Getting Asian immigrants in the US to vote means breaking the language barrier

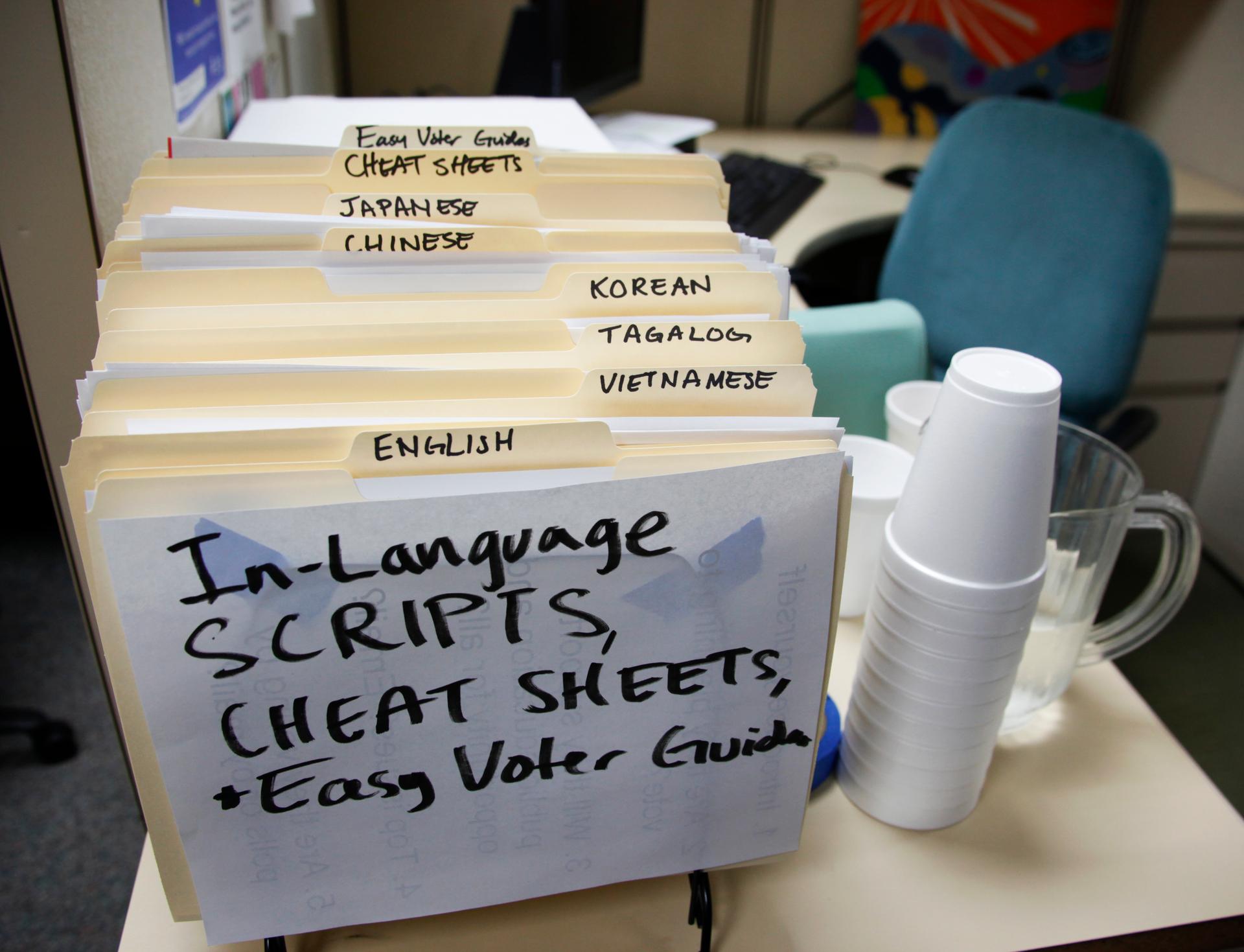

Volunteers with Asian Americans Advancing Justice, an Los Angeles-based non-profit, work the phones to get Asian-American voters to the polls in California. The phone bank is part of the "Your Vote Matters" campaign, an effort to get 30,000 infrequent voters to cast their ballots.

A Chinese restaurant during the lunch rush isn’t the first place you’d expect to find a campaign event. But here's Republican congressional candidate Carl DeMaio, working the banquet room at the China Max restaurant in San Diego and answering questions from local Chinese and Vietnamese reporters.

“The Asian community, all communities, want the same thing,” DeMaio tells a small group of supporters. “We should be focused on what unites us, not divides us.”

The event is one of several DeMaio has held targeting Asian Americans. It’s not a voting bloc that Republicans historically court, but DeMaio is in a dead heat against incumbent Democrat Scott Peters. He knows there are plenty of independents in this room who might help him win this election.

