What’s the legacy of Cesar Chavez?

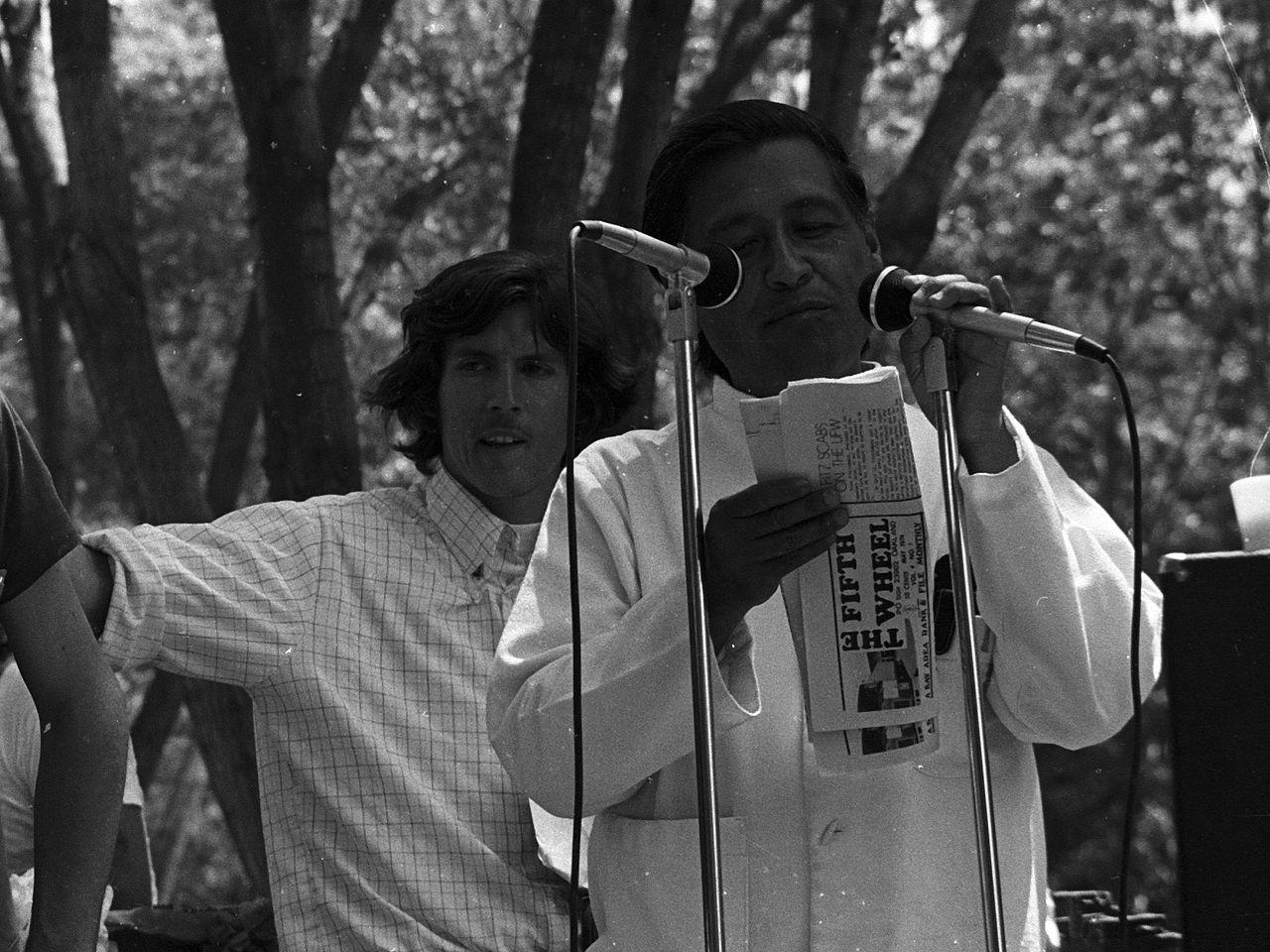

Cesar Chavez in June, 1974.

