The Tiananmen Square story was historic for the international news business — but it was also a fluke

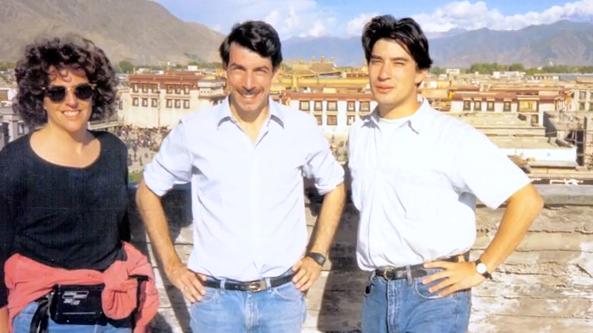

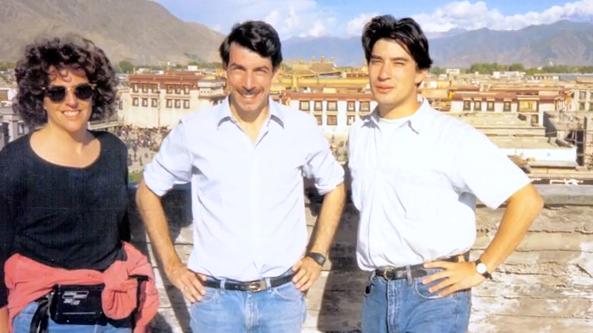

A group of journalists supports the pro-democracy protest in Tiananmen Square, Beijing May 17, 1989.

Americans who were at least old enough to be in grade school during the spring of 1989 will probably remember watching the events leading up to the Tiananmen Square crackdown play out on live television. It was a hugely important story for the international news media, and for broadcasters in particular.

And that had a lot to do with an accident of history.

“It's one of the great ironies of the Tiananmen story,” says Mike Chinoy, who was CNN's Beijing bureau chief in 1989. Journalists did not have to jump on planes in a rush to cover the protests in China, because they were already there.

“It was only because the Chinese were hosting Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev,” Chinoy says.The Gorbachev summit in Beijing was planned for mid-May of 1989. Its aim was to put an end to 30 years of Sino-Soviet animosity. And this is what prompted Beijing to allow so many international journalists into China.

“It was only because the Chinese were hosting Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev,” Chinoy says.The Gorbachev summit in Beijing was planned for mid-May of 1989. Its aim was to put an end to 30 years of Sino-Soviet animosity. And this is what prompted Beijing to allow so many international journalists into China.

“The Chinese were so excited about this summit, they agreed to let CNN … and other networks bring in satellite dishes, microwave transmitters, lots of extra camera crews,” Chinoy says. “And then, the protesting students literally stole the stage on which this Gorbachev summit, pomp and ceremony was to have been played out.”

As the Wall Street Journal reported on the day of the Soviet leader's arrival in Beijing, “The timing of Mr. Gorbachev’s visit puts the Chinese government in a bind. Had the ceremony been held at Tiananmen Square, the hunger-striking students and thousands of onlookers were likely to greet Mr. Gorbachev as a savior — implicitly criticizing China’s lack of political reform.”

Ultimately, Gorbachev's welcoming ceremony in the square was cancelled. But all those cameras were still there, and rolling — but instead of covering the Sino-Soviet summit, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators demanding political change became the biggest news story around the world.

“For the Chinese leadership, this was an extraordinary humiliation,” Chinoy says. “And to [Chinese leader] Deng Xiaoping in particular. This was going to be the crowning diplomatic achievement of his career.”

Chinoy says, “We'll never really know all of the factors that went into their decision to declare martial law and crack down, but I certainly suspect that the intense humiliation and embarrassment … was one of the factors.”

A 10-part documentary called “Assignment: China,” produced by Chinoy, covers the history of American journalists in China from the 1940s to the present. And the episode called “Tiananmen Square” gets into some riveting details of how the reporters who were there covered the story of a lifetime.

The film recounts how Chinese officials showed up at CNN's headquarters at the Sheraton Hotel to shut down the network. Staff tried to stall by demanding that officials deliver the order in writing. When the papers were produced, CNN turned a live camera on the scene so viewers could watch how the Chinese government was moving to put a lid on the story of the demonstrations.

When the violent crackdown began on the night of June 3, some journalists risked arrest, injury or worse to keep reporting the story from close up. Chinoy's documentary includes interviews with several reporters who stayed in or near Tiananmen Square through the bloodiest hours of the army's assault.

Sometimes, the foreign media got things wrong in 1989. Many correspondents believed mistakenly that the Chinese government would not resort to such brutal tactics and that students were sure to win their fight for fundamental political change.

