To get the autographs of top world leaders, you need commitment, courage and chutzpah

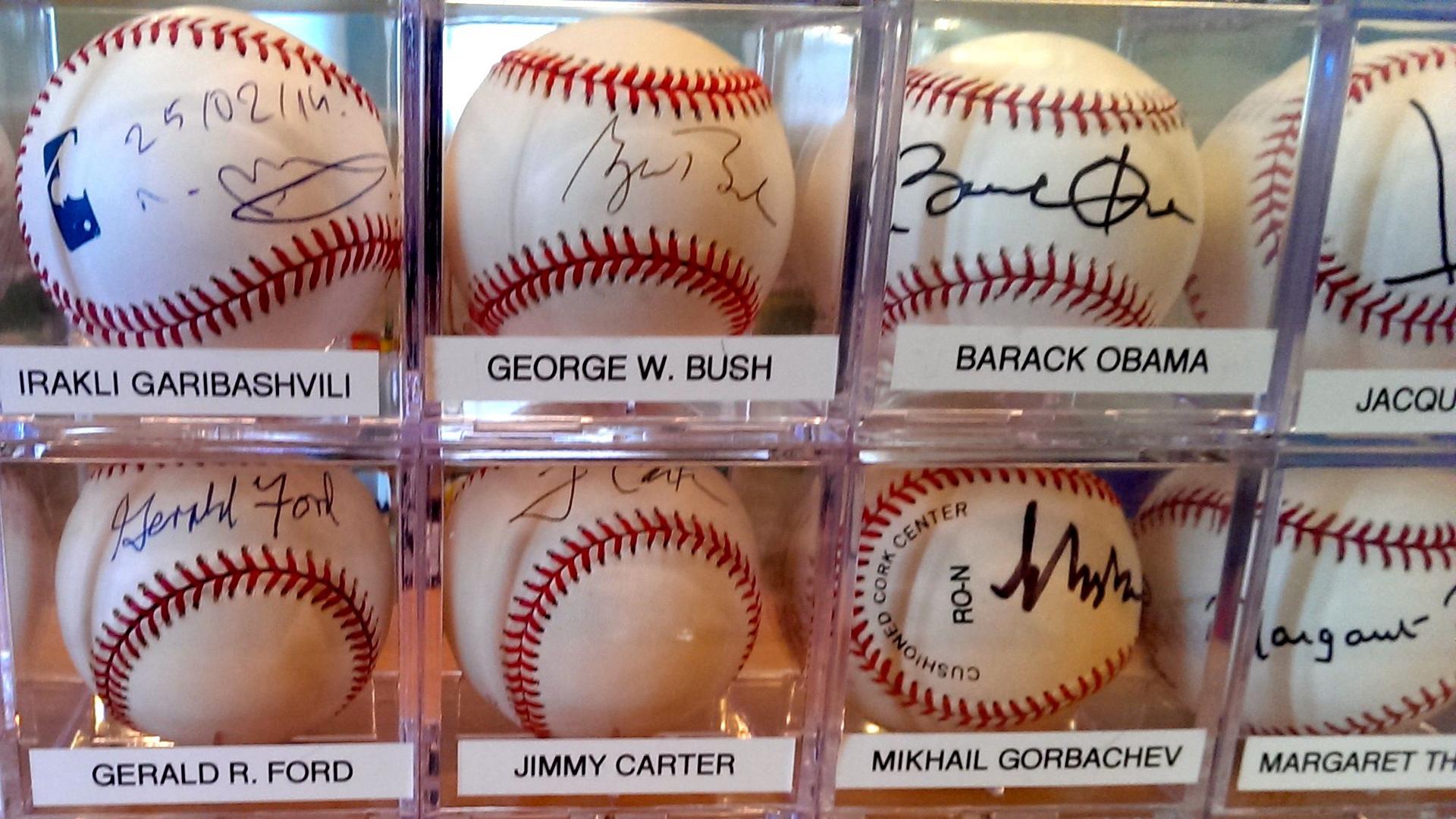

These are some of the top names from the autograph collection of Randy Kaplan. He launched his collection in 1996, with the autograph of Bill Clinton, and has collected 130 autographed baseballs to date.

I’m always on the look out for attention-grabbing stats, so when I heard the most valuable autograph of a living person in the world belonged to Fidel Castro, I thought — there’s a cool business story.

But as soon as I started talking to this elite group of collectors — the autograph hunters who vie for the attention of the world’s most famous, elusive and often, notorious leaders — I realized this piece wasn’t going to be about numbers: it was about people. In the words of autograph hunter Randy Kaplan, “You have to be cut from a special mold to be a collector that’s successful in getting in-person autographs like this.”

