I had to see poverty abroad before I could see it at home

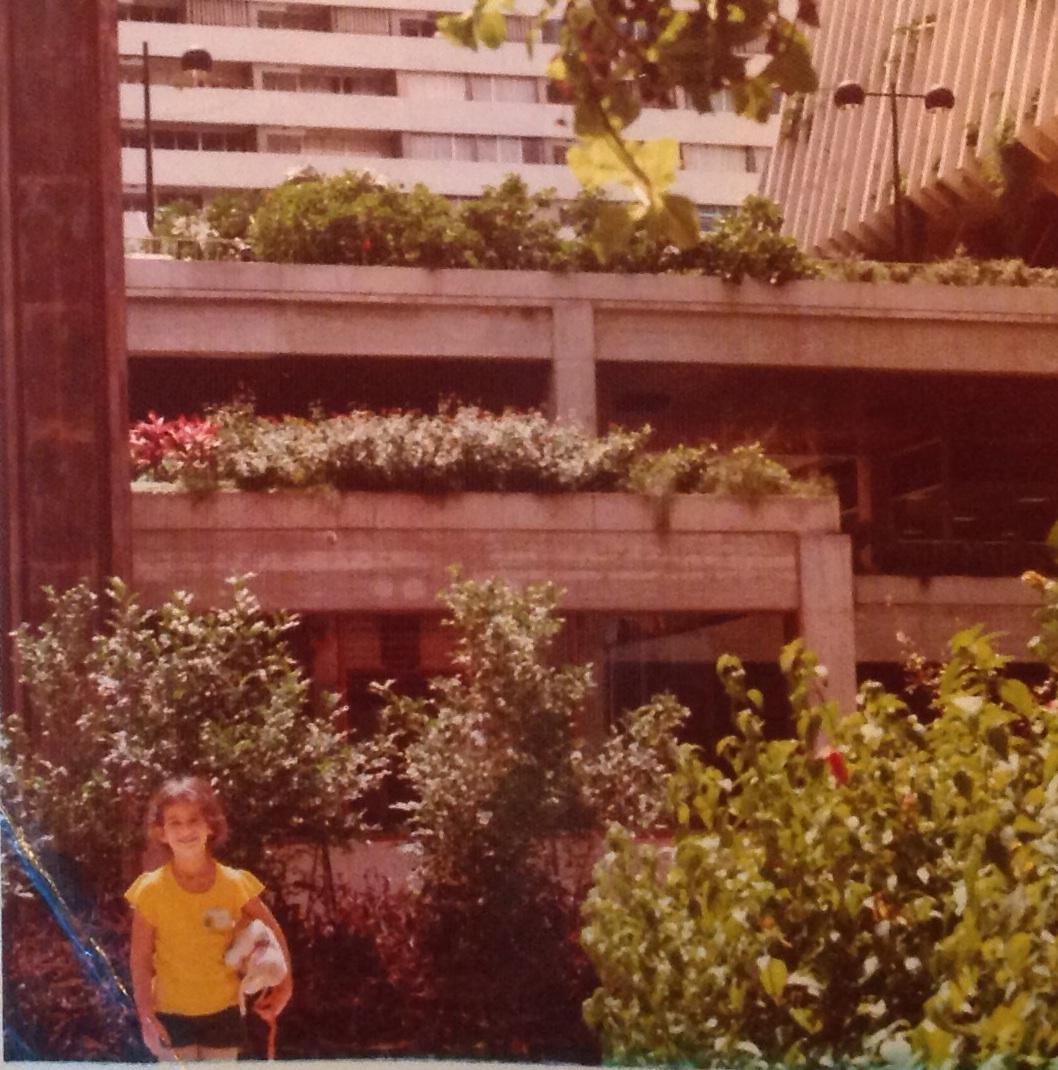

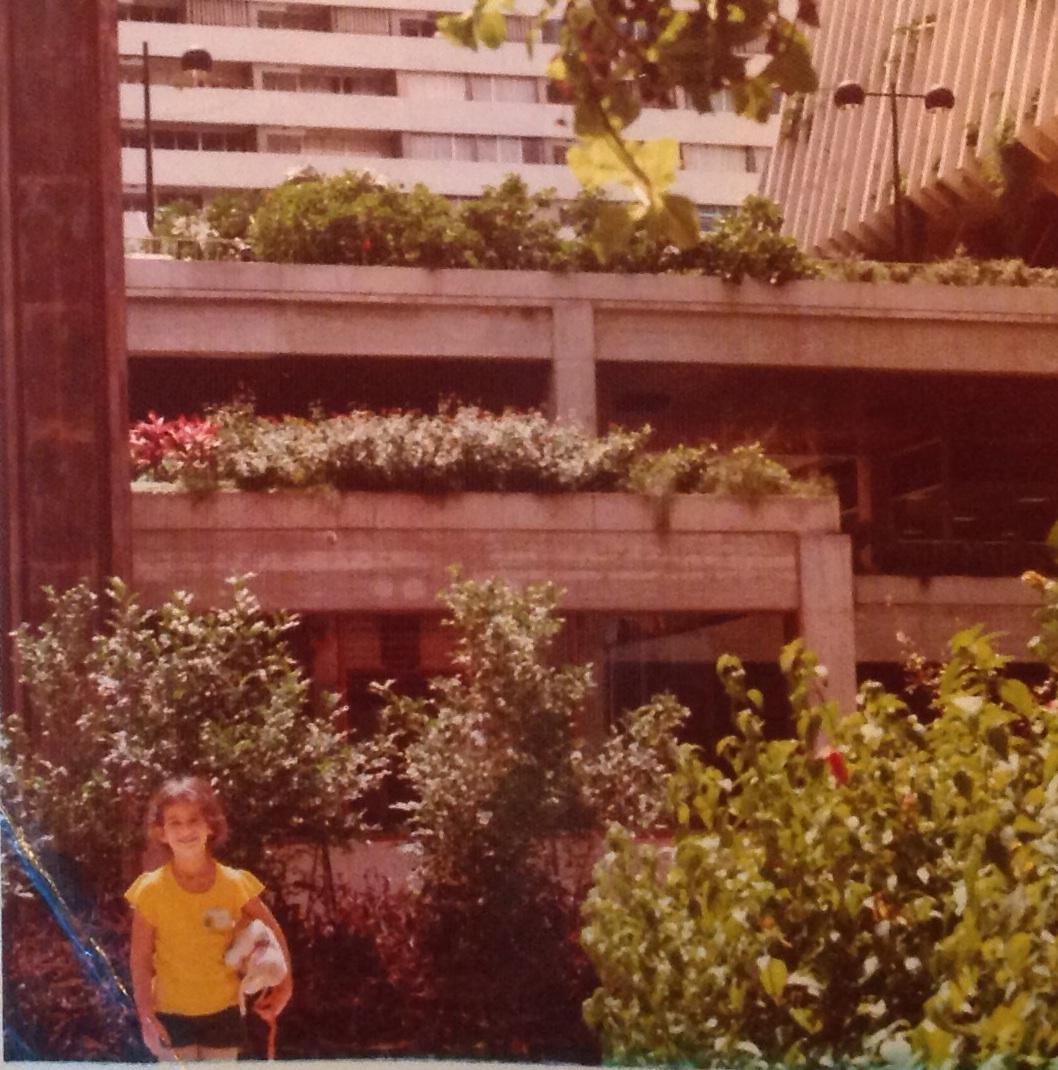

The view of a Caracas barrio in 1974 from my window.

I’ll never forget what I saw after a long night of travel. I was 6. I woke up in a posh, high-rise apartment, opened the curtains, and saw the hillside slums of Caracas, Venezuela.

Shanties and shacks made from all sorts of things — bricks, cardboard, scrap wood, and corrugated metal — one on top of the other, blanketed the hill outside. Until then, my biggest concern wasn’t poverty. It had been my stuffed bunny.

My parents tried to get me to leave it at home. They told me it might get cut open and be searched for drugs. But nothing stands in the way of a 6-year-old and her bunny. The bunny came. As did a sewing kit.

I stood at that window clutching my stuffed bunny, trying to make sense of the view. Where did those kids keep their toys? Did they even have any? What would it be like to live there?

For several weeks, I would spend the day in day care with kids of United Nations delegates, smashing pinatas, telling stupid knock-knock jokes, and learning to play the cuatro. Then I’d go back to that window and stare.

In my world back home in suburban Nashville, kids in poverty were something in TV commercials with Sally Struthers or maybe in one of the National Geographic magazines we never read. It was a problem far away.

Now it was a problem out the window, across the way, but affecting someone else.

A problem hidden in plain sight

Today, the World Bank lists the poverty rate in Venezuela at 25%. The news headlines are full of stories about the student protests against violence, poverty, corruption, and lack of opportunity.

