The Manchus ruled China into the 20th century, but their language is nearly extinct

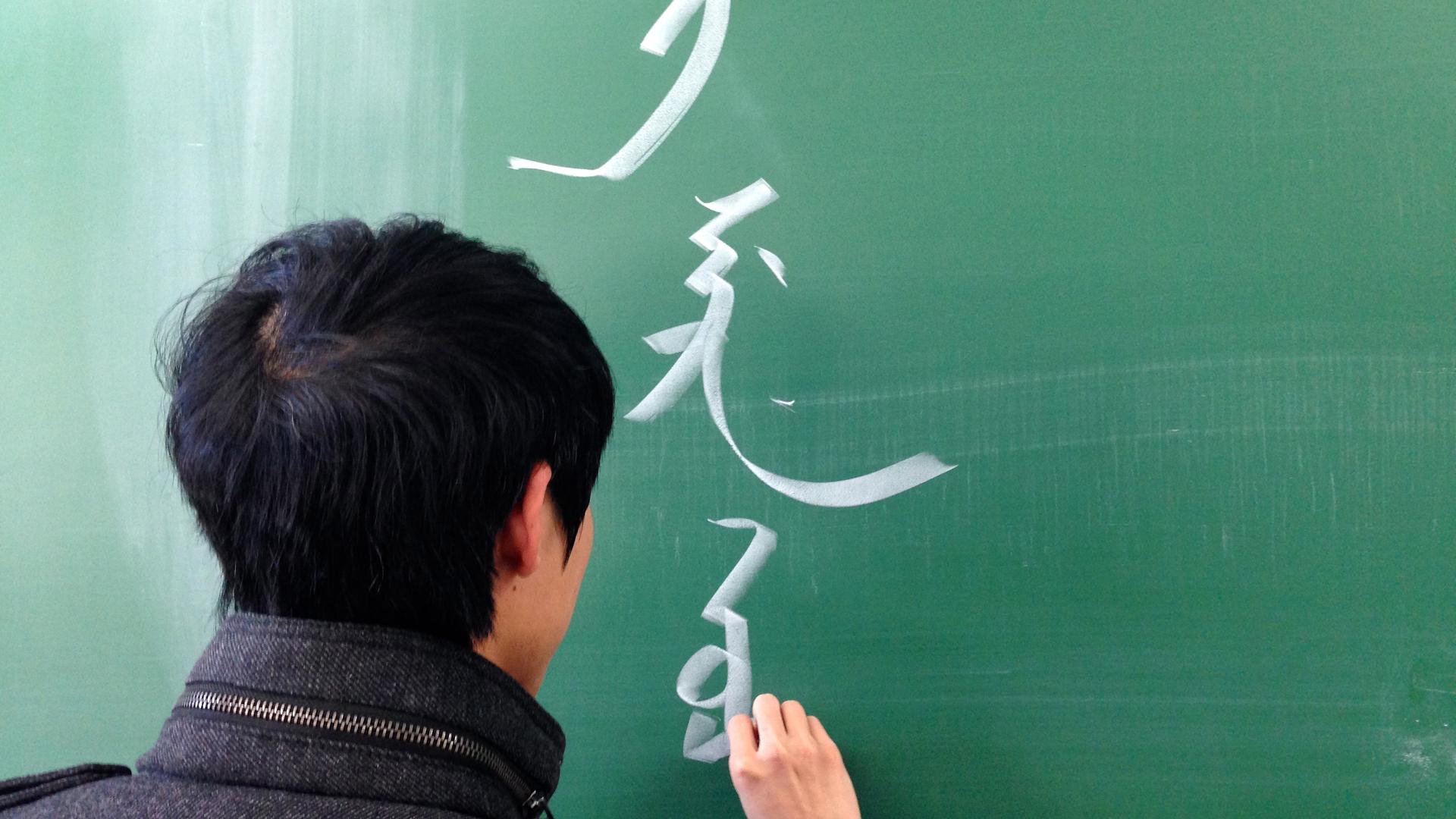

Manchu language class at People’s University in Beijing.

Wei Hubu was quick to make reference to my height. I met the 30-year-old language instructor after class at People's University in Beijing.

"We Manchus used to be tall just like you," he pointed out as we walked to the university cafeteria. At 6'4", I'm at least a foot taller than Wei.

"But most Manchu men were warriors, and they all got wiped out," he said with an ironic chuckle.

In 2013, China's ethnic Manchu minority is in little danger of being wiped out. It's more than 10 million strong. But the Manchu language is another story. It's on the verge of extinction.

Well aware of this fact, Wei is among a small number of people trying to avert what they see as a looming disaster.

The end of the Qing Dynasty

The last emperors of China belonged to the Qing Dynasty, a fascinating era in Chinese history that begins in the 17th century and ends in 1911. Every Chinese school kid knows 1911 as a turning point, when thousands of years of imperial rule in China finally came to a close.

Thanks in part to popular television soap operas, people in China have something of an idea what Manchu rule looked like. Or at least how China's Manchu rulers might have dressed. What is far from authentic in these period drama series, though, is the dialogue.

Thanks in part to popular television soap operas, people in China have something of an idea what Manchu rule looked like. Or at least how China's Manchu rulers might have dressed. What is far from authentic in these period drama series, though, is the dialogue.

Actors in the soaps speak Mandarin Chinese, the national language of the People's Republic since the 1950s. But during the Qing era, government officials were actually foreigners. Officials in the Chinese court were Manchus from the northeast, mostly beyond the Great Wall, near the border with Korea. Manchuria is the English name of the region.

The Manchus had their own language, too. And naturally, Manchu became the language of all official business during the Qing Dynasty.

Like Wei Hubu, most of the students in his classroom at People's University are ethnic Manchus themselves, there to learn the language of their ancestors.

After class, Wei was kind enough to teach me a few phrases in Manchu. To my non-expert ears, Manchu sounds a lot more like Korean than Chinese.

How Manchu is written

Manchu script is very different from Chinese characters. It’s more like Mongolian. It's also phonetic, like English, with each letter of the Manchu alphabet corresponding to a specific sound.

Wei admitted that he’s as much student as teacher. He comes from a Manchu family, but only started studying the language a couple of years ago. He said Manchu won't help him professionally. He is mainly trying to get in touch with his Manchu roots, and — he hopes — to make a modest contribution to the effort to save Manchu from disappearing completely.

"If Manchu dies out," Wei told me, "so much will be lost. Language is the soul of a culture. People would never truly understand Manchu culture and history."

Under official Chinese government policy, the languages of ethnic minorities are protected. But attitudes among the Chinese public can be less than charitable. More than 90 percent of China's 1.3 billion people belong to the same ethnic group, the Han. And many of them see little reason to preserve certain cultural relics of the past.

Apathy toward Manchu

During an evening walk at the summer palace of the former Qing emperors in Beijing, I ran into a 26-year-old lawyer named Chen. The park is a popular historic spot. With some pride, Chen took a look around at the ancient monuments and said that he is captivated by the legacy of the Qing Dynasty, but not the Manchu language.

"I'm Han ethnicity, so I don't know much about the Manchu language," he said.

I asked Chen what he thought about the effort to save the language from extinction.

"My personal opinion is that we should let it be, because some languages will slowly fade away," Chen replied matter-of-factly. "I don't think we should do something to intentionally preserve them. What will die out, will finally fade away."

It’s hard to find much enthusiasm for the Manchu language among most of the Chinese public. That might have something to do with the fact that Manchu has been fading away for a long, long time.

In the 18th century, China’s Manchu rulers lifted the ban on intermarriage, allowing Manchus and Han Chinese to get married and start families. At the same time, Manchu officials were told they had to start studying Mandarin.

A link to the past, including traditional medicine

Fast forward to the present day, and no one in China speaks Manchu as a first language, according to Cao Meng, a Manchu language professor at Shenyang Normal University, north of Beijing. Cao said fewer than a hundred people can read classical Manchu fluently. But the professor disagreed with the suggestion that Manchu is already a dead language. Not yet, at least.

"The Manchu ethnicity is one of China's largest in terms of population," Cao told me. "It would be a national shame if the language was allowed to die out completely."

Cao explained that there are troves of untranslated materials written in the Manchu language. These sources are full of information about family histories, government policies, and other subjects close to the hearts of many Chinese people, like traditional medicine.

"This knowledge could be lost forever," Cao said. So, the professor — who is Han Chinese — is working to promote the study of Manchu starting in grade school.

For others though, it’s more personal.

One Manchu language instructor told me she understands the language a lot better than her parents do. She is also from a Manchu family. So, to help her folks get in touch with their cultural roots as well, she makes them listen to pop music with Manchu lyrics.