There is a story that all new members of the Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC) hear when they join: Cesar Chavez goes to a worker’s home and tells her about the farmworkers’ union and that members sustain it with their dues. She tells Chavez she is very poor and that her money is meant to provide food for her baby.

“The natural inclination for most people is to say, ‘Okay, don’t worry about it,'” says Jose Oliva, the networks director of ROC — an organization that includes some 13,000 restaurant workers. “Cesar Chavez instead said, ‘This is your organization. If you don’t give me the money, the organization won’t exist.”

Oliva considers ROC part of the Chavez legacy. Worker centers, non-profit community organizations that represent workers’ interests through mediation, advocacy, education and personal development, however, operate without the legal benefits, constraints and regulatory oversight that affect unions. Because of these differences, the centers are not without controversy. But Oliva says groups like his are designed to help union-less workers organize for themselves.

Many things have changed since Chavez’s death in 1993. Union membership in the private sector has declined greatly. In 1983, nearly 17 percent of workers were in unions. As of last year, that rate had fallen below 7 percent. Meanwhile, non-union, labor advocacy groups have risen to help improve working conditions in the new global economy.

Oliva, who is also associate director of the Food Chain Workers Alliance, will join other labor advocacy groups across the United States on Cesar Chavez Day, officially celebrated in California, Colorado and Texas on March 31, to campaign for an increase to the minimum wage.

He spoke with Global Nation about his work and the Cesar Chavez legacy.

How were you introduced to Cesar Chavez’s work?

Back in the early 1990s, a friend worked for the United Farm Workers. He told me that strawberries and some of the other products grown in the land were being touched by workers. I think it’s one of those things that people know, but we don’t think about very much. That people actually put their hands on your food, which nourishes you and goes into your body, was a revolutionary idea in my mind. It sowed the seeds, no pun intended, for a lot of what I was doing in my other work. It gave me the sudden realization that no matter how many services we provided in the community, the conditions that led to folks needing those services were still there. We needed to change the conditions of poverty in which our community lived.

The story you tell new ROC members about Chavez asking for dues is striking. Has that model of paying for representation endured?

That’s the puzzle we need to solve in the workers center movement. We’re not unions — there’s a different legal infrastructure. A union can collect dues from their members’ paychecks, but a workers center can’t do that. You don’t have a steady flow of income, which means most of our money comes from private foundations that can be cancelled at any moment. It is a completely precarious existence for worker centers.

What are the differences between worker centers and unions?

There’s a huge growth of worker centers, and a sharp decline of unions since Chavez. It’s caused by the same phenomena: the global economy, the growth of the informal sector, immigrants, people of color and women in the workforce, the decline of manufacturing. My theory is that workers centers are just third-wave unions. We had craft unions, then industrial unions in the Industrial Revolution, and now we have a new economy. That new economy has given rise to a new form of unionism that we right now call worker centers.

Worker centers don’t have the legal right to collect dues from paychecks, but doesn’t that mean they also aren’t constrained by labor laws?

The reason worker centers emerged is because unions were unable to organize workers in some of the growing sectors of the economy. The advantages to workers centers include not being constrained by the National Labor Relations Act, which has become something that is beneficial to employers. It doesn’t advantage workers at all. A report by the US Chamber of Commerce charges that worker centers are unions in disguise. I don’t believe that, but I do understand why workers would choose to organize themselves differently. Worker centers are not business unions. They’re not contract negotiation entities.

What else has changed about the workers movement since Chavez?

Chavez was ahead of his time, but he’s not ahead of our time. He was ahead of our time in terms of how far he was willing to go and how deep he was willing to push his members and his allies. But if you compare the most progressive stances he took to what progressive organizations are suggesting today, it still falls short. For instance, Chavez and his allies had no stance on LGBT issues because they felt that it was culturally inappropriate. On immigration, he definitely had mixed statements. Those are all original Chavez statements that we don’t follow or agree with.

