The world’s fastest sport isn’t the one you’re thinking of

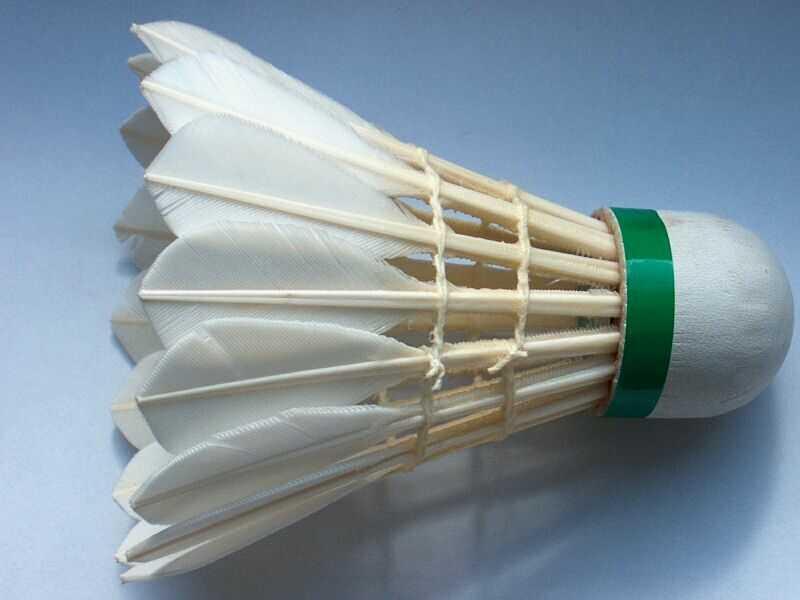

A badminton shuttlecock, or birdie, is designed to always fly nose first and slow down after its hit.

What’s the fastest sport in the world? Tennis? No. Soccer? Baseball? No and no. It's badminton — in which the birdie, or shuttle, as the pros call it, can travel more than 200 mph.

Badminton has diverse roots: It grew up in ancient Greece, China, Japan and India, and its current regulations were developed in England. The game was brought to the United States in the 19th century, and the first American badminton club opened in New York in 1878.

The rules have changed over time, but the one constant has been the shuttlecock.

The shuttle, made with a cork base and sixteen carefully selected goose feathers, is aerodynamic and very light — weighing only about five grams. No matter how the shuttle is hit, it will fly nose first. The feathers create drag, which leads to a more predictable flight path, giving the player more control over shots.

“It’s a unique shape for a projectile, compared to other sports,” says Dr. Qin “Arthur” Zhu, a kinesiologist at the University of Wyoming. “All other ball sports created the ball to make it fly faster. The shuttlecock is made to actually slow down after being hit.”

In addition to his work as a kinesiologist, Dr. Zhu is a national badminton umpire and a top player and coach who trained in China. To improve his coaching techniques, Zhu set out to understand how players could transfer the most speed from their bodies to the shuttlecock.

He examined all aspects of the players' swing by hooking them up to a series of sensors and recording their movements in precise detail. By studying the racquet angle of novice players, recreational players and expert players, Zhu found that 71.6 degrees is optimal for transferring the most speed to the shuttlecock.

But that angle is difficult to achieve with every shot unless you are a very experienced player. If less expert players want to make the shuttle fly faster, they can gently bend the feathers inward, reducing the air resistance.

Just don't try this during a professional match: it's cheating. So it might be best to keep working on improving that racquet angle — especially if Dr. Zhu is watching.

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?