We actually pay CEOs like menial laborers — and here’s why

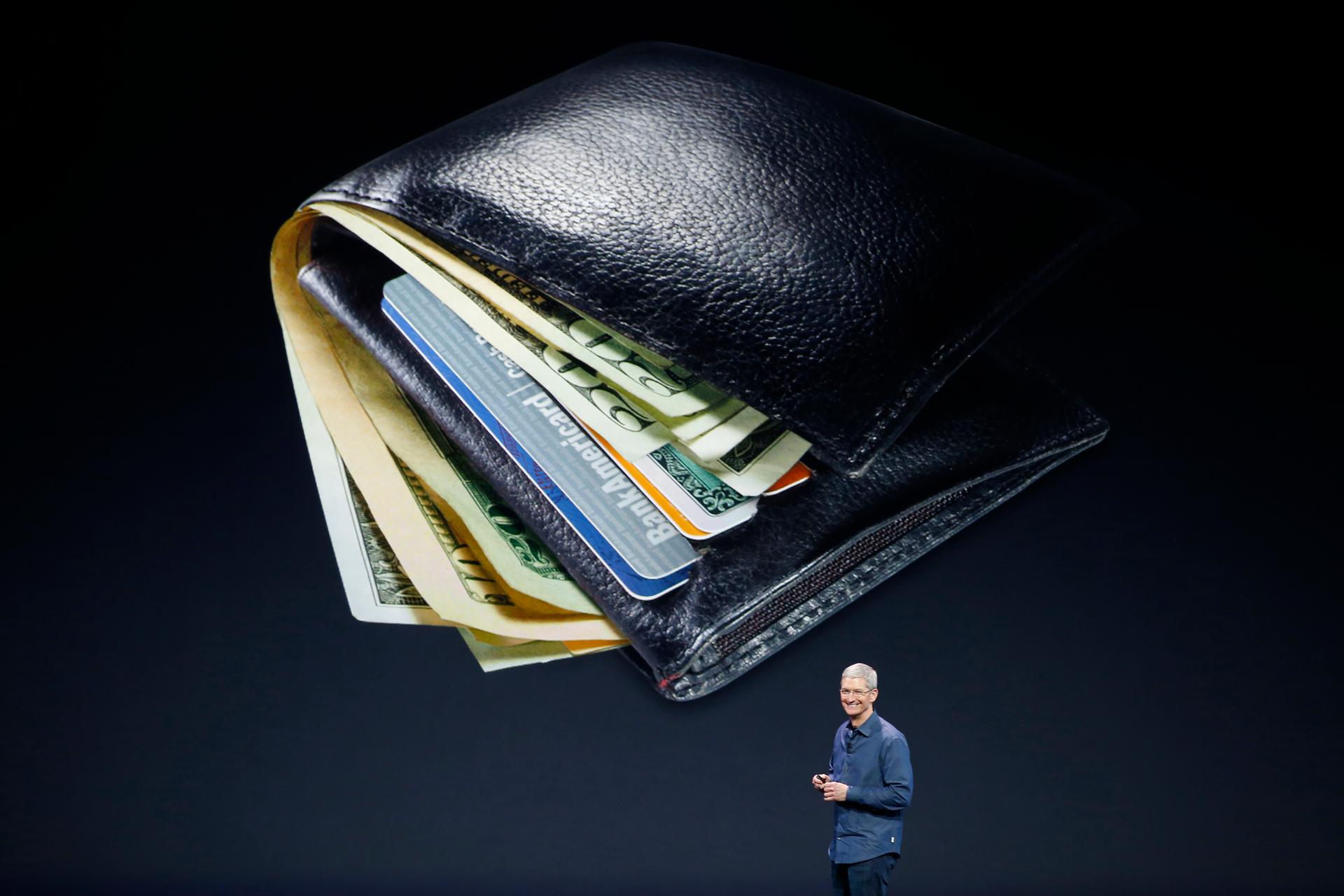

Apple CEO Tim Cook speaks about Apple Pay during an Apple event at the Flint Center in Cupertino, California, on September 9, 2014.

The super-rich Americans of the 20th century tended to have lots and lots of a thing — say, oil, if you were a Rockefeller, or steel if you were a Carnegie. But look around today: The country isn't exactly full of timber barons.

That's because the US economy underwent a major transformation starting in the 1960s, argues Roger Martin, a management expert and author of the article “The Rise and Likely Fall of the Talent Economy.”

Around that time, companies found they could gain a competitive advantage by hiring highly talented people to invent new products and market them to consumers. Companies like Proctor & Gamble and General Electric rose to the top, while resource giants like Bethlehem Steel and Sinclair Oil began to falter.

“Talent started to say, ‘Hey, it’s not the capital, it’s not the people with the money bags, and it’s not the people with the natural resources — it’s me,” Martin says.

The growth of that "knowledge economy" has largely been a good thing for innovation. Leaders of tech companies get paid a lot of money because they create products people find useful and are willing to pay for. And when their companies become successful, they hire more people and grow the economy.

“It’s a positive-sum game,” Martin says.

But that isn’t the case across the board. Hedge fund managers, for example, make their money trading public securities. “It’s a zero-sum game, which doesn’t really create much societal value,” Martin says. Still, "it’s definitely the industry that is creating the most personal wealth in America."

Between 1978 and 2013, the average compensation for CEOs at the biggest 350 companies in the US increased by 937 percent. That whopping gain didn’t happen because CEOs are more talented today than they used to be — it’s because we try to incentivize people in much the same way we did before the 1960s transformation.

“I think it’s a huge fallacy that these CEOs are highly motivated by extra compensation,” Martin say. “All the CEOs I work with say, ‘They’re paying me a ridiculous amount.’”

If you give someone a physical task, like moving rocks, and offer to pay them more for moving more rocks, they’ll do it. But if the person you’re dealing with is doing a mental task rather than a physical one, more money actually serves as a disincentive and hinders problem-solving. “It freaks you out,” Martin says.

“The value of monetary incentive compensation is vastly, vastly overestimated,” he believes. “If you shrunk in half the CEO compensation in America, there would be absolutely no diminution of the quality of management.” Plus, he says, “they wouldn’t complain.”

We’re not so sure about that last bit, but hey, it’s worth a shot.

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's Innovation Hub with Kara Miller.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!