Climate change talks now have human rights on the agenda

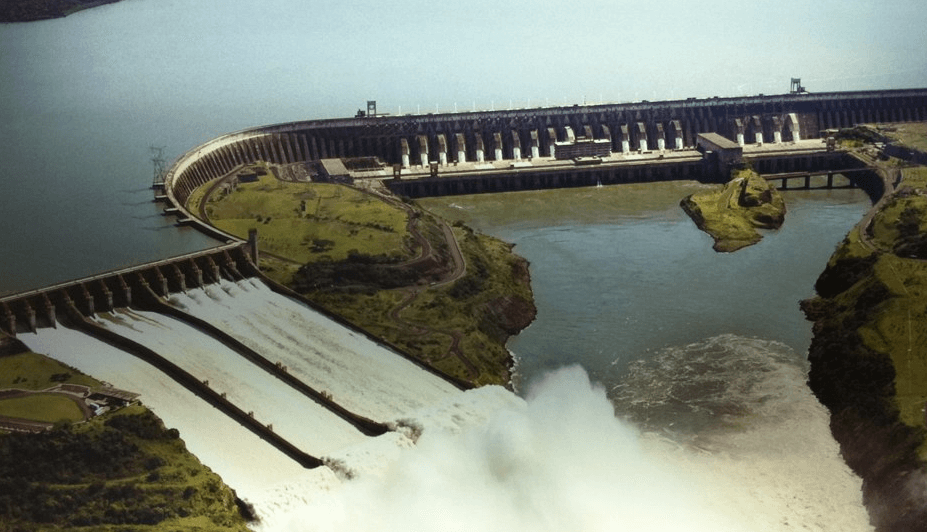

Many hydropower projects in South America, like this dam in Brazil, and poorer countries throughout the world are touted as a solution to climate change, providing “clean” energy. But they often displace local peoples from their land and cause other human rights problems.

The latest meeting of United Nations climate negotiators, known as COP 20, began December 1 in Lima, Peru with one agenda item higher on the list than usual: human rights.

There’s renewed optimism in the air at these talks, after the two mega-polluters, China and the US, agreed to substantial cuts in their emissions. Solid commitments of $10 billion have been made for the Green Climate Fund.

And there’s a new commitment, as well: to make human rights a guiding principle of any agreement, including agreements on green energy development and forest protection programs.

Marianne Lavelle, a science writer for The Daily Climate, says that a few years ago, most of the discussion around climate change centered on emissions cuts, timetables and “a whole lot of numbers.” But recently, she says, the talk has been “more about people, about social justice and human rights.”

“Poor countries and poor people around the world are most affected by climate change, but they are the people who have the least to do with the carbon emissions overload that we now are facing,” Lavelle says.

Human rights issues persist even around issues on which most parties agree — for example, reducing global deforestation and degradation. “This was really thought of as a win-win solution,” Lavelle says, “because the richer nations could invest in projects to preserve forests in poorer nations.” But some of these projects, like putting up palm oil plantations, are not preserving the forest as it is; instead they “completely change the forest, and makes it a very different place than it was for the people who were living there.”

In other places, such as Kenya, “forest conservationists actually evict people who are living in the forest from their homes and put up fences to protect the forest,” Lavelle says. “That is not a solution that really keeps social justice and human rights in mind.”

Probably the single most important goal of the international climate negotiations is to reduce emissions. Many nations are moving toward hydropower dams as a way to make electricity without emitting excess carbon dioxide. But there's disagreement over this, too: Many of these projects do not take into account what happens to the poor people who get displaced when a dam gets put in.

"How are we carrying out these clean energy projects," Lavelle asks. "Are we making sure that the people get just compensation for land that they're giving up for these projects? Are the [local people] part of the decision-making? Is there a process that will really keep the rights of the people living on this land in account?"

There are controversial hydroelectric projects in Panama, China and countries in South America where native residents are being displaced, and now some of these projects are stalled because of protests. This is happening around the world, Lavelle says.

The new emphasis on human rights may stem in part from UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon’s appointment of Mary Robinson as his special envoy for climate change. Robinson, formerly the president of Ireland, was also the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights from 1997 to 2002.

“[Robinson] has actually taken it upon herself to make climate justice a real issue that people are talking about around the world. She has her own foundation that's dedicated to climate justice and she's going to be bringing all of these issues front and center,” Lavelle says.

Right now, the draft climate treaty does have some language about respecting human rights, but Robinson and other advocates feel it does not go far enough, Lavelle says. They believe human rights issue should be integrated into all actions on climate change.

Unfortunately, Lavelle adds, the human rights issue has the potential to slow the already painfully-slow negotiations even further — in fact, there’s no question that it already has. “Really, what’s held up these negotiations for so many years is the rift between rich and poor nations, and who is willing to put in their fair share and what is a fair share, and that really has stymied the negotiations all along.”

The social justice and human rights issues are there whether we make them explicit or not, Lavelle says. “What Mary Robinson and others are saying is, let's just put it right out there on the table and let's be clear that this is what we're talking about.”

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood