A teen who escaped Syria waits for a future in the US

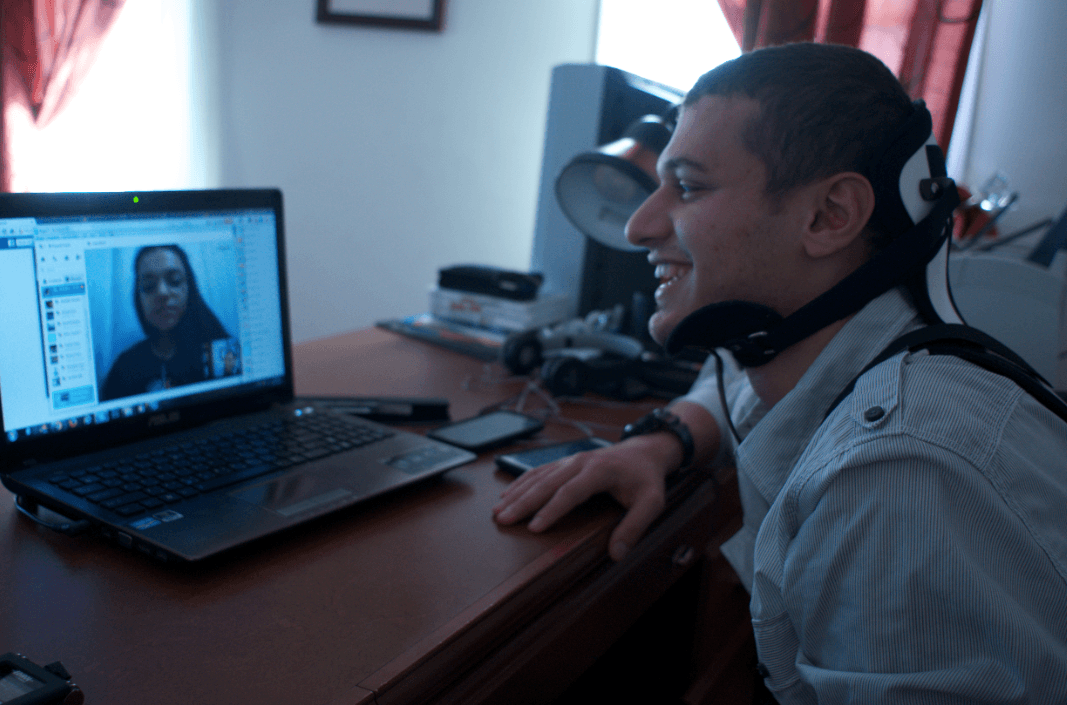

Fouad Faris, 19, sits at his computer in Shrewsbury, MA, video-chatting with his sister, Rama, who is in Turkey. Faris wears a neck brace because he is recovering from a bike accident.

Lately, Fouad Faris spends most of his time on the computer, scrolling and clicking on Facebook pages that offer news from Syria. He video-chats with friends and family who are now far-flung: some are in Syria, others are sheltered in places like Turkey and Jordan.

A year ago, the 19-year-old left behind the tear gas and explosions in Syria for the safety of a suburb in Massachusetts.

Faris had lived in Aleppo, his hometown, and Damascus, where he attended dental school, while the conflict between the Syrian government and rebels grew. There were military checkpoints, the echo of explosions, and heightened suspicions among strangers. Faris said he adjusted to the changes and carried on with a relatively normal life, going to classes and hanging out with friends.

"If you're there, you get used to it," he said. "When you get the shocks one by one, it's all gonna be the same."

Things got worse, though, last August. Faris was at home in Aleppo during a school break. He was in the garden with his sister, Rama. They heard a loud boom.

"Two bombs dropped just 20 feet next to the house. The war started in Aleppo. Real war, like the tanks started to come over, aircraft, everything," he said.

Faris' father, stepmother, and three youngest siblings were already in the United States seeking asylum. When they heard about the increasing danger in Aleppo, they urged Fouad and Rama to leave.

Now, the entire family has left Syria, but they are separated by states and continents. Rama has applied three times for a US visa, but hasn't had luck. Why is unclear. She is living with relatives in Turkey in the meantime.

Faris' parents moved to a suburb of Birmingham, AL, where living costs are low.

Faris is in Massachusetts because he thought there would be more to do there. He lives at his aunt and uncle's house, in the quiet suburb of Shrewsbury, MA.

“Sometimes I feel so lucky, and sometimes I feel not lucky at all,” Faris said.

It's been more than seven months since he filed for asylum, as a beneficiary through his father's application. He awaits word from immigration officials.

Over the past three years, the number of asylum applications received by the US from Syrian immigrants has increased sharply. In 2010, before Syria's war began, there were fewer than 50 cases, with each representing either one person or an entire family's application. This year, there are more than 1,300 cases.

While waiting, Faris is unable to enroll in local college classes or get a job because he doesn’t have a social security number.

So he spends his time in front of the computer.

On a recent weekday evening, Faris talked over the internet with his sister in Turkey. Then, he went on Facebook and checked updates from a page called Eyewitness News of Aleppo. There were posts about water and electrical outages in the city.

He then clicked over to a video his uncle filmed, showing the Aleppo street where Faris’ grandmother used to live. It showed burnt buildings along a rubble-lined street.

“Seeing cities destroyed … it’s bad for me,” Faris said. “Neigborhoods where I used to play are destroyed.”

Faris knows it would be dangerous to return to Syria, but a mix of boredom and guilt makes him want to return.

“There’s no difference between me and those people, we’re all the same,” he said. “Why they have to suffer while I’m not? We’re both Syrians, we’re both from same town, living the same neighborhood. What’s the difference? Why them, not me? We’re all equal right?”

Faris tries to transport himself back home through his computer screen. He listens to music supporting the Syrian rebellion and talks with his friends, who are scattered in Syria or living in other countries as refugees or asylees.

He hopes his asylum will be granted in time to enroll in community college classes in January.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!