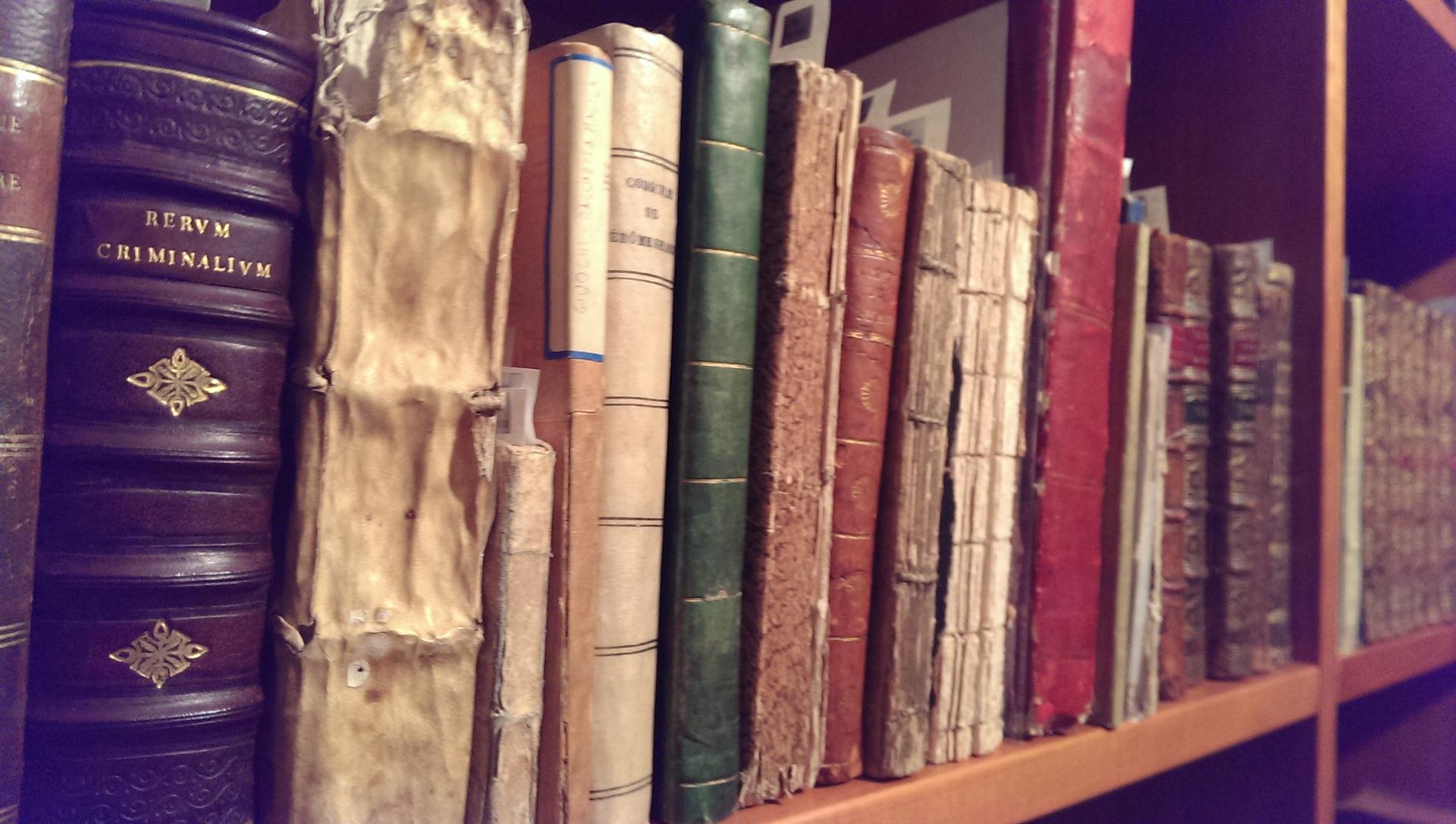

Some of the rarest books about magic and deception are accessible to the public at the Conjuring Arts Research Center in New York City.