Kaplan has been collecting the signatures of world leaders on baseballs since 1996. He was the one who introduced me to the idea of autographing-as-blood-sport.

Kaplan schmoozed Hamid Karzai’s security detail for his autograph and smooth-talked his way into then-president of Nigeria General Olusegun Obasanjo’s hotel room. He even mastered phonetic Russian well enough to convince Gorbachev’s bodyguards the baseball in his hand wasn’t a bomb.

“You either have it, or you don’t,” Kaplan told me. “You have to plan everything three steps ahead. You have to do all your research. You have find out who their defense secretary is, anyone who’s going to be with them. Most importantly, as a collector, you have to be prepared for the unprepared; I never go anywhere without at least a dozen baseballs on me, at all times. “

By now I’m feeling like autograph hunting requires as much specialized gear as regular hunting, like a 12 pocket flak-jacket to hold the baseballs. But according to Kaplan, your memory has to be even stronger than your back.

“My son and I were in the city during UN week, and I noticed some state department cars outside of a Turkish restaurant on 2nd Avenue on the Upper East Side," he recalls. "So naturally we went over there together, and sure enough, who’s walking out but the president of Kosovo — could not believe it! — Atifete Jahjaga.”

“My son and I were in the city during UN week, and I noticed some state department cars outside of a Turkish restaurant on 2nd Avenue on the Upper East Side," he recalls. "So naturally we went over there together, and sure enough, who’s walking out but the president of Kosovo — could not believe it! — Atifete Jahjaga.”

I can understand walking into a falafel joint and spotting Obama, or even Russian President Vladimir Putin — but the president of Kosovo?

Not every president walking out of a Turkish restaurant gives Kaplan his autograph, though. That rejection, he admitted in an email, can trigger a mini-depression. But as much as he wants to get those autographs, he's not indiscriminate about whose autograph he seeks.

“There are people I would not want to have as a part of my collection,” Kaplan says. “Anybody who’s a mass-murderer, somebody who’s indicted on crimes-against-humanity — I try to avoid those people. The lust is still there to try and get them, but there’s also a barrier up saying ‘No, I don’t want them in my collection.’ I want it to be people that I’m proud of.”

Fidel Castro’s signature would make Kaplan proud, he says. Getting El Comandante’s autograph on a ball is a kind of holy grail for Kaplan. He’s been trying to get it for years, without success.

If only Kaplan had grown up in a Communist country, he’d have a lot more luck. Hungarian collector Zoltan Marian had a foreign ministry official get a signed photograph from Castro back in 1972, when Castro visited Budapest for the first and only time.

“Yes, I am proud of Fidel Castro because I know he is very, very difficult,” Marian says. “Since 1972, I tried to write him once again, but I only received a copy of a fax.”

Because Zoltan is agnostic when it comes to a leader’s politics, his collection of more than 1300 signed photos includes some truly chilling names: Pinochet, Mobutu Sese Seko, “Papa Doc” Duvalier, Saddam Hussein. But the standouts are autographs so rare dealers have trouble even putting a price on them: the dynastic leaders of North Korea.

With help from his own Communist government, Zoltan managed to get Kim Il Sung’s signed photo. But for years he had no such luck with Kim’s son. Finally Zoltan sent Kim Jong Il a copy of the very same photo Kim the elder had signed years before, hoping that might convince him to send Zoltan his autograph. Instead two guys from the North Korean embassy showed up at his door. Somehow, over the course of a very tense tea, Zoltan managed to win them over.

“I had to wait for a long time,” Zoltan says. “About for a year or more, but finally I received a signed photo of the Dear Leader.”

Zoltan’s collection includes autographs of many such Cold War all-stars — signatures that Western collectors have a lot of trouble getting (unless they buy them on eBay).

But autograph hunting from a Communist Country wasn’t always easier. “Sometimes I was invited to the police station and they told me: Do not write those letters to these, these and that person,” Zoltan explains.

Back in the '70s, the Hungarian police even warned Zoltan to stop writing to Alexander Dubček, the former Communist leader of neighboring Czechoslovakia. Dubček was responsible for the Prague Spring, but was under house arrest.

Zoltan kept writing anyway. He didn’t care. What he did was address his letter to Dubček's wife, under her maiden name. Eventually, he got his man.

The World in Words podcast is on Facebook and iTunes.

I’m always on the look out for attention-grabbing stats, so when I heard the most valuable autograph of a living person in the world belonged to Fidel Castro, I thought — there’s a cool business story.