News reports at the time, Chinoy says, left the wrong impression with audiences back home by oversimplifying the students' demands, and describing them in shorthand as “pro-democracy” demonstrations. US journalists even contributed to rumors — later proven unfounded — that violence was breaking out between rival Chinese army units.

“Assignment – China: Tiananmen Square” gets into all of this, and it includes some frank self-criticism from journalists who covered those events.

“The job of the foreign media is to tell the story of what happened,” Chinoy says. “And for all the things that one can criticize the media for, … I think, on balance, the journalists did a pretty good job.”

And the story they were covering, he adds, “as my old Chinese history professor said right after June 4, … 'that is a date that will haunt authoritarian governments in China for years.”

Americans who were at least old enough to be in grade school during the spring of 1989 will probably remember watching the events leading up to the Tiananmen Square crackdown play out on live television. It was a hugely important story for the international news media, and for broadcasters in particular.

And that had a lot to do with an accident of history.

“It's one of the great ironies of the Tiananmen story,” says Mike Chinoy, who was CNN's Beijing bureau chief in 1989. Journalists did not have to jump on planes in a rush to cover the protests in China, because they were already there.

“It was only because the Chinese were hosting Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev,” Chinoy says.The Gorbachev summit in Beijing was planned for mid-May of 1989. Its aim was to put an end to 30 years of Sino-Soviet animosity. And this is what prompted Beijing to allow so many international journalists into China.

“It was only because the Chinese were hosting Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev,” Chinoy says.The Gorbachev summit in Beijing was planned for mid-May of 1989. Its aim was to put an end to 30 years of Sino-Soviet animosity. And this is what prompted Beijing to allow so many international journalists into China.

“The Chinese were so excited about this summit, they agreed to let CNN … and other networks bring in satellite dishes, microwave transmitters, lots of extra camera crews,” Chinoy says. “And then, the protesting students literally stole the stage on which this Gorbachev summit, pomp and ceremony was to have been played out.”

As the Wall Street Journal reported on the day of the Soviet leader's arrival in Beijing, “The timing of Mr. Gorbachev’s visit puts the Chinese government in a bind. Had the ceremony been held at Tiananmen Square, the hunger-striking students and thousands of onlookers were likely to greet Mr. Gorbachev as a savior — implicitly criticizing China’s lack of political reform.”

Ultimately, Gorbachev's welcoming ceremony in the square was cancelled. But all those cameras were still there, and rolling — but instead of covering the Sino-Soviet summit, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators demanding political change became the biggest news story around the world.

“For the Chinese leadership, this was an extraordinary humiliation,” Chinoy says. “And to [Chinese leader] Deng Xiaoping in particular. This was going to be the crowning diplomatic achievement of his career.”

Chinoy says, “We'll never really know all of the factors that went into their decision to declare martial law and crack down, but I certainly suspect that the intense humiliation and embarrassment … was one of the factors.”

A 10-part documentary called “Assignment: China,” produced by Chinoy, covers the history of American journalists in China from the 1940s to the present. And the episode called “Tiananmen Square” gets into some riveting details of how the reporters who were there covered the story of a lifetime.

The film recounts how Chinese officials showed up at CNN's headquarters at the Sheraton Hotel to shut down the network. Staff tried to stall by demanding that officials deliver the order in writing. When the papers were produced, CNN turned a live camera on the scene so viewers could watch how the Chinese government was moving to put a lid on the story of the demonstrations.

When the violent crackdown began on the night of June 3, some journalists risked arrest, injury or worse to keep reporting the story from close up. Chinoy's documentary includes interviews with several reporters who stayed in or near Tiananmen Square through the bloodiest hours of the army's assault.

Sometimes, the foreign media got things wrong in 1989. Many correspondents believed mistakenly that the Chinese government would not resort to such brutal tactics and that students were sure to win their fight for fundamental political change.

News reports at the time, Chinoy says, left the wrong impression with audiences back home by oversimplifying the students' demands, and describing them in shorthand as “pro-democracy” demonstrations. US journalists even contributed to rumors — later proven unfounded — that violence was breaking out between rival Chinese army units.

“Assignment – China: Tiananmen Square” gets into all of this, and it includes some frank self-criticism from journalists who covered those events.

“The job of the foreign media is to tell the story of what happened,” Chinoy says. “And for all the things that one can criticize the media for, … I think, on balance, the journalists did a pretty good job.”

And the story they were covering, he adds, “as my old Chinese history professor said right after June 4, … 'that is a date that will haunt authoritarian governments in China for years.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!