Entrepreneurs around the world love this Soviet-era storytelling game

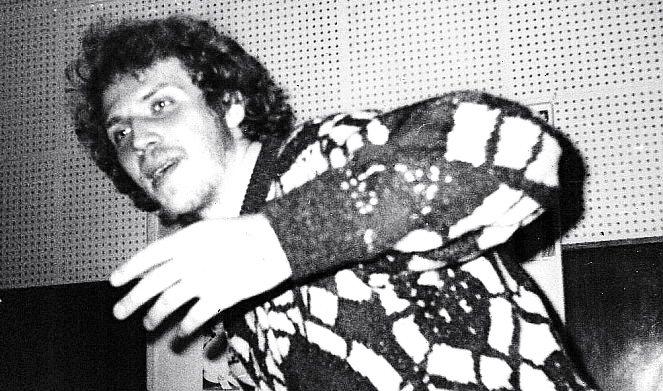

A tense moment during a game of "Mafia" in Kiev, Ukraine.

The storytelling parlor game “Mafia” crosses borders, transcends culture and bridges the language divide in ways you’d never expect.

There are no game boards or joysticks involved in Mafia — just words — and a setup that’s probably as old as human settlement: An uninformed majority of civilians against an informed minority, the Mafia. One side has power in numbers, the other has the power of knowledge.

Since 1987, Mafia has become a television series in Latvia, a World Championship event in Las Vegas and a training tool for the Russian security services. But I was still surprised to learn that Mafia was actually invented in the Soviet Union by Dimitry Davidoff, then a psychology graduate student at Moscow State University.

Davidoff tells me that even behind the Iron Curtain, he never doubted Mafia would become a global hit. In his day, games that were popular in the Soviet Union were all based on the idea of “us” vs. “them.” But in Mafia, as in real life, we ordinary civilians have no idea who the real enemies are — or whether the enemy is an enemy at all.

It turns out he struck a universal nerve. And once you get the hang of the rules, it’s also wicked fun.

But for today’s global entrepreneurs, Mafia has become much more than a game. “I think I use it all the time in real life," says Sam Lundin, who founded a website named Vimbly that helps New Yorkers find cool and adventuresome activities. He even hosts as monthly Mafia meetup.

Lundin says he's drawing on his Mafia skills "anytime there’s any kind of negotiation or problem-solving scenario going on, or someone is either bluffing or not bluffing in a business environment. Are they really telling the full story? Are they not?”

Sam was born in America, but he’s in the minority at a recent meetup. Most of the players are from China, Russia, South America or one of the many other places where Mafia is being put to strategic use. That includes Ukraine’s capital, Kiev.

“I believe in Kiev we have maybe 30 or 50 clubs. Maybe even more,” says Eugene Bazhenov. He started an English-language Mafia club back in 2010, and it immediately caught on with Ukrainians.

“The initial motivation is, of course, to improve English. But then they get addicted to the game because it’s really fun to play," Bazhenov says. People have even found dates — and spouses — through the club. "It’s a really good place to meet people, whatever your purpose is.”

As for Eugene’s purpose? “At that time I was working for a company and I wanted to have my own business, but I didn’t have network, I didn’t have money to start the business. So it was totally nothing," he says.

Nothing, that is, but a bunch of people crazy about Mafia, which is actually how Eugene achieved his goal. He ended up creating two companies with the help of expat Mafia players, one from Denmark, the other from Australia. Today, most of his closest friends, he tells me, are foreigners he met through the club.

It turns out, pretending to kill one another can really bring people together.

Meanwhile, back at Lundin's Mafia meetup, a Chinese woman named Joy is killing it — pun totally intended — for the civilians, picking off Mafia one by one.

She keeps insisting her English isn’t very good, but she's had a lot of practice at the game. About six years ago, Mafia — or the “Killer Game,” as it’s known there — became huge in China. Dozens of brick-and-mortar clubs sprang up across the country, complete with high-tech screens and audio systems blasting sound effects — all of which are completely unnecessary, given this is purely a storytelling game.

“They were like, ‘We have to deal with people we are not at all familiar with. We sometimes have to convey a particular message to our customers, or to our clients, and you sort of have to sometimes pretend to be someone else in these settings.’” Lindtner says.

Playing Mafia wasn't just a way to hone those skills: It was a great way to establish a competitive advantage. “These were skills they believed were utterly necessary in Chinese society, in international business relationships, and they were also saying that these were skills that would distinguish them from other people in China," Lindtner explains.

These kinds of concerns weren't on Dimitry Davidoff's radar when he created Mafia. Having grown up in the Soviet Union, the thought of a business application for the game never crossed his mind.

He actually designed Mafia in part as a means of understanding the bloody history of the Communist regime: Change the word Mafia to KGB, and the game becomes a metaphor for the Stalin era, where anyone could be an informant and a lot of innocent civilians get killed.

But 25 years later, Davidoff is now living in the United States and he’s made a business out of Mafia. He licenses it for various uses, and even served as a consultant for a Mafia movie that will be released next year in Russia.

The youthful version of himself that invented the game back in the Soviet era might even point at the Dmitry Davidoff of today and call him “Mafia.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?