Acquiring the esoteric knowledge necessary to become a good magician has never been easy. Some magicians only share their techniques with their protégés. Others take their secrets and tricks with them to their graves.

Then there’s Harry Houdini, who liked to scorch the magical earth behind him by publishing the mechanics of an act after he was done with it, deliberately shriveling the market for his imitators.

But one particular institution helps modern magicians get on the right path. The fifth floor of a non-descript high-rise in midtown Manhattan may not be the first place you would go in search of magic, but that’s exactly where one of the rarest repositories of magical literature in the world is housed — the Conjuring Arts Research Library.

“I wanted a place that was available for anyone with an appointment, to be able to come in and find some of the rarest material — the things that you couldn’t find, almost anywhere else in the world,” says Bill Kalush, the founder of Conjuring Arts Research Center.

You’ll find rare magic books elsewhere, he explains, but many of those books sit on the shelves unread, in their original Italian or Persian or French. Conjuring Arts doesn’t just collect books — it translates them.

“The first person we hired was this amazing woman who translates from five or six languages into English. So we’re making these early books in other languages from other cultures and other parts of the world, accessible to English-speaking readers,” Kalush says.

Ths includes what's believed to be the very first book of magic — the 15th century "De viribus quantitates" by Luca Pacioli, which the library is translating from Latin.

Of course, magic means different things to different people, from chanting Silencio while waving your Harry Potter wand to ventilating a voodoo doll.

Kalush keeps it simple: “We’re interested in deception” — meaning literature on mentalism, card magic and cryptography, as well as books on gambling, and cheating at cards and at dice.

But as with all things magic, what you see isn’t ever what you get.

“Sometimes books masquerade as other objects, other objects masquerade as books.”

Kalush shows me an Italian devotional book written by Horatio Galasso in 1617. Every page is filled with pictures of saints arranged in a simple grid. I am asked to pick one of the images, without saying what it is. Bill flips a few pages and asks me a seemingly unrelated question:

“You’re thinking of St. Rocco?”

“Yeah, how’d you do that?” I ask.

“This is a mind-reading book; it’s not even really a book. It’s a prop that was meant to be used to read minds,” he says.

The practice of magic itself seems like a gateway drug to the study of its history. Kalush started off as a magician himself before turning to serious scholarship. And now Conjuring Arts is helping both magicians and historians alike by putting the dark arts online.

“We’ve got about 2.5 million unique pages that we’ve scanned so far, and it represents material from the 15th century to things that have just come out in the last month,” he says.

The library’s database is called Ask Alexander — a nod to Claude Alexander Conlin, an infamous mentalist popular in the 1920s, who claimed to be able to “know, see and tell all.”

The database is changing how magicians craft their acts.

“People think you go in a magic shop, buy a trick and then that’s it,” says Munich-based magician Thomas Fraps. He’s never visited Conjuring Arts, but he asked Alexander to research a 100-year-old trick called “The Educated Goldfish,” in which live goldfish drag scrabble-like letters to the surface of an aquarium to spell words called out by the audience.

“I always liked that but I had never seen it performed because it’s actually rather complicated. You would need a huge area underneath the stage and 26 wires and a guy underneath the stage. It was really, really complicated,” Fraps says.

Ask Alexander helped Fraps resurrect a more portable version of The Educated Goldfish for his own live act.

It’ll take a while before it’s all online — the library contains more than five million documents, including one-of-a-kind items that haven’t been recorded in any magic literature or bibliographies.

“We probably have in the neighborhood of 20,000 magician’s letters; magicians trading secrets and gossip. And we’ve gone through, cataloged and digitized about 7,000 so far of our collection,” Kalush says.

The one thing you probably won’t spot here, though, is an actual magician: Kalush is careful to protect the identity of the world famous conjurers who’ve made the library their clubhouse.

“We try to keep it as mysterious as possible and we do have an awful lot of interesting people visit,” he says. “If I were to tell you all about it, I think that our source of interesting people flowing through the door might be cut off."

Fair enough.