In Michigan where I now live, one in four kids is growing up in poverty and almost 60 percent of the kids in Detroit live in poverty.

Professor Scott Allard at the University of Chicago studies poverty and says Detroit is confronted with some of the most severe poverty in our country. “When you think about abandoned buildings, open lots, the depth of poverty and the prevalence of food insecurity, it is comparable to many developing countries.”

According to UNICEF, the US is one of the worst places for childhood poverty in the developed world, and the numbers are getting worse. But Allard says this data flies in the face of how we think about ourselves.

“We don’t think about the US as a place where one in four children is poor and where children may not get enough to eat or go to a good school. It is not consistent with the self-image we have of our country and our communities.”

He says we live in communities that are segregated by class, race, and ethnicity, “so for many people it is possible to go through their entire day without actually being forced to confront the fact that there are people in their communities who aren’t getting enough to eat or don’t have a consistent place to live.”

Teddy bears get left behind

Riet Schumack sees the poverty in our country every day. She’s a community organizer in her neighborhood in Detroit.

The rental properties in Brightmoor where she lives are, as she says, “the bottom of the barrel.” They are poorly maintained and the slumlords don’t require renters to pay a security deposit. So the families who move in tend to be living on the edge.

"We don't think about the US as a place where one in four children is poor and where children may not get enough to eat."

“At a certain point, the family gets in trouble and the rent doesn’t get paid. They get evicted. Since they don’t have a car — only one in three families in this neighborhood owns a car and they can’t afford a U-Haul — they walk out with what they can carry. The rest of the contents gets dumped out in Brightmoor.”

She says nearly a quarter of the kids she works with move about three times a year and it’s been like this for the four to five years she’s known them.

"Not only do children move a lot. I, to my shock, discovered after working with kids for a couple years, that a lot of them don’t even sleep on beds or own toys," Schumack says. "You know how a child has their favorite teddy bear that they’ve had since they were two years old? Our children often don’t have that because that teddy bear was not something they could carry away from their last move.”

This isn’t just some Detroit thing

The statistics show that poverty is no longer just an urban problem. And as Scott Allard says, “The poverty problem isn’t a short-term blip.”

Pay in the US has stayed flat or declined and there aren’t well-paid jobs for low-skill workers. He says the poverty rates in suburbs are increasing and he worries that suburban residents "aren’t interested enough to figure out how to act in their own communities. There’s still a fair amount of denial.”

Both researchers like Allard and community boosters like Schumack think the solution is the same: good-paying jobs for low-skilled workers. Schumack estimates that in her community, 60 percent of the kids don’t graduate, 40 percent of the males are in jail and only one in three families owns a car. So she says, “We need an economy that can employ them locally. Once security returns to a household, then we can start working on restoration of a family and a neighborhood so we can get out of survival mode and pay attention to other aspects of life.”

Schumack says when there is no security in a child’s life, it changes their whole outlook. She says she sees how it reduces their sense of self-worth and she wonders how the kids she knows can possibly focus on their schoolwork and future plans when they don’t know whether they’ll even return to the same home after school.

I never had that worry

I still have that bunny that went with me to Caracas. It never got left behind because I never had to leave home with only what I could carry.

After two years running a journalism project about childhood poverty for Michigan Radio and hearing from researchers, service providers and people trying to create a better future for Michigan’s children, that bunny is no longer just a piece of childhood nostalgia. It is a symbol of the privilege and advantages that I was lucky enough to be born into.

I highly doubt my life would look like it does had I been born in the Caracas barrios or in Riet Schumack’s adopted neighborhood or in one of the low-rent suburban apartment buildings that are the newest home to America’s poor.

This article first appeared as part of Michigan Radio's State of Opportunity coverage, examining what it takes for children in Michigan to get ahead.

I’ll never forget what I saw after a long night of travel. I was 6. I woke up in a posh, high-rise apartment, opened the curtains, and saw the hillside slums of Caracas, Venezuela.

Shanties and shacks made from all sorts of things — bricks, cardboard, scrap wood, and corrugated metal — one on top of the other, blanketed the hill outside. Until then, my biggest concern wasn’t poverty. It had been my stuffed bunny.

My parents tried to get me to leave it at home. They told me it might get cut open and be searched for drugs. But nothing stands in the way of a 6-year-old and her bunny. The bunny came. As did a sewing kit.

