‘You send your children away because, like human beings everywhere, you want them to have a decent life’

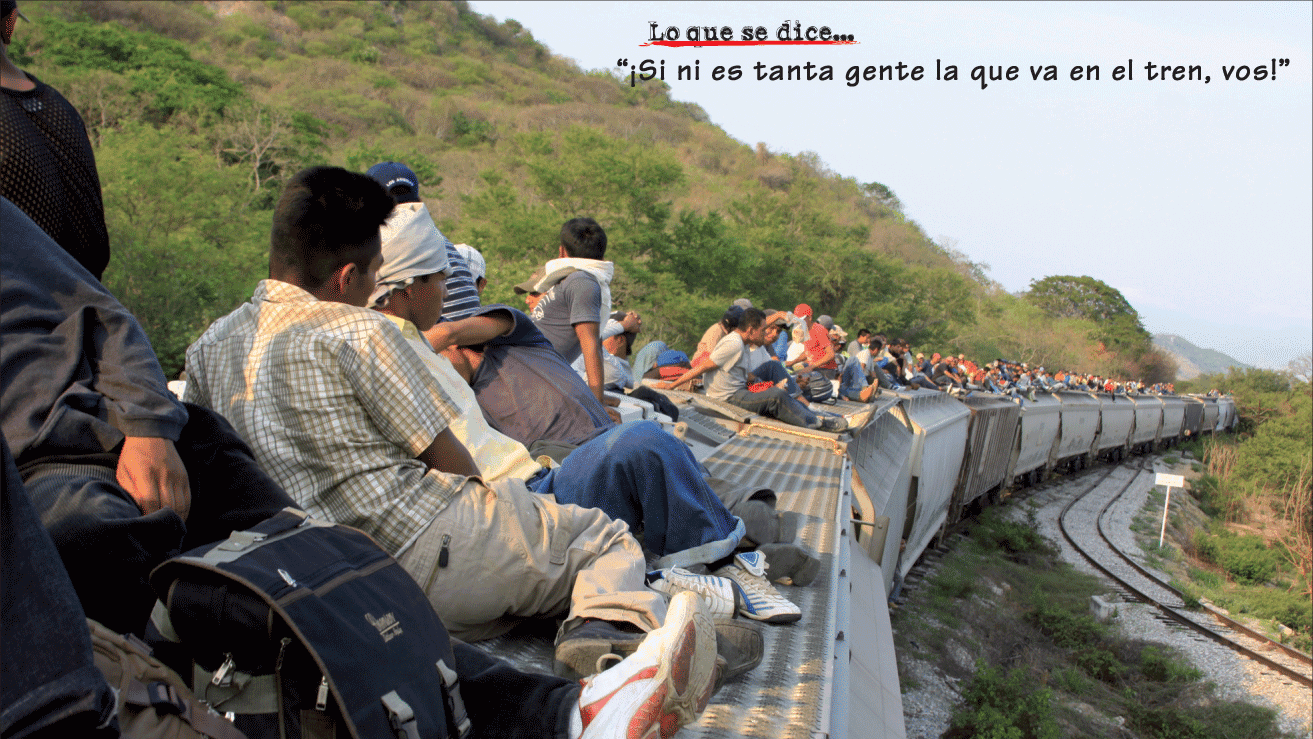

One of several ads from the government of El Salvador. This advertisement states, “They say there are not that many people on the train with you.” The country is working with the United Nation’s Population Fund to create a campaign that will encourage Salvadorians, especially youths, to be conscious of the dangers of migrating to the US.

More than 50,000 kids have been detained by US officials at the Mexican border since the beginning of 2014. That's a huge increase over 2013. Most of the kids are from Central America, and an increasing proportion of them are traveling without a parent.

Carlos Dada, director and co-founder of an online news service El Faro in El Salvador, says there are two main reasons for this phenomenon.

Firstly, there's a pull from parents who are already working in the US and sending money back home. They want their children to join them up north.

Then there is the push: the need to get away from the violence and poverty that confronts so much of the population in El Salvador.

“You send your children away because like human beings everywhere on Earth you want your children to have a decent life,” says Dada.