What are the biggest successes and failures for workers since Chavez?

Chavez gave birth to an era of what I would call ‘labor self-awareness.’ Unions and other worker organizations began to pay attention not just to their growth, but to who was leading them and what influence they could have on politics. Before that, they were naval-gazing. Chavez pushed the labor movement in a whole new direction. On the negative side, it’s all metrics. I definitely see the labor movement as a shadow of what it once was, especially while Chavez was around. In the heyday of the labor movement, unions represented about one-third of the workforce. Today, less than 9 percent of private sector workers belong to a union. That is evidenced in the collapse of wages and conditions around the private sector. The legacy of Chavez is something that has allowed us to grow as a movement, if not in numbers, at least morally. Hopefully that moral re-centering is going to provide us with the vision that we need to grow physically.

Does Cesar Chavez matter a lot for Latinos?

There is no other leader that the mainstream of society has chosen to highlight in the Latino community, even though there are many people who have being doing amazing work in different realms of society. Of course, we’ll take him, because he’s all we have. On the other hand, he’s not a Latino civil rights leader. He fought for labor issues and farmworkers. I don’t know if the mainstream media knows what to do with that. All the heroes that we’ve chosen to highlight are people like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X who have done amazing things for ‘their people.’ They fought in the realm of human rights, not labor rights. In that respect, it’s really hard, especially for the media, to figure out what to make of Cesar Chavez.

Why use Cesar Chavez Day to fight for the Fair Minimum Wage Act?

Food workers now make up one-fourth of all food insecure people in the US. Ironically, the people who are responsible for putting food on your table are often unable to put food on their own table. Cesar Chavez was right. We need to come together, not just as food workers, but as a society to eliminate the root causes of that hunger and poverty. Raising the minimum wage is a step in that direction. It can improve the lives of somewhere between 10 and 15 million families in the US.

There is a story that all new members of the Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC) hear when they join: Cesar Chavez goes to a worker’s home and tells her about the farmworkers’ union and that members sustain it with their dues. She tells Chavez she is very poor and that her money is meant to provide food for her baby.

“The natural inclination for most people is to say, ‘Okay, don’t worry about it,'” says Jose Oliva, the networks director of ROC — an organization that includes some 13,000 restaurant workers. “Cesar Chavez instead said, ‘This is your organization. If you don’t give me the money, the organization won’t exist.”

Oliva considers ROC part of the Chavez legacy. Worker centers, non-profit community organizations that represent workers’ interests through mediation, advocacy, education and personal development, however, operate without the legal benefits, constraints and regulatory oversight that affect unions. Because of these differences, the centers are not without controversy. But Oliva says groups like his are designed to help union-less workers organize for themselves.

Many things have changed since Chavez’s death in 1993. Union membership in the private sector has declined greatly. In 1983, nearly 17 percent of workers were in unions. As of last year, that rate had fallen below 7 percent. Meanwhile, non-union, labor advocacy groups have risen to help improve working conditions in the new global economy.

Oliva, who is also associate director of the Food Chain Workers Alliance, will join other labor advocacy groups across the United States on Cesar Chavez Day, officially celebrated in California, Colorado and Texas on March 31, to campaign for an increase to the minimum wage.

He spoke with Global Nation about his work and the Cesar Chavez legacy.

How were you introduced to Cesar Chavez’s work?

Back in the early 1990s, a friend worked for the United Farm Workers. He told me that strawberries and some of the other products grown in the land were being touched by workers. I think it’s one of those things that people know, but we don’t think about very much. That people actually put their hands on your food, which nourishes you and goes into your body, was a revolutionary idea in my mind. It sowed the seeds, no pun intended, for a lot of what I was doing in my other work. It gave me the sudden realization that no matter how many services we provided in the community, the conditions that led to folks needing those services were still there. We needed to change the conditions of poverty in which our community lived.

