In a region of turmoil, the new Saudi king promises continuity

Mourners gather around the grave of Saudi King Abdullah following his burial in Riyadh on Friday.

The 90-year-old monarch of Saudi Arabia was laid to rest in the capital of Riyadh today. In accordance with religious tradition in the ultraconservative Sunni kingdom, Abdullah’s body was wrapped in a tan cloth and buried in a simple grave.

Islamic beliefs says that all of God’s subjects are equal in death, even a man whose official title includes the designation of Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques.

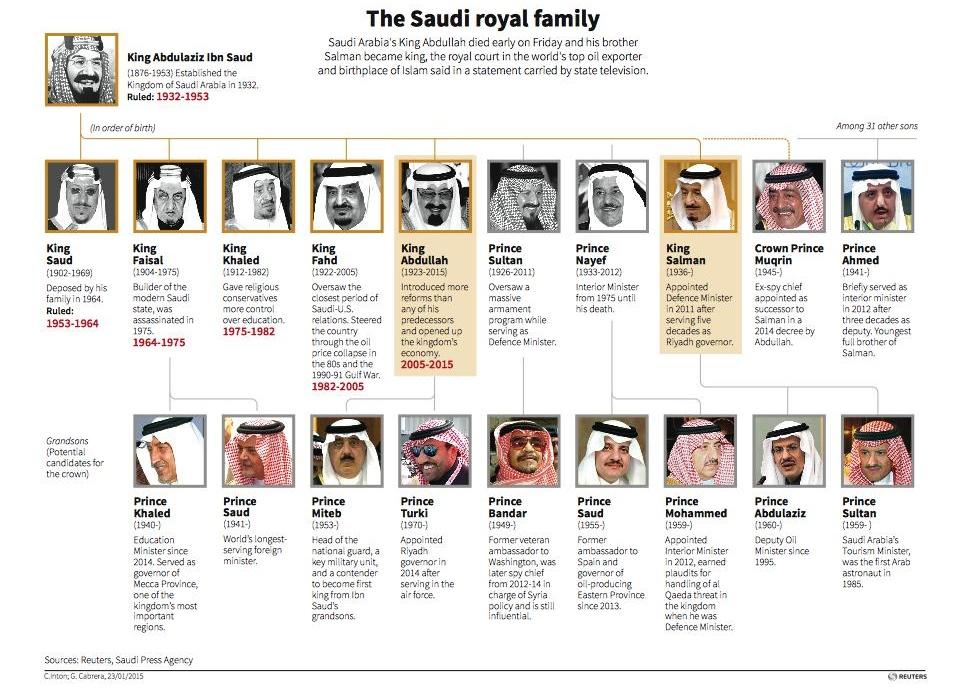

The new Saudi king is Abdullah’s nearly 80-year-old half-brother, Salman, who moved quickly to pre-empt any possible intrigue about the process of royal succession.

“With God’s assistance and strength, we will continue adhering to the correct policies since the establishment of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,” Salman said during a televised speech.

Salman’s 69-year-old half-brother, Murqin, was named Crown Prince and immediate successor to the throne. And for the first time, a member of the next generation in the House of Saud is officially in line to be king. As deputy crown prince, Prince Mohammed bin-Nayef, 55, is the second-in-line.

King Salman gave the job of defense minister to his son, Mohammed, and other top ministers remained in place.

During previous times of transition, intra-family politics in the Saudi royal family have erupted in division and put the dynasty’s grip on power in danger. King Salman sought to ease such fears by promising continuity.

Salman’s biography itself suggests continuity. As a member of the inner circle of the Saudi ruling class and a former governor of the province of Riyadh, Salman is a known quantity among all those at the highest levels of power, says longtime New York Times correspondent Robert Worth.

“[King Salman] doesn’t have quite the authority of his predecessor,” Worth says. “King Abdullah was popular, unlike King Fahd the previous king, with the [Saudi] people because he was known to be a pious man.”

Salman might not have the same reputation for personal virtue, Worth adds, but neither is he known as a corrupt leader. “I don’t think he’s going to challenge a lot of [existing] policies,” Worth says.

The most immediate challenge for Salman could prove to be the chaos next door in Yemen, where Houthi rebels have brought the Saudi-backed government to its knees. In Sunni Saudi Arabia’s eyes, the Houthis are Shia Muslims and natural allies of the Saudis’ most powerful regional rival, Iran.

The new king has other things to worry about. Among them are the ISIS extremists who control parts of Syria and Iraq and view the Saudi government as an enemy. Saudi Arabia is part of the US-backed anti-ISIS military coalition. Then there is al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, based across the border in Yemen, which Saudi security and intelligence forces have been fighting for years.

Salman will want to reassure his allies in Washington as well. Successive American administrations have seen Saudi Arabia as a useful partner in an unstable part of the world. Caryle Murphy, who wrote a book called "A Kingdom’s Future: Saudi Arabia Through the Eyes of Its Twentysomethings,” doesn't see that dynamic changing now that there is a new leader at the helm in Saudi Arabia.

Murphy, who has lived and worked in Saudi Arabia for years, says Saudi Arabia will continue to be a US ally even if it doesn't have a great track record on human rights.

“Our [the United States] main goal right now in the region is stability. Saudi Arabia is probably the most stable country at the moment, so the Americans are going a little soft on Saudi Arabia human rights abuses and repressions because they don’t want to rock the boat,” she says.

In addition to the help the Saudis are contributing in the fight against ISIS, Murphy says Riyadh and Washington are working together in Syria. The Saudi government has promised to help train Syrian rebels. And Murphy says it has been clamping down on donations from Saudi citizens to extremist groups like ISIS.

Murphy doesn’t see why the US would want to reassess its relationship with Saudi Arabia, especially at a time when so much of the region is going through turmoil.

“If you are a policy maker sitting in Washington and you see Saudi Arabia keeping things relatively stable in a very very important Muslim country … why would you want to reassess that relationship right now?” she asks.

Abdullah is being described in news reports as a “moderate reformer” — a label some are calling laughable. Fawziah al-Bakr, a women's rights activist and a professor at King Saud University in Riyadh, disagrees.

“King Abdullah's passing is a great loss,” she says, “because King Abdullah did so much for women.”

Al-Bakr says Abdullah started a scholarship program for women and brought women into government. “We’re just feeling so sad,” she adds.

There was speculation that King Abdullah would overturn the ban on women driving, which never came to pass. “We expected a lot from him,” al-Bakr says. “We still have to work so hard to overcome so many negative aspects of our laws against women.”

When it comes to the issues of human rights and freedom of speech, Murphy thinks any change should (and will) come from within Saudi Arabia itself. The US doesn’t really have much leverage over such internal matters.

“When George Bush came out promoting democracy in Saudi Arabia after the 9/11 attacks, Saudi Arabians just got angry and turned a blind eye,” she says.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?