“If you live in a country where only one-fifth to one-quarter of the population really can hope to have a decent job; if you combine that with the extreme violence, and the lack of the presence of the state in many communities which are controlled by gangs or drug cartels, well, then, you have an explosive cocktail,” says Dada. “There’s a lack of hope.”

Dada says there’s no misunderstanding in El Salvador. He says no one there is saying the US has eased their immigration policy. However, he adds, there is, “a perception that in the case of children, laws will be applied softer, that children will not be deported as easily.”

Dada says he personally knows people affected by the crisis. One, a single mother, sent her son away after he was threatened by local gangs. “She was afraid her kid might end up killed in the streets of San Salvador.” He was around 12 years old and he made it to America, safely.

In another case, Dada met a teenager already inside the US, about 16 years old. “He himself took the road, because the gangs were threatening him [saying] if he didn’t join the gangs, they were going to kill him. So he decided he wanted to explore a different life.”

According to a UN report on human trafficking, "65 percent of victims detected in countries in North and Central America and the Caribbean are North Americans, Central Americans or nationals of the Caribbean."

Human trafficking is still big business in Central America, and most child migrants traveling overland are moved by gangs or other types of organized crime, so they are not completely alone.

But the route to the US is still extremely dangerous. Besides accidents and illness, there are often reports of robbery, rape and murder.

The government of El Salvador is doing its best to discourage people from making the journey up north.

“It’s trying to spread the message that it’s dangerous, and that you shouldn’t send your children,” says Dada. “And they’re right, because the road through Mexico is one of the most dangerous roads on Earth for human beings.”

The government is working with international agencies, like the United Nations Population Fund, getting the message out using billboards, cartoons, books and public service announcements.

“So they are trying to spread that message,” says Dada. “But then again, necessity is always bigger.”

More than 50,000 kids have been detained by US officials at the Mexican border since the beginning of 2014. That's a huge increase over 2013. Most of the kids are from Central America, and an increasing proportion of them are traveling without a parent.

Carlos Dada, director and co-founder of an online news service El Faro in El Salvador, says there are two main reasons for this phenomenon.

Firstly, there's a pull from parents who are already working in the US and sending money back home. They want their children to join them up north.

Then there is the push: the need to get away from the violence and poverty that confronts so much of the population in El Salvador.

“You send your children away because like human beings everywhere on Earth you want your children to have a decent life,” says Dada.

“If you live in a country where only one-fifth to one-quarter of the population really can hope to have a decent job; if you combine that with the extreme violence, and the lack of the presence of the state in many communities which are controlled by gangs or drug cartels, well, then, you have an explosive cocktail,” says Dada. “There’s a lack of hope.”

Dada says there’s no misunderstanding in El Salvador. He says no one there is saying the US has eased their immigration policy. However, he adds, there is, “a perception that in the case of children, laws will be applied softer, that children will not be deported as easily.”

Dada says he personally knows people affected by the crisis. One, a single mother, sent her son away after he was threatened by local gangs. “She was afraid her kid might end up killed in the streets of San Salvador.” He was around 12 years old and he made it to America, safely.

In another case, Dada met a teenager already inside the US, about 16 years old. “He himself took the road, because the gangs were threatening him [saying] if he didn’t join the gangs, they were going to kill him. So he decided he wanted to explore a different life.”

According to a UN report on human trafficking, "65 percent of victims detected in countries in North and Central America and the Caribbean are North Americans, Central Americans or nationals of the Caribbean."

Human trafficking is still big business in Central America, and most child migrants traveling overland are moved by gangs or other types of organized crime, so they are not completely alone.

But the route to the US is still extremely dangerous. Besides accidents and illness, there are often reports of robbery, rape and murder.

The government of El Salvador is doing its best to discourage people from making the journey up north.

“It’s trying to spread the message that it’s dangerous, and that you shouldn’t send your children,” says Dada. “And they’re right, because the road through Mexico is one of the most dangerous roads on Earth for human beings.”

The government is working with international agencies, like the United Nations Population Fund, getting the message out using billboards, cartoons, books and public service announcements.

“So they are trying to spread that message,” says Dada. “But then again, necessity is always bigger.”

We’d love to hear your thoughts on The World. Please take our 5-min. survey.