In a rare interview, Snowden urges the US to play defense, not offense, in cyberwarfare

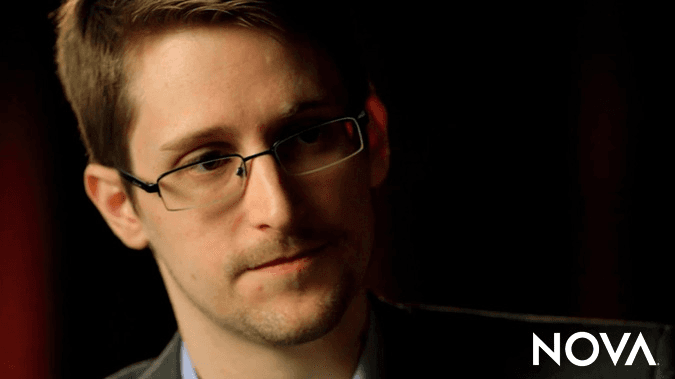

Former NSA contractor Edward Snowden urges the US to go on defense in cyberwarfare. He spoke in Moscow in an interview for an upcoming NOVA documentary.

Former NSA contractor Edward Snowden is pushing a strong defense, rather than offense, for American cyberwarfare.

In a rare interview for an upcoming NOVA documentary, Snowden said the US has the most to lose by taking the offense in a cyberwar. Speaking from Moscow, the man who publicized NSA secrets compared the efforts to exploit national secrets to bank robbers seeking entry to vaults. "In relative terms, we gain much less from breaking into the vaults of others than we do from having others break into our vaults," he said.

He used an exotic reference to explain the damage from the unintended consequences of advanced cyberwarfare, which he dated to the Stuxnet computer virus unleased upon Iran in 2009 and 2010. The virus, introduced through an infected thumb drive, targeted the Natanz uranium enrichment plant, seeking to render centrifuges inoperable and thwart Iran's possible development of nuclear weaponry.

The problem is two-fold, said Snowden in the June 30 interview: Others went on offense in cyberwarfare and some viruses are extremely difficult to combat. "When we put the little evil virus in the big pool for private lives, our private systems on the Intenet, it tends to escape and go all 'Jurassic Park' on us,'' Snowden said.

Excerpts of the text of the interview are below:

—–

On Iran: "I think the public still isn’t aware of the frequency with which these cyber-attacks, as they’re being called in the press, are being used by governments around the world, not just the US. But it is important to highlight that we really started this trend in many ways when we launched the Stuxnet campaign against the Iranian nuclear program. It actually kicked off a response, sort of retaliatory action from Iran, where they realized they had been caught unprepared. They were far behind the technological curve as compared to the United States and most other countries. And this is happening across the world nowadays, where they realize that they’re caught out. They’re vulnerable. They have no capacity to retaliate to any sort of cyber campaign brought against them."

"The Iranians targeted open commercial companies of US allies. Saudi Aramco, the oil company there — they sent what’s called a wiper virus, which is actually sort of a Fisher Price, baby’s first hack kind of a cyber-campaign. It’s not sophisticated. It’s not elegant. You just send a worm, basically a self-replicating piece of malicious software, into the targeted network. It then replicates itself automatically across the internal network, and then it simply erases all of the machines. So people go into work the next day and nothing turns on. And it puts them out of business for a period of time."

—–

The problem with playing offense: "When it comes to cyber warfare, we have more to lose than any other nation on earth. The technical sector is the backbone of the American economy, and if we start engaging in these kind of behaviors, in these kind of attacks, we’re setting a standard, we’re creating a new international norm of behavior that says this is what nations do. This is what developed nations do. This is what democratic nations do. So other countries that don’t have as much respect for the rules as we do will go even further."

"And the reality is when it comes to cyber conflicts between, say, America and China or even a Middle Eastern nation, an African nation, a Latin American nation, a European nation, we have more to lose. If we attack a Chinese university and steal the secrets of their research program, how likely is it that that is going to be more valuable to the United States than when the Chinese retaliate and steal secrets from a US university, from a US defense contractor, from a US military agency?"

—–

Expanding purview: "The way the United States intelligence community operates is it doesn’t limit itself to the protection of the homeland. It doesn’t limit itself to countering terrorist threats, countering nuclear proliferation. It’s also used for economic espionage, for political spying to gain some knowledge of what other countries are doing. And over the last decade, that sort of went too far. No one would argue that it’s in the United States’ interest to have independent knowledge of the plans and intentions of foreign countries. But we need to think about where to draw the line on these kind of operations so we’re not always attacking our allies, the people we trust, the people we need to rely on, and to have them in turn rely on us."

"There’s no benefit to the United States hacking Angela Merkel’s cell phone. President Obama said if he needed to know what she was thinking, he would just pick up the phone and call her. But he was apparently allegedly unaware that the NSA was doing precisely that. These are similar things we see happening in Brazil and France and Germany and all these other countries, these allied nations around the world."

"And we also need to remember that when we talk about computer network exploitation, computer network attack, we’re not just talking about your home PC. We’re not just talking about a control system in a factory somewhere. We’re talking about your cell phone, and we’re also talking about internet routers themselves. The NSA and its sister agencies are attacking the critical infrastructure of the internet to try to take ownership of it. They hack the routers that connect nations to the internet itself."

—–

The consequences: "And it’s important to remember when you start doing things like attacking hospitals, when you start doing things like attacking universities, when you start attacking things like internet exchange points, when something goes wrong, people can die. If a hospital’s infrastructure is affected, lifesaving equipment turns off."

"When an internet exchange point goes offline and voice over IP calls with the common method of communication — cell phone networks rout through internet communications points nowadays — people can’t call 911. Buildings burn down. All because we wanted to spy on somebody."

"So we need to be very careful about where we draw the line and what is absolutely necessary and proportionate to the threat that we face at any given time. I don’t think there’s anything, any threat out there today that anyone can point to, that justifies placing an entire population under mass surveillance. I don’t think there’s any threat that we face from some terrorist in Yemen that says we need to hack a hospital in Hong Kong or Berlin or Rio de Janeiro.''