Syria is at the center of a booming trade in a little pill that’s cheap, easy to produce and completely illegal

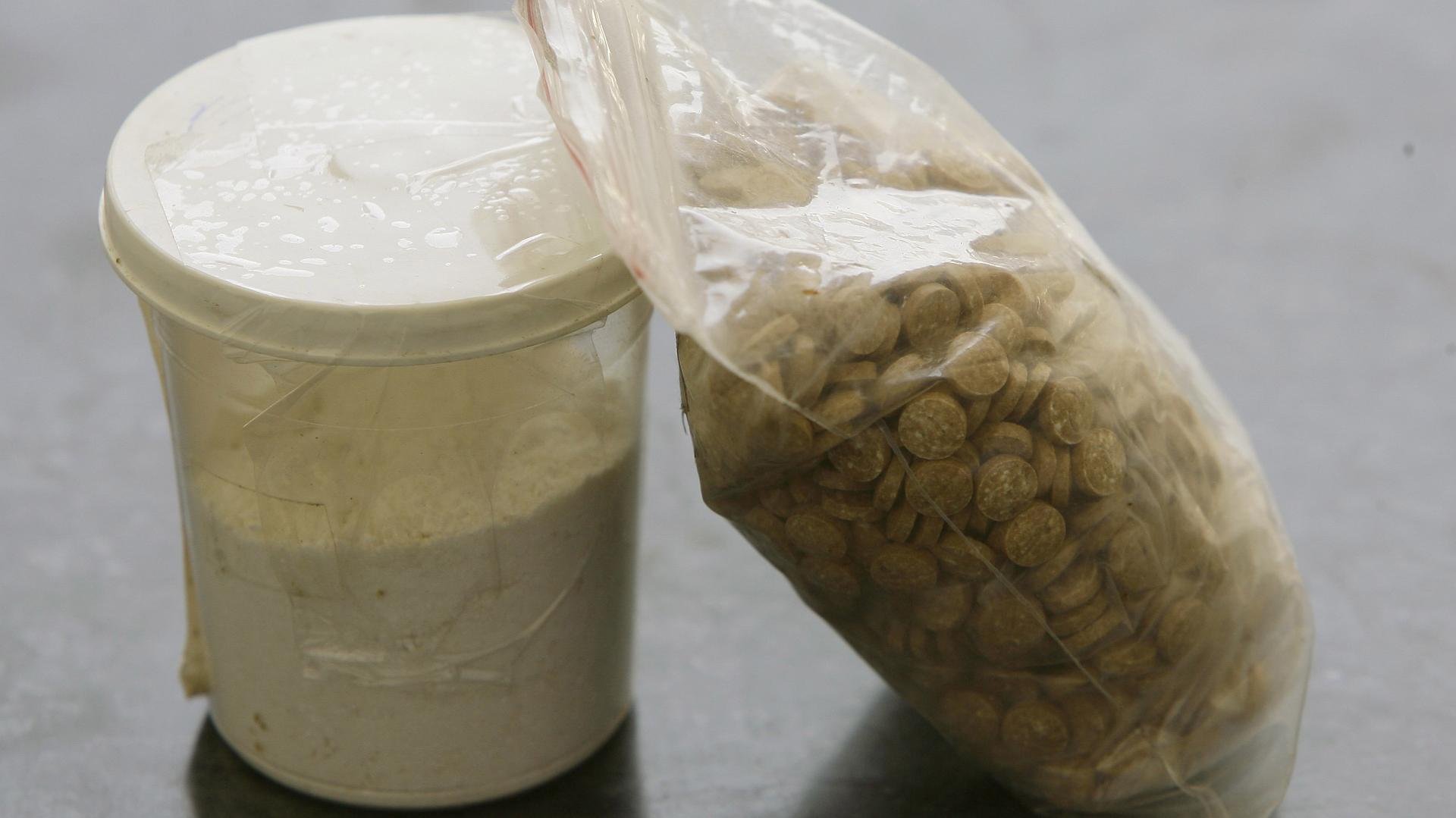

Captagon pills are displayed along with a cup of cocaine at an office of the Lebanese Internal Security Forces (ISF), Anti-Narcotics Division in Beirut on June 11, 2010.

Syrians on speed. Jihadis addicted to uppers. Drug cartel lackeys setting up illegal pill factories in crappy hole-in-the-wall spaces in Beirut while the top boss lives in splendor outside some European capital.

This isn't a movie plot; this is a real story about a drug that's little known in the West, but is running wild in the Middle East: captagon.

Chavela Madlena produced a documentary about captagon that aired on BBC Arabic. She wrote about it for ForeignPolicy.com.

"Captagon is an illegal version of a drug invented by the German pharmaceutical giant AG Degussa in the 1960s. It was originally supposed to treat everything from attention deficit disorder to being a popular dieting aid." But all that changed in the mid-1980s. "That's when the World Health Organization and the FDA concluded it was more addictive and harmful than good. It was just eventually one of those amphetamines that kind of just fell away."

Now an illegal version of it is in high demand across Syria, fueled by the country's civil war. Madlena and her documentary team visited an illegal pill factory in Beirut. The people running the Beirut drug factory would only let their cameraman in.

"What he described was one of those kind of garage/storage units." The workers were all men, under 30, with tattoos. There were boxes of precursor chemicals, like quinine, caffeine and liquid and powder forms of different chemicals. "They call it captagon, but it's not actually the old form of captagon that was made by pharmacuetical companies. It's a combination of things," she says. "The workers said everybody has their own special recipe, their own special flavors they put in. Just like sheesha or water pipes."

The effect of captagon is like taking speed. "I've seen everything from it being reported as keeping people calm to making them crazed. It's an amphetamine," says Madlena. "It keeps you awake and then when you stay awake for a long period of time, you are massively susceptible to sleep deprivation psychosis and all the concommitant medical issues that come along with not sleeping and being on a powerful stimulant and psychotropic drug."

Before the Syrian war, the demand for captagon was mostly in Saudi Arabia. An addiction counselor in Kuwait told her why: Because alcohol is such a taboo and heroin is such a taboo — and they're both not really condusive to being functional.

Amphetamines are much cheaper and easier to integrate into your daily life. And there's less stigma around something that was once a prescription pill. Saudi housewives use it to lose weight. Saudi students use it to study. Truck drivers use it to stay awake. A huge market is people in the military. Madlena interviewed a former addict in Kuwait who had been a soldier.

"He took captagon, which ended up for him being a gateway drug into other things. He said it was rife in his community, which is a lower socio-economic [class], less educated. Lots of guys working in the army or in law enforcement."

Since 2011, demand for captagon has grown in Syria and there's evidence that the Paris attackers were high on Captagon. If it's proved to be true, it won't surprise Madlena. "From speaking with former Syrian fighters, this pill is rife on the battlefield there. It's also in areas where we know that former criminal syndicates had factories and supply lines, smuggling pills out before the war and and now those areas are controlled by ISIS. It's cheap and readily available. It doesn't surprise me."

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?