German atheists seek recognition for ‘Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster’

Rüdiger Weida, aka “Bruder Spaghettus”, founded a church dedicated to the worship of “the Flying Spaghetti Monster” in Templin, Germany.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel was in Rome over the weekend and said she had a “very cordial” meeting with Pope Francis. That’s not so surprising for the daughter of a Lutheran pastor, who recently expressed how her Christian faith had an “important” place in her life.

But these are the kinds of news tidbits that rub Rüdiger Weida the wrong way. He is convinced that religion holds a privileged place in German society and that non-believers lack the same civil rights.

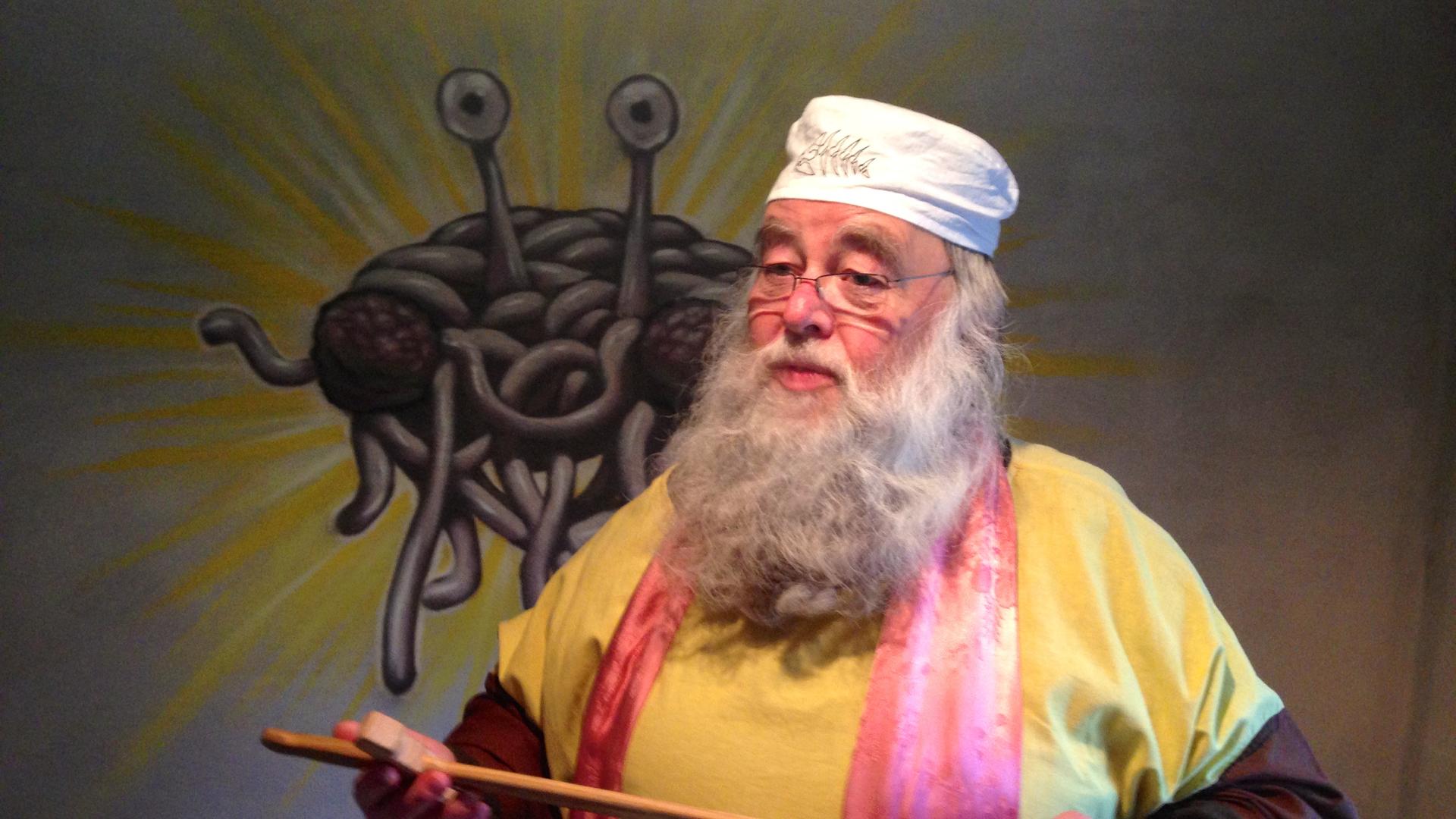

Weida is a 63-year-old retiree who lives in the town of Templin. It’s about an hour’s drive outside of Berlin and happens to be Angela Merkel’s hometown. Templin is also where Weida founded the “Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster,” in September last year. As one of the leading “Pastafarians” at the church, or non-church more accurately, Weida goes by the alias of “Bruder Spaghettus.”

Weekly “Noodle Worship” begins at 10 a.m. Fridays in a small building on Weida’s farmstead on the outskirts of town. It looks and feels somewhat like weekly worship services at mainstream Christian churches. There is an altar, time for prayers, scripture readings, hymns, and even a version of Holy Communion. But the similarities end pretty quickly.

In Weida’s church, wine and bread are replaced by beer and, you guessed it, cooked strands of spaghetti. “Amen” is replaced by “Ramen," and at the end of the service there are exhortations of “Beer-alleluia.”

Weida presided over the service as the “Noodler,” wearing a long yellow robe and a pink stole. The congregants, and there were only two of them on the chilly morning I paid a visit, dressed up like pirates. Behind the altar was a painting of the church’s giant pasta deity. And in the next room, there were chairs for less formal gatherings of the faithful and a big banner that said, “Down with disbelief.”*

After the service finished, I asked Weida if he actually believed in the divine nature of the “Flying Spaghetti Monster.” “It’s a hard question for a Pastafarian,” he said. “We are all separated into two persons inside.”

“Of course, I believe. But, of course, I also know it doesn’t exist,” Weida explained.

Weida said he doesn’t see himself strictly as an atheist, but rather a humanist. “We are also not a religious group,” Weida explained. “But we adhere to a Weltanschauung,” or a complete worldview. The more I asked for details about that worldview, the more ridiculous the answers got. For example, on the question of heaven, Weida said Pastafarians believe in a heaven-like existence in the afterlife that includes large amounts of beer and great numbers of strippers.

