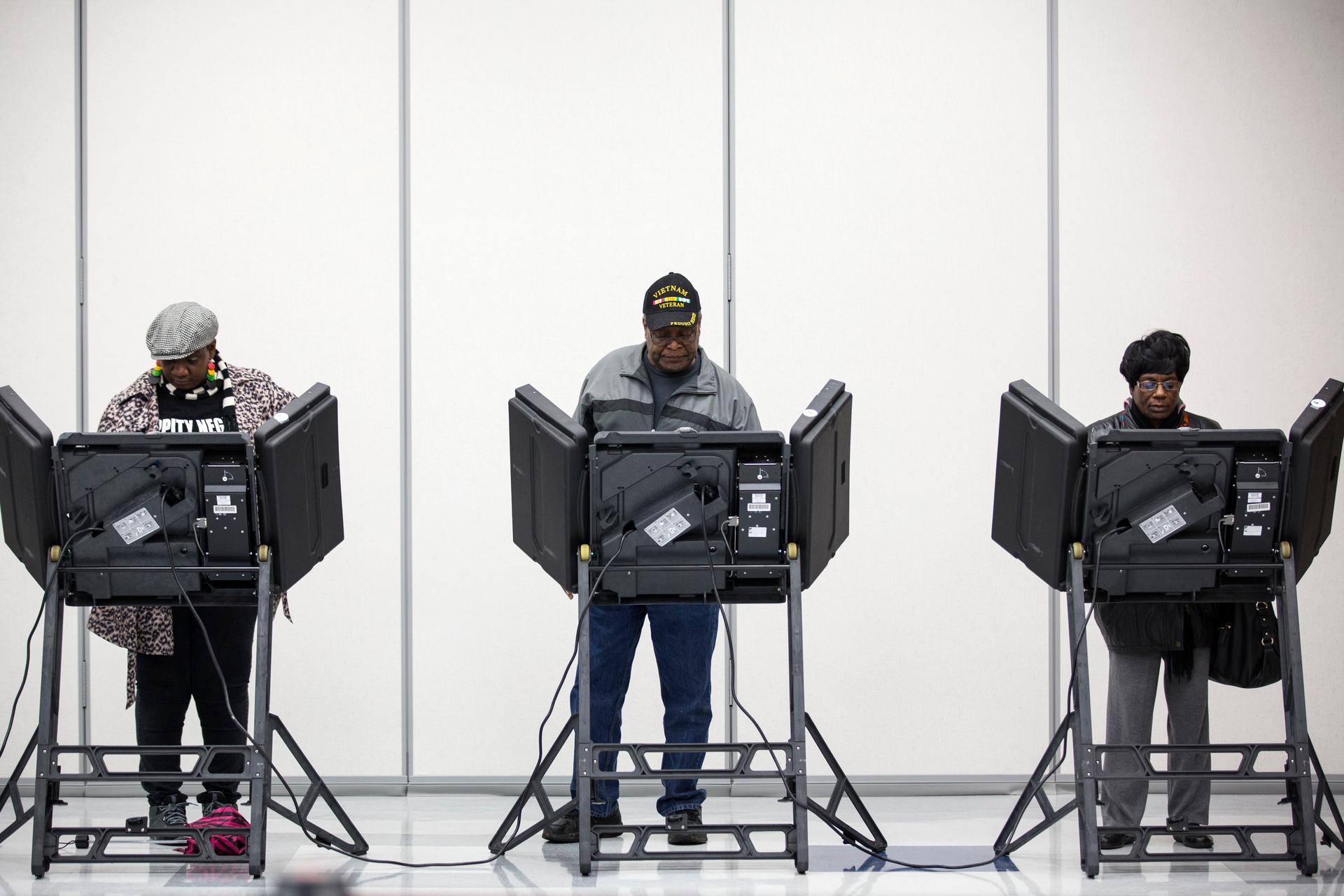

Voters cast their ballots in US midterm elections in Ferguson, Missouri, on November 4, 2014.

When Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965, non-white voters across the country faced a wide range of obstacles in getting to the polls. But has the “extraordinary problem” of voter discrimination really disappeared?

“Nearly 50 years later, things have changed dramatically,” argued Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts in the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision, which struck down the heart of the Voting Rights Act. Yet new political science research suggests that our voting system has simply traded one form of racial discrimination for another.

Ariel White and Noah Nathan, two co-authors of the first political science experiment to test implicit bias in the voting system in the modern era, concluded local election officials exhibit racial bias in how they implement election regulations and distribute key information to voters.

The study was prompted by a spate of new voter ID laws passed before the 2012 presidential election. “We have a lot of relatively confusing laws being passed, often relatively near to the election or being implemented at the last minute,” White says. “That’s where we worry that people who contact their local election officials may have a hard time getting information about these laws, and may then go on to not fully know how to go vote.”

The study doesn’t establish that voters are actively being suppressed, but it does show that election officials across the country discriminate against voters based on ethnicity.

“Different types of voters have different types of hurdles to overcome to get accurate information about what’s actually going to be required,” Nathan says. "Just because a law might in theory apply equally to everyone, in practice, when people interact with the bureaucrats implementing election laws, they might have very different experiences, and that might trickle down into whether or not they have the right information they need when they go to the polls.”

Electoral discrimination brings to mind Ava DuVernay’s recent film "Selma," which opens with a sneering white registrar denying civil rights activist Annie Lee Cooper — played by Oprah Winfrey — her voter registration on the basis of a twisted civics quiz. Such tests were later outlawed by Voting Rights Act.

That law effectively prevented this kind of bald-faced discrimination in some areas, giving particular scrutiny to the South. But White and Nathan's study uncovers implicit bias throughout the entire electoral system.

"What we’re actually finding is a much more subtle and implicit bias that is similar to bias that’s been found in all sorts of other experiments similar to ours in other fields — with loan officers, HR workers, doctors, real estate agents," Nathan says. "When people make discretionary decisions about others, they can be implicitly biased against minorities in how helpful they’re going to be — even if they don’t actually intend ill to those people.”

White, Nathan, and their co-author Julie Faller, all PhD candidates in government at Harvard, sent e-mails to over 7,000 local election officials in 48 states asking for basic information about voter registration and whether identification was needed on Election Day. They sent identical e-mails from names that sounded ostensibly white, and names that sounded ostensibly Latino.

While some officials did send correct information to both white and Latino voters, a disturbing pattern began to emerge.

“When we sent those e-mails — the same text of the same e-mail — from a Latino-sounding name, we got fewer responses overall," White says. "We more often heard radio silence. And we got slightly less thorough responses."

With the patchwork of new voter ID laws in 31 states, this kind of unconscious bias shifts discrimination from the poll site on Election Day to the weeks and months leading up to an election, when voters get the majority of their information on voting requirements.

“With an experiment like this, you can’t explain this bias away based on anything else," Nathan says. "These are exactly the same e-mails sent to thousands of people. Everything about them is the same. The ethnicity of the person sending them is the really only thing that could plausibly be causing these differences.”

Surprisingly, the mostly Southern and urban areas covered by the Voting Rights Act actually treated voters more fairly than other areas of the country.

“In these areas the officials didn’t discriminate in their responsiveness or in the accuracy of their responses to our questions,” Nathan says. “It’s suggestive evidence that when you have people looking over your shoulder and making sure that you aren’t biased, you aren’t biased.”

But White cautions that her study doesn't settle these issues. She wants more research into how implicit bias impacts voter behavior and election outcomes: “We do need a critical mass of social science research that can address this question,” White says.

This story is based on an interview from PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation.