Don Johnson, a former park ranger, on a fossil walk near his home on the Bonavista Peninsula in Newfoundland. As a kid, he used to climb on these rocks, but he says people here never know the fossils in these rocks were so significant.

One summer day in 2008, Jack Matthews and Alex Liu took their supervisor from the University of Oxford on a tour of their fossil finds on Newfoundland’s Bonavista Peninsula, on the eastern edge of Canada.

Their demonstration didn’t quite go according to plan.

"He stepped down onto the surface, sat down, turned to his side and said, ‘Well, what's this?’" Matthews remembers. The supervisor, the late Martin Brasier, noticed something in the rock beds that Matthews and Liu had completely missed. “He picked up what has turned out to be a very important fossil.”

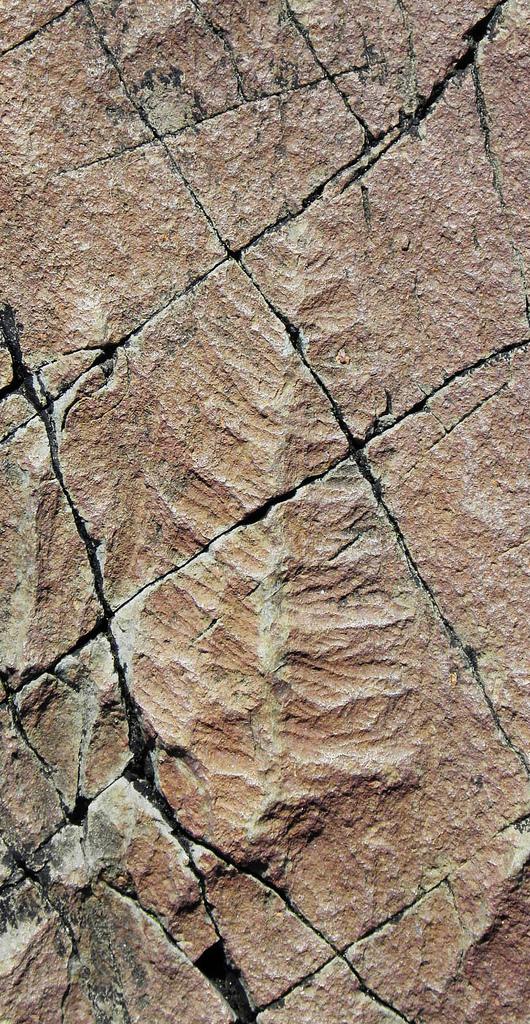

"Important” doesn't quite cut it. “We believe, if our interpretation is correct, that it is the oldest evidence of muscular tissue in the geological record,” Matthews says. It's now calledHaootia quadriformis: “Haoot” is a word used by the Beothuk, the aboriginal people of Newfoundland, for demon.

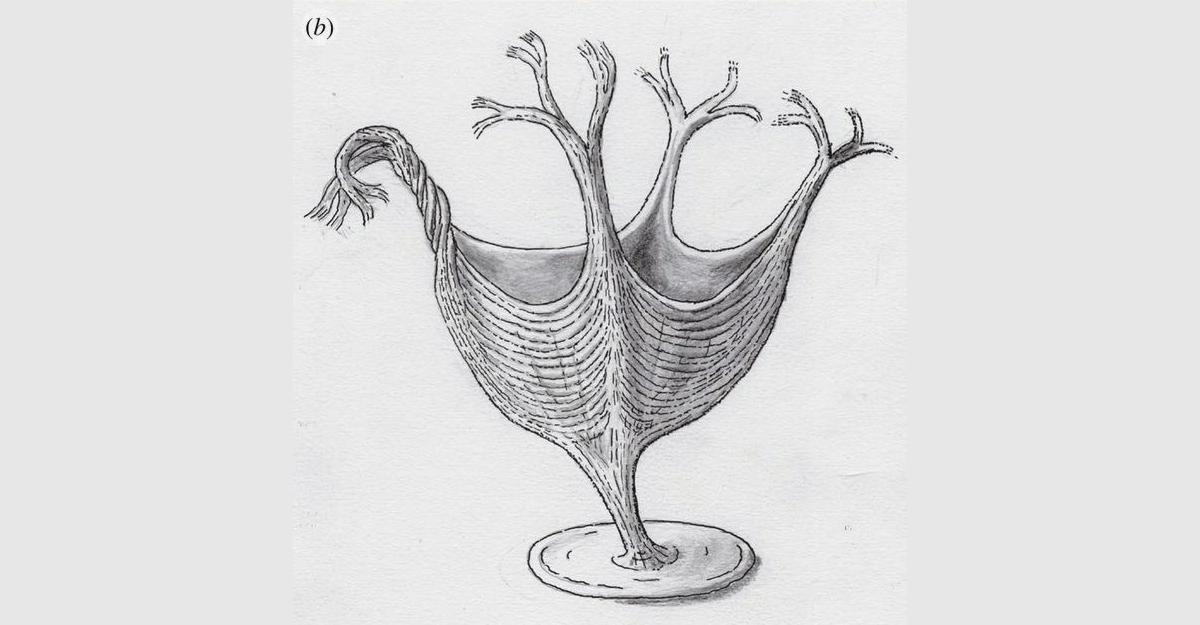

Picture a jellyfish the size and shape of a small wineglass. “It has a stem, which is similar to the stem of a glass, and then a bowl at the top. And that bowl is a sheet of muscle,”Matthews explains.

This is a big deal because Haootia was flexing its muscle in the Ediacaran period, about 560 million years ago. Before this find, scientists couldn't prove any animal was moving back then.

“This age has been referred to as the Ediacaran garden of Eden, because there was no predation going on yet there,” says Don Johnson, a former park ranger on the Bonavista Peninsula. He now gives geology walking tours for the Coaker Foundation, a historical society in the small community of Port Union.

“The Aspidella is lying down with the Charniodiscus, and everything is in peace," Johnson says, recounting the last days of the lazy animal peace. "Now you've got the devil there and he's moving around, and he's going to start eating things. Nothing is going to be the same.”

Johnson is enthralled with the Ediacaran geology and the knowledge that, from pools of bacteria at the dark depths of the ocean, bigger, complex life forms took shape. Now evidence of that can be seen in the rocks just a short walk from his home.

Newfoundlanders knew there were ancient Ediacaran fossils about 100 miles away, at a famous ecological reserve called Mistaken Point. But until these new discoveries, Johnson and others here had no idea that Bonavista's rocks were just as important.

“Since I was a kid climbing out over the rocks there, I never knew [fossils] were there, even though we walked over thousands of them,” Johnson says.

Haootia was discovered in 2008, but Liu, Matthews and their supervisor, Martin Brasier — who graciously shared this major find — didn't publish their study until the summer of 2014.

Johnson hopes the fossil discoveries will attract a different group of people: tourists. That seems likely if, as many here hope, the area is designated a UNESCO Geopark, one of a network of important geological sites. There are 100 Geoparks around the world, but only two in North America.

But a Geopark, unlike a national park, doesn’t get any extra funding. So the question for people here on the Bonavista Peninsula is how to balance the arrival of tourists with protecting what’s etched in the rocks.

Many people I spoke with in the area said that getting locals involved is the key to protection. But others worry that a thousand eyes in a community are no substitute for dedicated wardens like the ones in place at Mistaken Point. The fossils at Bonavista are protected by a law and hefty fines, but enforcement is left to local police.

“I think there may be a need for some sort of professional oversight,” Johnson says, “just to keep an eye out.”

As for Haootia, Bonavista’s now-famous fossil, the Newfoundland government decided there was only one way to protect it: In the fall of 2014, they cut it out of the rock and put it on display at The Rooms, a museum in Newfoundland.