Pastafarianism actually started about a decade ago in the United States. A 24-year-old physics graduate named Bobby Henderson introduced the deity of the Flying Spaghetti Monster in an open letter of protest to education officials in Kansas. They had proposed teaching intelligent design in biology classes. Henderson’s letter went viral. And it spawned a largely Internet-based movement.

Weida told me he believes in freedom of religion, but that he doesn't have much respect for mainstream organized religion. He is pushing for official recognition of his church to make a political statement about what he sees as the privileged position that religious organizations have in German society.

“With employment laws, for example, churches can hire and fire people based on their beliefs,” he said. “Mainstream churches also get government funding to run their institutions (such as hospitals or elderly care centers)."

Essentially, Weida wants to push for legal recognition for his own church in order to make a statement about the rights of non-believers. And he is having some success.

The mayor of Templin, Detlaf Tabbert does not go to any church himself. But he decided to give the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster permission to put up official signs in town letting everyone know where and when to attend "Noodle Worship" services.

“We live in a tolerant place and we shouldn't discriminate against minorities,” Tabbert said. “People should also be able to deal with criticism and have a sense of humor.”

But Thomas Hoehle told me the Pastafarians are trying to have it both ways. He's a priest at the Heart of Jesus Catholic Church in Templin. “It's obviously not a real church,” Hoehle told me. “It's a parody of a church.”

Hoehle said that he cannot take Weida and the Pastafarians very seriously, because their goal appears to be to mock the Catholic liturgy and belief. “We need to be respectful of different faiths,” Hoehle said. “And this parody church is hurtful.”

Some high-level German officials might feel the very same way. They want town hall in Templin to take down those signs about “Noodle Worship.” Or, at the very least, not to pay for them with public funds.

*UPDATE: This translation of the banner in the church has been changed to "Down with disbelief" to more accurately reflect the intention of the church. Weida said the group, familiar to disparagement, seeks not to disparage individuals.

Readers, do you think the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster should be fully recognized? Would you want such a church in your community? Let us know in the comments section below.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?