Snowden revelations lead Russia to push for more spying on its own people

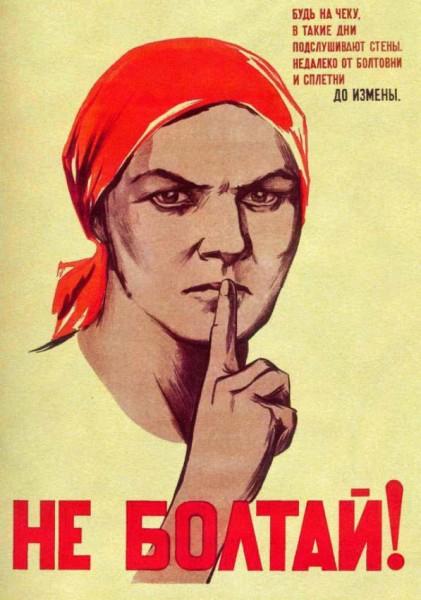

“Don’t Blab” warns people to keep their secrets to themselves in this Soviet-era poster.

Russians didn't invent spying, but Americans of a certain age could be forgiven for thinking Russians were the innovators.

At the height of the Cold War, the US government warned of Soviet spies blending into small town America, listening in on conversations with an array of cutting-edge spyware, like tiny microphones embedded in walls or under floors.

These days, there are many other ways of eavesdropping, and it's the US that's seen as the innovator — based on the avalanche of leaks from former NSA contractor Edward Snowden.

Russian state media have had a field day covering the revelations from Snowden, who’s living in Moscow under temporary asylum. But left unsaid is that Russia's secret services conduct similar monitoring through their own program, called SORM. It gives intelligence agencies remote access to all of Russia's telephones, text messages, emails, chats and Internet searches.

“It's much different than the western approach,” says Andrei Soldatov, an investigative journalist with Agentura.ru, an online publication that monitors Russia's intelligence services. “[SORM] is much more intrusive and totalitarian in its nature.”

According to Soldatov, SORM was traditionally limited to domestic communication, but the Snowden revelations are changing that. Now, Russia's FSB, the domestic successor to the Soviet KGB, is seeking backdoor access to Yahoo, Gmail, and other western Internet services as a prerequisite for doing business in Russia.

“The FSB was always very keen to get access to western-based email accounts and email services because they believe they should be completely transparent for the Russian authorities,” Soldatov says. “Now, Snowden's revelations have made an excellent excuse for the Russian authorities to pressure global services to have their servers hosted on Russian soil.”

Such a move, government officials argue, would help Russia fight domestic terrorist threats. But critics point to Russia's pattern of abuse aimed at political enemies at home.

Tanya Lokshina, deputy director for Human Rights Watch in Moscow, knows this better than most. She’s been harassed and threatened by what she believes are Russian security services, because of her work.

“In Russia's human rights community, pretty much everyone believes that he's been under surveillance. When they talk on their cell phones, people are conscious that they are probably being listened to by the special services,” Lokshina says, “that their email conversations are likely being intercepted. No one feels safe. This is just part of their daily lives; Big Brother is watching.”

Russia's political opposition figures, like the anti-corruption crusader Alexey Navalny, are also regular targets. The government has launched a slew of criminal prosecutions against him — many call it retaliation for his work exposing government malfeasance.

And what was among the evidence prosecutors presented in court? Recordings of Navalny's private phone conversations from several years earlier.

The legality of that is questionable, but there's little public debate in Russia over government intrusion. According to Andrei Soldatov, it's in part a legacy of Soviet times, when spying was the norm.

It's also because when it comes to the privacy vs. security debate, there just isn't one in Russia.

“The question about security is much more important than privacy,” Soldatov says. “The usual answer is, 'well I have nothing to hide and I'm very concerned about my security or the security of my children and that's a price I'm willing to pay.'”

But that security-above-all argument can cut both ways.

Russians are increasingly turning to surveillance technology to watch the state. For example, dashcams — those onboard video cameras that have turned Russian drivers into a YouTube sensation — are regularly used to fend off corrupt police in search of bribes. It’s a reminder that in Russia, the best defense when it comes to surveillance may be to surveil yourself.