This woman demonstrated that even in Russia all politics is local

Natalia Pinus decided to run for the Novosibirsk City Council in Siberia. And she decided to run as an independent.

When you hear about politics in Russia, it’s almost always about Vladimir Putin — whether it’s bulldozing piles of cheese or approving airstrikes on Syria — commanding from on high. But at the regional level, things are very different. Here’s a story about Russian politics writ small.

My friend, Sarah Lindemann, is an American who moved to Novosibirsk in Siberia in 1989. Late this summer, she started blogging about a local city council election in her district of Akademgorodok, which means “Academy Town.” It’s home to the state university and many famous scientific institutes — kind of a Madison, Wisconsin or a Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Anyway, Sarah decided to follow one particular candidate, Natalia Pinus, mother of three, successful businesswoman, head of the local community foundation. Out of six candidates, she was the only woman.

According to Sarah, that opened her up to criticism like “How can someone with three children have so much time?”

Out of 39 people on the Novosibirsk city council, only four were women. Even more unusual — Natalia Pinus was running as an independent.

“All the parties except for, you know, basically the closest to a Fascist party we have, approached her about representing them,” Sarah says.

But Pinus ended up rejecting Putin’s United Russia, the opposition parties — everyone. This meant no access to party money, while some of her opponents had plenty — like Nikita Galitarov, the son of a construction mogul.

“He plowed probably 20 million rubles [about $320,000] into his campaign. So you couldn’t NOT know his name,” Sarah says.

So instead of billboards, Pinus asked residents to hang her banners from their balconies. Her office was a local coffeeshop. Oh, and the other thing about Galitarov?

“He didn’t live here, didn’t work here, had absolutely no connection to the community,” Sarah says.

At the sole debate, Galitarov showed up only to explain that he had a scheduling conflict and wouldn’t be able to participate. The debate was streamed online and when the online votes were tallied, Natalia Pinus was declared the winner. She held open meetings throughout the district, and was the only candidate to develop a platform based on the feedback of actual residents.

Her grassroots campaign was running smoothly. But so was Galitarov’s, in a way.

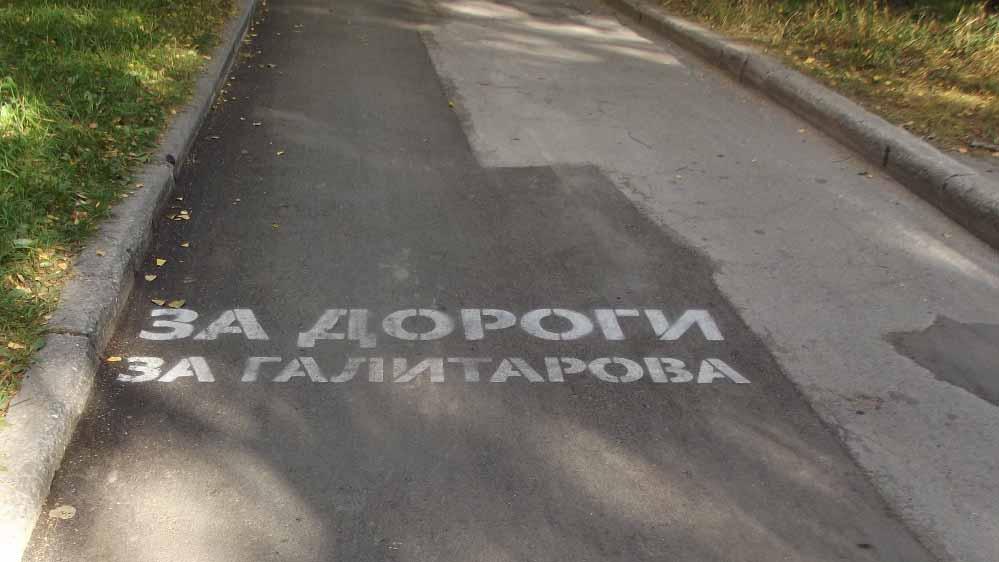

“All of a sudden, these teams of trucks and workers showed up all over town and started asphalting all the streets and sidewalks and then stamping them with ‘For Roads, For Galitarov,’ ” Sarah says.

This was actually a popular gambit during the Soviet days. “Right before an election, some little piece of street would get asphalt so it brought hope. And people [would] think, Oh good, the guy really gets things done.”

Thing is, Pinus was already known for getting things done. As head of the local community foundation, she got a duck pond constructed. “That may seem kind of preposterous but she did something that really benefitted the community,” says Fiona Hill, a Russia expert at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC, who followed the election on Sarah’s blog.

“And it was the fact that [Natalia Pinus] did something that had direct benefit to her community that made her very effective and got her name recognition. Not because she ran some flash campaign.”

The week before the September 13 election, when it was clear the two frontrunners were Pinus and Galitarov, things got ugly. A mock newspaper was distributed accusing Pinus of being part of the go-go 90s oligarch crowd that destroyed Russia’s economy. An anti-Natalia barker appeared on the main street in Akademgorodok.

Even on election eve, it was still unclear how the vote would go. Remember, this is a city that stunned the nation by electing a Communist mayor over the United Russia candidate last April. So would Galitarov’s modern version of Soviet-era politicking win the day?

“I don’t know, maybe it was 2 in the morning and [Natalia’s] phone rang. And she was talking and it was very serious,” Sarah says. “Then she got off and she didn’t say anything and so we were like, who was that?”

It was Galitarov, calling to congratulate Pinus for running an honest campaign — and for winning.

It was, by all accounts, a fair election, won by an outsider candidate without party backing on a shoestring budget. So what does it say about democracy in Russia?

“It depends on how we're defining democracy, but if we’re talking about grassroots participation, in spite of everything, in spite of what things might look like at the top, or the fixations of people in Moscow or certain small circles in Moscow, people can still get things done.”

If you can count on anything, count on Russian politics to confound you.