Scarred by childbirth, mothers are finding help to heal and start over

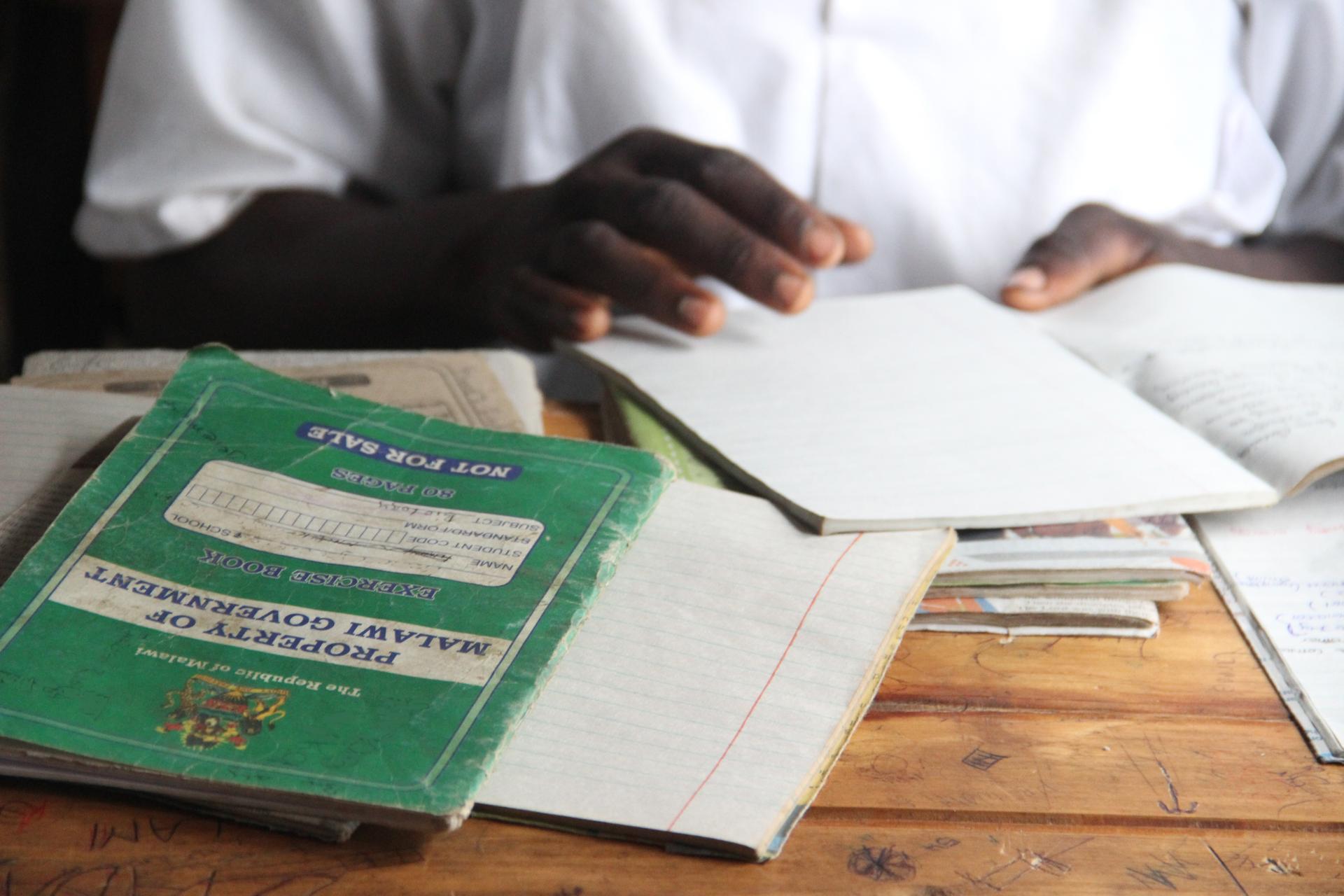

“Jennifer” opens her notebook during physics class at a school outside Lilongwe, Malawi. After undergoing fistula surgery, she re-enrolled in school and is now completing ninth grade at age 25.

Jennifer grew up in a rural village in the African nation of Malawi. She loved learning, but at 16, she dropped out of school to get married. A few months later, she became pregnant.

When Jennifer (not her real name) went into labor, she was at home — a small, thatched-roof hut with dirt floors. It was the middle of the night. “We had to wait until daytime to go to the hospital,” she said. It was too dark to walk, and she had no transportation.

Early the next morning, she got a ride from a neighbor. They traveled more than an hour along a bumpy dirt road, past fields of corn and tobacco.

When Jennifer finally arrived at the hospital, the nurses noticed a problem — her baby was in the wrong position. She had never received prenatal care, so the problem had gone undetected. She had already been in labor for over eight hours, and she stayed in labor for the next 16 hours.

“It took so much time,” she said. “At the end of it all, I eventually delivered.”

But the baby had died. Jennifer was devastated.

The next day, she noticed another problem. She had become incontinent. “I was leaking urine constantly,” she said.

Jennifer had developed an obstetric fistula — a hole in the wall of the vagina caused by pressure during an obstructed delivery.Jennifer’s bladder was also damaged, creating a connection between her urinary and vaginal tracts. In her case, the fistula was likely caused by the baby’s head, and her young age may have been a contributing factor.

Social consequences

Obstetric fistula affects hundreds of thousands of women in sub-Saharan Africa. For many, it is far more than a physical ailment. It can turn them into outcasts.

She continued living that way for years. She said she hated her life.

Then she met Dr. Jeffrey Wilkinson, an American surgeon from the University of North Carolina. He worked with the Freedom from Fistula Foundation to found a surgical center at Bwaila District Hospital in Malawi’s capital, Lilongwe. The center is dedicated to treating fistula, which can be corrected with a relatively simple operation that takes as little as ten minutes. Wilkinson performs up to 25 such surgeries per week at the center.

