Apathy? Argentina’s newly empowered teen voters say ‘no way’

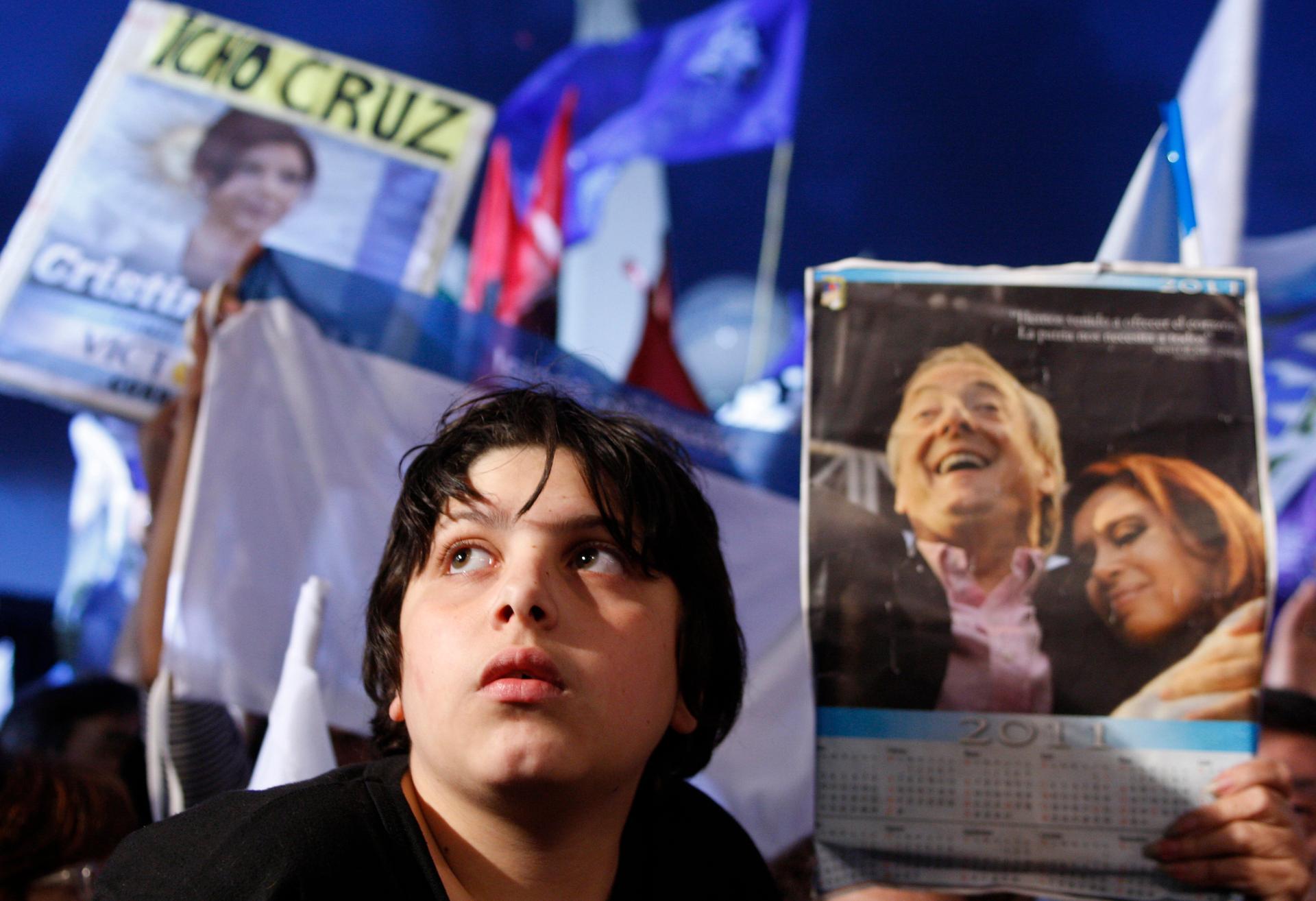

A young supporter of President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner waits at an election rally. The president hopes to harness the power of teen voters in elections later this month.

This October, Argentina’s sixteen and seventeen-year-olds will vote in their first general elections.

The legislature granted them the right to vote last September in what some called a "vote grab" by the ruling party, President Cristina Kirchner’s Front for Victory. But the country’s teens don’t see it that way, and polls project a high turnout among the country’s youngest voters in this month’s legislative elections.

In high school after high school around Buenos Aires, the city government has organized special classes about voting. By election time, 35,000 16- and 17-year-olds will have taken the classes, which teach all there is to know about the country’s electoral system.

“In general, we’re all lazy. No one wants to get up early on a Sunday morning to go vote.”

— Axel, 17, Buenos Aires

But a remarkable number of Argentina’s youth — 75 percent of those eligible — say they will get up on Sunday, Oct, 27 to vote. And it’s not even a presidential election year.

It seems a lot of teens feel they can make a difference on issues important to them.

“Everyone contributes their little grain of sand to make the huge number of votes," said 16-year-old Damián Mas. "What’s important is that we’re interested and we vote. The country depends on our votes.”

Mas says he’s planning on voting for President Kirchner’s Front for Victory Party in October, because he “likes how they’re running the country.”

“I like how education has evolved and how many more schools they’ve built," he added. "I also like that young people can vote — that is very good — and I like the universal cash payments to poor families with children."

Across town, at Buenos Aires’ National High School, 17-year-old Ricardo Arraga is also excited about going to the polls.

“I’m going to try to make the revolution. I mean, maybe you can’t change the situation, but you have to try,” Arraga said.

Like Mas, Arraga is focused on education, though he’s not as excited about the government’s record. He says a better educational system would be the solution to Argentina’s high crime rate.

Regardless of whom they plan to vote for, Arraga says his peers are expending so much energy learning and talking about the elections because “they see this right like a tool for making a change in society. Maybe [they] feel more important, like, ‘Oh, my opinion matters.’”

This sentiment is music to Mariano Heller’s ears. Heller, a law professor at the University of Buenos Aires, is one of the many instructors of the high school voting class. He says the class doesn’t push any particular candidates, political parties or issues: The goal is just to get kids involved.

“We teach some concepts related to democracy, republics, the division of powers,” he says. “Then we talk about topics specifically related to voting – different kinds of votes, valid votes, invalid votes, how blank votes work.”

Some Argentines aren’t terribly happy about granting 16-year-olds the right to vote. Indeed, polls indicate the new voters lean left, a boon for President Kirchner's party.

But while young people might make a difference, their votes likely won’t swing the election: They represent only about two percent of the country’s eligible voters.

Yet, it seems, they still plan to show up in droves.