I stood at that window clutching my stuffed bunny, trying to make sense of the view. Where did those kids keep their toys? Did they even have any? What would it be like to live there?

For several weeks, I would spend the day in day care with kids of United Nations delegates, smashing pinatas, telling stupid knock-knock jokes, and learning to play the cuatro. Then I’d go back to that window and stare.

In my world back home in suburban Nashville, kids in poverty were something in TV commercials with Sally Struthers or maybe in one of the National Geographic magazines we never read. It was a problem far away.

Now it was a problem out the window, across the way, but affecting someone else.

A problem hidden in plain sight

Today, the World Bank lists the poverty rate in Venezuela at 25%. The news headlines are full of stories about the student protests against violence, poverty, corruption, and lack of opportunity.

In Michigan where I now live, one in four kids is growing up in poverty and almost 60 percent of the kids in Detroit live in poverty.

Professor Scott Allard at the University of Chicago studies poverty and says Detroit is confronted with some of the most severe poverty in our country. “When you think about abandoned buildings, open lots, the depth of poverty and the prevalence of food insecurity, it is comparable to many developing countries.”

According to UNICEF, the US is one of the worst places for childhood poverty in the developed world, and the numbers are getting worse. But Allard says this data flies in the face of how we think about ourselves.

“We don’t think about the US as a place where one in four children is poor and where children may not get enough to eat or go to a good school. It is not consistent with the self-image we have of our country and our communities.”

He says we live in communities that are segregated by class, race, and ethnicity, “so for many people it is possible to go through their entire day without actually being forced to confront the fact that there are people in their communities who aren’t getting enough to eat or don’t have a consistent place to live.”

Teddy bears get left behind

Riet Schumack sees the poverty in our country every day. She’s a community organizer in her neighborhood in Detroit.

The rental properties in Brightmoor where she lives are, as she says, “the bottom of the barrel.” They are poorly maintained and the slumlords don’t require renters to pay a security deposit. So the families who move in tend to be living on the edge.

"We don't think about the US as a place where one in four children is poor and where children may not get enough to eat."

“At a certain point, the family gets in trouble and the rent doesn’t get paid. They get evicted. Since they don’t have a car — only one in three families in this neighborhood owns a car and they can’t afford a U-Haul — they walk out with what they can carry. The rest of the contents gets dumped out in Brightmoor.”

She says nearly a quarter of the kids she works with move about three times a year and it’s been like this for the four to five years she’s known them.

"Not only do children move a lot. I, to my shock, discovered after working with kids for a couple years, that a lot of them don’t even sleep on beds or own toys," Schumack says. "You know how a child has their favorite teddy bear that they’ve had since they were two years old? Our children often don’t have that because that teddy bear was not something they could carry away from their last move.”

This isn’t just some Detroit thing

The statistics show that poverty is no longer just an urban problem. And as Scott Allard says, “The poverty problem isn’t a short-term blip.”

Pay in the US has stayed flat or declined and there aren’t well-paid jobs for low-skill workers. He says the poverty rates in suburbs are increasing and he worries that suburban residents "aren’t interested enough to figure out how to act in their own communities. There’s still a fair amount of denial.”

Both researchers like Allard and community boosters like Schumack think the solution is the same: good-paying jobs for low-skilled workers. Schumack estimates that in her community, 60 percent of the kids don’t graduate, 40 percent of the males are in jail and only one in three families owns a car. So she says, “We need an economy that can employ them locally. Once security returns to a household, then we can start working on restoration of a family and a neighborhood so we can get out of survival mode and pay attention to other aspects of life.”

Schumack says when there is no security in a child’s life, it changes their whole outlook. She says she sees how it reduces their sense of self-worth and she wonders how the kids she knows can possibly focus on their schoolwork and future plans when they don’t know whether they’ll even return to the same home after school.

I never had that worry

I still have that bunny that went with me to Caracas. It never got left behind because I never had to leave home with only what I could carry.

After two years running a journalism project about childhood poverty for Michigan Radio and hearing from researchers, service providers and people trying to create a better future for Michigan’s children, that bunny is no longer just a piece of childhood nostalgia. It is a symbol of the privilege and advantages that I was lucky enough to be born into.

I highly doubt my life would look like it does had I been born in the Caracas barrios or in Riet Schumack’s adopted neighborhood or in one of the low-rent suburban apartment buildings that are the newest home to America’s poor.

This article first appeared as part of Michigan Radio's State of Opportunity coverage, examining what it takes for children in Michigan to get ahead.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!