After years of operating on fistula patients, Wilkinson realized something. “The surgery is absolutely necessary,” he said, “but it’s only the beginning of their recovery.”

Wilkinson said many of the women he sees have been suffering from fistula for years and don’t have a social support network. Most have been ostracized by their families, and many have divorced. They often struggle to find work, and most are illiterate.

Wilkinson and his colleagues had an idea: What if they could help educate these women during the three-week recovery from surgery? “We wanted to leave them a little better off than they would otherwise be,” he said.

He and his team hired teachers to give basic math and reading lessons, and to teach women how to sew and weave. They set up a mock market, inside the clinic, to help women develop sales and negotiating skills.

And in some cases, the clinic raised money for women to go back to school.

A new beginning

Jennifer is a case in point. After developing a fistula at age 17 and undergoing surgery at 24, she is now 25 and has enrolled in ninth grade.

On a recent afternoon, she sat inside a two-room brick schoolhouse in a rural village outside of Lilongwe. She was surrounded by more than 75 other students, most of whom looked much younger than Jennifer. She took notes as a teacher gave a lesson on physics.

After class, Jennifer told me it was hard to go back to school.

“I was embarrassed because I’m so much older than everyone here,” she said. But she stuck with it, mainly because she wanted to improve her life. She also drew inspiration from other women at the fistula clinic who had returned to school.

Jennifer said she is getting good grades — mostly As and Bs — and is especially enjoying her science classes. None of her classmates know her age or her background. In fact, that is why she enrolled at this school — because it was close to her grandmother’s house, and nobody at the school knew her.

Now that doctors have fixed the problem that resulted from her trying to give birth, Jennifer said she feels like she has been reborn.

“I’m a happy person, a happy human being, because the problem that I [had] is gone,” she said.

Jennifer said she would like to get married again someday, and to have kids — both of which seemed impossible before the surgery.

For now, she just plans to focus on her schoolwork.

Jennifer grew up in a rural village in the African nation of Malawi. She loved learning, but at 16, she dropped out of school to get married. A few months later, she became pregnant.

When Jennifer (not her real name) went into labor, she was at home — a small, thatched-roof hut with dirt floors. It was the middle of the night. “We had to wait until daytime to go to the hospital,” she said. It was too dark to walk, and she had no transportation.

Early the next morning, she got a ride from a neighbor. They traveled more than an hour along a bumpy dirt road, past fields of corn and tobacco.

When Jennifer finally arrived at the hospital, the nurses noticed a problem — her baby was in the wrong position. She had never received prenatal care, so the problem had gone undetected. She had already been in labor for over eight hours, and she stayed in labor for the next 16 hours.

“It took so much time,” she said. “At the end of it all, I eventually delivered.”

But the baby had died. Jennifer was devastated.

The next day, she noticed another problem. She had become incontinent. “I was leaking urine constantly,” she said.

Jennifer had developed an obstetric fistula — a hole in the wall of the vagina caused by pressure during an obstructed delivery.Jennifer’s bladder was also damaged, creating a connection between her urinary and vaginal tracts. In her case, the fistula was likely caused by the baby’s head, and her young age may have been a contributing factor.

Social consequences

Obstetric fistula affects hundreds of thousands of women in sub-Saharan Africa. For many, it is far more than a physical ailment. It can turn them into outcasts.

She continued living that way for years. She said she hated her life.

Then she met Dr. Jeffrey Wilkinson, an American surgeon from the University of North Carolina. He worked with the Freedom from Fistula Foundation to found a surgical center at Bwaila District Hospital in Malawi’s capital, Lilongwe. The center is dedicated to treating fistula, which can be corrected with a relatively simple operation that takes as little as ten minutes. Wilkinson performs up to 25 such surgeries per week at the center.

After years of operating on fistula patients, Wilkinson realized something. “The surgery is absolutely necessary,” he said, “but it’s only the beginning of their recovery.”

Wilkinson said many of the women he sees have been suffering from fistula for years and don’t have a social support network. Most have been ostracized by their families, and many have divorced. They often struggle to find work, and most are illiterate.

Wilkinson and his colleagues had an idea: What if they could help educate these women during the three-week recovery from surgery? “We wanted to leave them a little better off than they would otherwise be,” he said.

He and his team hired teachers to give basic math and reading lessons, and to teach women how to sew and weave. They set up a mock market, inside the clinic, to help women develop sales and negotiating skills.

And in some cases, the clinic raised money for women to go back to school.

A new beginning

Jennifer is a case in point. After developing a fistula at age 17 and undergoing surgery at 24, she is now 25 and has enrolled in ninth grade.

On a recent afternoon, she sat inside a two-room brick schoolhouse in a rural village outside of Lilongwe. She was surrounded by more than 75 other students, most of whom looked much younger than Jennifer. She took notes as a teacher gave a lesson on physics.

After class, Jennifer told me it was hard to go back to school.

“I was embarrassed because I’m so much older than everyone here,” she said. But she stuck with it, mainly because she wanted to improve her life. She also drew inspiration from other women at the fistula clinic who had returned to school.

Jennifer said she is getting good grades — mostly As and Bs — and is especially enjoying her science classes. None of her classmates know her age or her background. In fact, that is why she enrolled at this school — because it was close to her grandmother’s house, and nobody at the school knew her.

Now that doctors have fixed the problem that resulted from her trying to give birth, Jennifer said she feels like she has been reborn.

“I’m a happy person, a happy human being, because the problem that I [had] is gone,” she said.

Jennifer said she would like to get married again someday, and to have kids — both of which seemed impossible before the surgery.

For now, she just plans to focus on her schoolwork.