“This is a toss-up seat," says Jacqui Nguyen. "It’s registered one-third Republican, one-third Democrat, one-third decline-to-state. Within that registration, there’s between 18 to 20 percent Asian American votes out there. That’s a lot of votes that both candidates can try to grab.”

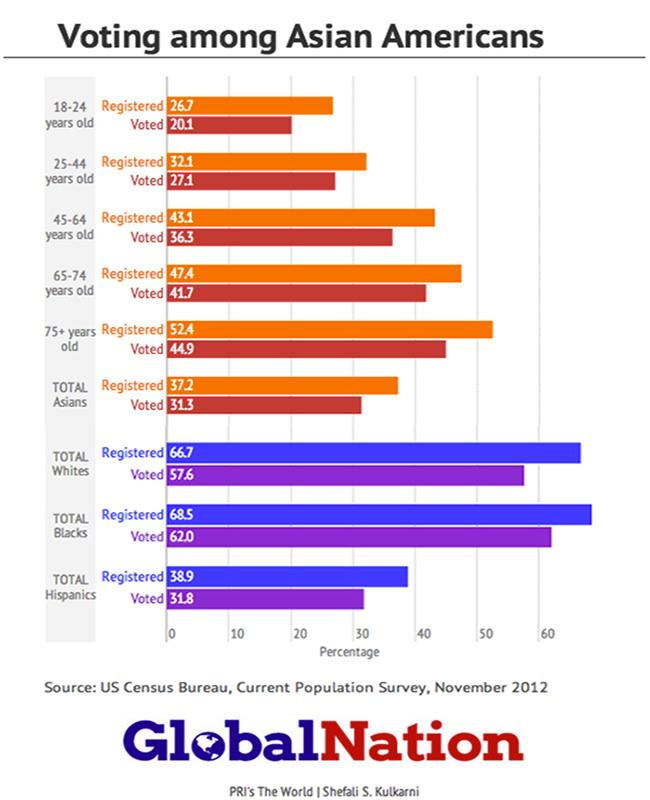

Asian and Pacific Islanders now represent nearly nine million eligible voters nationwide, the fastest growing minority group in the country. The voting bloc has doubled in size in the last decade, and there’s an effort to get more of them out to vote.

That's why the Republican National Committee has hired Nguyen and two other full-time staffers in California to reach out to Asians and Pacific Islanders. Similar staffers, ones plugged into Asian communities, have also been hired in Colorado, Texas, New York and Virginia. The effort is a direct response to the 2012 presidential election, when Asian Americans overwhelmingly voted for President Obama.

Getting these votes out means overcoming cultural differences; many Asian Americans have never voted at all, even in their native countries.

“They come from countries where democracy, this kind of a voting process, isn’t part of their natural culture,” says Tanzila Ahmed ofAsian Americans Advancing Justice, a civic enagement group. “They have to learn about what it means to be a voter. It’s a very new process for them.”

But more than anything else, it's about breaking breaking down the language barrier. More than a third of Asian-American voters aren’t fluent in English, and they don’t share a common language. That makes Asian American voters hard to reach for many candidates.

“It’s too difficult for them to translate the mailers, it’s too difficult to try and find volunteers that speak their language," Ahmed says.

She points out that that “a lot of what it means to be engaged in the political process in the US is getting materials from candidates and campaigns because they’re trying to win your vote." Many Asian Americans simply don't get that opportunity at all.

So Ahmed is running a phone bank that uses young student volunteers to answer questions about voting in 17 different languages, including Vietnamese, Bengali, Urdu and Mandarin. The goal is to get roughly 30,000 registered voters who don't usually go to the polls to cast their ballots.

Ahmed says she’s noticed that engaging potential voters can be as simple as knowing a greeting in their native language. She often uses an Arabic greeting to engage Muslim voters, and she also likes to share her own story with potential voters.

A few months after September 11, FBI agents came to her parents’ home in California to question her cousin, a young Muslim American. Ahmed says her cousin was singled out because of her family's religion, even though they stopped attending their mosque and wore patriotic pins to ease suspicions.

She remembers what her mom said back then: “She said to me, ‘It doesn’t matter how long I’ve been in this country, or that I have my citizenship. I’m always going to be treated as a second-class citizen,'” Ahmed says. “That’s a message I take with me whenever I do voter engagement work.”

As Ahmed becomes more politically active, she’s seen the tide turn. California’s online voter registration site added eight new Asian languages this year, including Hindi, Tagalog and Thai.

That may help increase participation in races this November, but the real test will come in two years. With a presidential election on the ballots, candidates will amp up efforts to bring out historically overlooked voters who, hopefully, will influence how the country chooses its next leader.