But as soon as I started talking to this elite group of collectors — the autograph hunters who vie for the attention of the world’s most famous, elusive and often, notorious leaders — I realized this piece wasn’t going to be about numbers: it was about people. In the words of autograph hunter Randy Kaplan, “You have to be cut from a special mold to be a collector that’s successful in getting in-person autographs like this.”

Kaplan has been collecting the signatures of world leaders on baseballs since 1996. He was the one who introduced me to the idea of autographing-as-blood-sport.

Kaplan schmoozed Hamid Karzai’s security detail for his autograph and smooth-talked his way into then-president of Nigeria General Olusegun Obasanjo’s hotel room. He even mastered phonetic Russian well enough to convince Gorbachev’s bodyguards the baseball in his hand wasn’t a bomb.

“You either have it, or you don’t,” Kaplan told me. “You have to plan everything three steps ahead. You have to do all your research. You have find out who their defense secretary is, anyone who’s going to be with them. Most importantly, as a collector, you have to be prepared for the unprepared; I never go anywhere without at least a dozen baseballs on me, at all times. “

By now I’m feeling like autograph hunting requires as much specialized gear as regular hunting, like a 12 pocket flak-jacket to hold the baseballs. But according to Kaplan, your memory has to be even stronger than your back.

“My son and I were in the city during UN week, and I noticed some state department cars outside of a Turkish restaurant on 2nd Avenue on the Upper East Side," he recalls. "So naturally we went over there together, and sure enough, who’s walking out but the president of Kosovo — could not believe it! — Atifete Jahjaga.”

“My son and I were in the city during UN week, and I noticed some state department cars outside of a Turkish restaurant on 2nd Avenue on the Upper East Side," he recalls. "So naturally we went over there together, and sure enough, who’s walking out but the president of Kosovo — could not believe it! — Atifete Jahjaga.”

I can understand walking into a falafel joint and spotting Obama, or even Russian President Vladimir Putin — but the president of Kosovo?

Not every president walking out of a Turkish restaurant gives Kaplan his autograph, though. That rejection, he admitted in an email, can trigger a mini-depression. But as much as he wants to get those autographs, he's not indiscriminate about whose autograph he seeks.

“There are people I would not want to have as a part of my collection,” Kaplan says. “Anybody who’s a mass-murderer, somebody who’s indicted on crimes-against-humanity — I try to avoid those people. The lust is still there to try and get them, but there’s also a barrier up saying ‘No, I don’t want them in my collection.’ I want it to be people that I’m proud of.”

Fidel Castro’s signature would make Kaplan proud, he says. Getting El Comandante’s autograph on a ball is a kind of holy grail for Kaplan. He’s been trying to get it for years, without success.

If only Kaplan had grown up in a Communist country, he’d have a lot more luck. Hungarian collector Zoltan Marian had a foreign ministry official get a signed photograph from Castro back in 1972, when Castro visited Budapest for the first and only time.

“Yes, I am proud of Fidel Castro because I know he is very, very difficult,” Marian says. “Since 1972, I tried to write him once again, but I only received a copy of a fax.”

Because Zoltan is agnostic when it comes to a leader’s politics, his collection of more than 1300 signed photos includes some truly chilling names: Pinochet, Mobutu Sese Seko, “Papa Doc” Duvalier, Saddam Hussein. But the standouts are autographs so rare dealers have trouble even putting a price on them: the dynastic leaders of North Korea.

With help from his own Communist government, Zoltan managed to get Kim Il Sung’s signed photo. But for years he had no such luck with Kim’s son. Finally Zoltan sent Kim Jong Il a copy of the very same photo Kim the elder had signed years before, hoping that might convince him to send Zoltan his autograph. Instead two guys from the North Korean embassy showed up at his door. Somehow, over the course of a very tense tea, Zoltan managed to win them over.

“I had to wait for a long time,” Zoltan says. “About for a year or more, but finally I received a signed photo of the Dear Leader.”

Zoltan’s collection includes autographs of many such Cold War all-stars — signatures that Western collectors have a lot of trouble getting (unless they buy them on eBay).

But autograph hunting from a Communist Country wasn’t always easier. “Sometimes I was invited to the police station and they told me: Do not write those letters to these, these and that person,” Zoltan explains.

Back in the '70s, the Hungarian police even warned Zoltan to stop writing to Alexander Dubček, the former Communist leader of neighboring Czechoslovakia. Dubček was responsible for the Prague Spring, but was under house arrest.

Zoltan kept writing anyway. He didn’t care. What he did was address his letter to Dubček's wife, under her maiden name. Eventually, he got his man.