US censors make 2,500 cuts to first-ever published diary by Guantanamo detainee

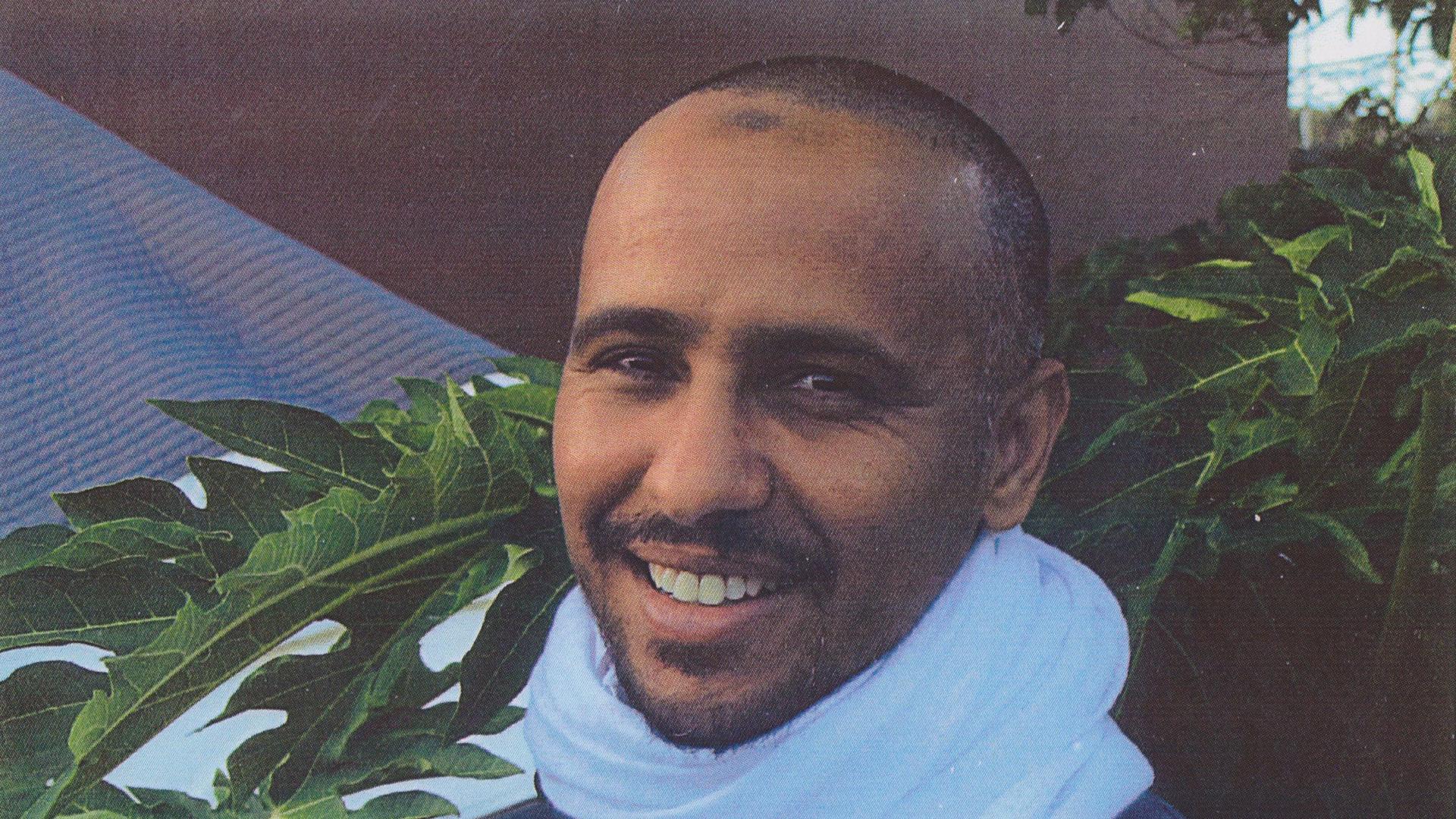

Mohamedou Ould Slahi has been imprisoned at Guantánamo since 2002 without charges.

It took six years to win the declassification of the first-ever memoir published by a detainee at the Guantanamo Bay detention center — part of it, at least.

That memoir, Mohamedou Ould Slahi's "Guantánamo Diary," includes no less than 2,500 redactions, the black bars government censors use to make certain passages unreadable.

Larry Siems, the book's editor, says some of the redactions border on the absurd. At one point, Slahi describes being moved out of his cell for the first time.

"He describes a Puerto Rican division of guards, one of whom reaches out and touches him on the shoulder and says, 'It's okay, you're gonna go home soon,'" Siems says. "He breaks into tears. But when he writes it, he says, 'I couldn't help breaking into' and then [censors] redact the word."

Slahi also wrote a poem that takes up two pages of the book. The poetry is entirely redacted.

Much of Slahi's story is already well-known. He grew up in small town in Mauritania and won a scholarship to study in Germany. In 1990, he traveled to Afghanistan and swore allegiance to al-Qaeda, a decision he would eventually reverse.

But in 2001, he was arrested in Mauritania and began what he calls his "world tour" of interrogation centers, going from Jordan to Afghanistan to Guantanamo, where he's been incarcerated for more than 12 years.

Slahi has never been charged with a crime. The judge in his case ruled in 2010 that all the evidence against him was obtained via torture or coercion, or was otherwise not credible. The US government appealed that decision, and the case has been in limbo ever since.

The 44-year-old wrote more than 400 pages of the book from prison, some scrawled, others neatly written, and all in English — his fourth language, which he says he learned in detention.

In a passage early in the book, Slahi describes what it's like to disembark from a 30-hour flight, crammed in with other detainees on the trip from Afghanistan to Cuba. Slahi is riveted by the English phrases the guards use as they bark orders.

"He's in the middle of this most extreme moment," Siems says. "You can imagine the fear, the terror, the exhaustion — and yet he's drawn out of himself by just a curiosity about the fact that the Americans have two imperative ways of saying 'Don't talk.'"

After he arrives at Guantanamo, Slahi struggles to understand his guards and interrogators.

"He talks about the kinder jailers, who discuss with him theology and politics and give him books, and provide a way for him to engage in a really de-humanized environment," says Hina Shamsi, who directs the ACLU's National Security Project and is one of Slahi's lawyers. "These are people who sometimes come around and say to him, 'You know, you shouldn't be here.'"

And there's lots of humor, including Slahi's handwritten note to his attorney who asks him to write down everything he's told his interrogators for the last seven years. "Are you out of your mind?" Slahi writes. "That's like asking Charlie Sheen how many women he dated."

Lt. Col. Myles Caggins, a Pentagon spokesman, says American officials censored passages of "Guantánamo Diary" out of concern for national security.

"Those redaction decisions were the product of lengthy interagency discussions between the Defense Department [and] intel branches to make sure the information released would not harm US personal or damage national security," Caggins says. "Information was redacted if its release would compromise our anti-terrorism efforts, our operations abroad or place US troops, government civilian employees or their families at risk."

Caggins says Slahi might ultimately be freed from Guantanamo. "It's possible that Slahi could go through a periodic review board and be put in a pool of detainees that we call 'eligible for transfer,'" he says.

He also admitted he might pick up a copy of "Guantánamo Diary" sometime soon.

"I haven't yet read the book, but I look forward to reading it," Caggins says. "It's of interest to many of us in the Defense Department who follow Guantanamo issues, and it's part of our country's history."

Read an excerpt from "Guantánamo Diary" by Mohamedou Ould Slahi, courtesy of Little, Brown and Company.