The story you tell new ROC members about Chavez asking for dues is striking. Has that model of paying for representation endured?

That’s the puzzle we need to solve in the workers center movement. We’re not unions — there’s a different legal infrastructure. A union can collect dues from their members’ paychecks, but a workers center can’t do that. You don’t have a steady flow of income, which means most of our money comes from private foundations that can be cancelled at any moment. It is a completely precarious existence for worker centers.

What are the differences between worker centers and unions?

There’s a huge growth of worker centers, and a sharp decline of unions since Chavez. It’s caused by the same phenomena: the global economy, the growth of the informal sector, immigrants, people of color and women in the workforce, the decline of manufacturing. My theory is that workers centers are just third-wave unions. We had craft unions, then industrial unions in the Industrial Revolution, and now we have a new economy. That new economy has given rise to a new form of unionism that we right now call worker centers.

Worker centers don’t have the legal right to collect dues from paychecks, but doesn’t that mean they also aren’t constrained by labor laws?

The reason worker centers emerged is because unions were unable to organize workers in some of the growing sectors of the economy. The advantages to workers centers include not being constrained by the National Labor Relations Act, which has become something that is beneficial to employers. It doesn’t advantage workers at all. A report by the US Chamber of Commerce charges that worker centers are unions in disguise. I don’t believe that, but I do understand why workers would choose to organize themselves differently. Worker centers are not business unions. They’re not contract negotiation entities.

What else has changed about the workers movement since Chavez?

Chavez was ahead of his time, but he’s not ahead of our time. He was ahead of our time in terms of how far he was willing to go and how deep he was willing to push his members and his allies. But if you compare the most progressive stances he took to what progressive organizations are suggesting today, it still falls short. For instance, Chavez and his allies had no stance on LGBT issues because they felt that it was culturally inappropriate. On immigration, he definitely had mixed statements. Those are all original Chavez statements that we don’t follow or agree with.

What are the biggest successes and failures for workers since Chavez?

Chavez gave birth to an era of what I would call ‘labor self-awareness.’ Unions and other worker organizations began to pay attention not just to their growth, but to who was leading them and what influence they could have on politics. Before that, they were naval-gazing. Chavez pushed the labor movement in a whole new direction. On the negative side, it’s all metrics. I definitely see the labor movement as a shadow of what it once was, especially while Chavez was around. In the heyday of the labor movement, unions represented about one-third of the workforce. Today, less than 9 percent of private sector workers belong to a union. That is evidenced in the collapse of wages and conditions around the private sector. The legacy of Chavez is something that has allowed us to grow as a movement, if not in numbers, at least morally. Hopefully that moral re-centering is going to provide us with the vision that we need to grow physically.

Does Cesar Chavez matter a lot for Latinos?

There is no other leader that the mainstream of society has chosen to highlight in the Latino community, even though there are many people who have being doing amazing work in different realms of society. Of course, we’ll take him, because he’s all we have. On the other hand, he’s not a Latino civil rights leader. He fought for labor issues and farmworkers. I don’t know if the mainstream media knows what to do with that. All the heroes that we’ve chosen to highlight are people like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X who have done amazing things for ‘their people.’ They fought in the realm of human rights, not labor rights. In that respect, it’s really hard, especially for the media, to figure out what to make of Cesar Chavez.

Why use Cesar Chavez Day to fight for the Fair Minimum Wage Act?

Food workers now make up one-fourth of all food insecure people in the US. Ironically, the people who are responsible for putting food on your table are often unable to put food on their own table. Cesar Chavez was right. We need to come together, not just as food workers, but as a society to eliminate the root causes of that hunger and poverty. Raising the minimum wage is a step in that direction. It can improve the lives of somewhere between 10 and 15 million families in the US.