Here’s how a controversial work of art healed America after Vietnam

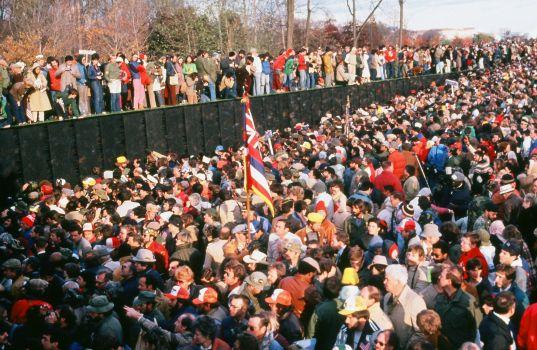

The crowd at the 1982 dedication of the memorial.

How do you build a monument to a war that was more tragic than triumphant? Maya Lin was practically a kid when her design was selected to become the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, DC. And her design was nearly as controversial as the war it commemorated.

“The veterans were asking me, ‘What do you think people are going to do when they first come here?’” Lin recalls. “And I wanted to say, ‘They’re going to cry.’"

Her minimalistic granite wall was initially derided as a “black gash of shame” by Vietnam veteran Tom Carhart. Carhart pushed for a more traditional monument and even submitted an entry into the contest featuring him carrying a fallen comrade. Some saw it as an anti-war statement; others wondered why an Asian-American should be the designer.

However, the initial hostility has faded, and the monument has since become a near-universally treasured piece of public sculpture.

Inscribed with the name of every fallen soldier, it became a sacred place for veterans and their families. It's also influenced later designs like the World Trade Center Memorial, which also features the names of the dead etched into black stone.

"For me, the names were key to it and they were about the individuality of each person," says Michael Arad, designer of the World Trade Center Memorial. "I wanted to mark the collective loss but also the individual loss that one by one by one created this tally."

Some in the military saw the somber tone of the memorial as anti-war.

"The problems they saw were that it wasn't celebratory, that it made fighting and dying in an American war seem tragic," says historian Kristin Haas. "The idea of millions of schoolchildren year after year going to the National Mall and standing at the Vietnam Memorial and thinking 'This is what it means to be an American soldier?' produced a lot anxiety on the part of people who were trying to recruit those kids to be in an all-volunteer military."

Lin, the designer, admits the wall doesn't glorify the war, which many Americans considered unworthy of the sacrifice it required. Yet, she believes that it succeeds in glorifying the human lives lost in battle.

The monument's location, stretching between the Lincoln and Washington monuments, adds to its air of respect, says journalist Laura Palmer, who was a reporter in Saigon in the early 1970s. "These men and women who were reviled and stigmatized are joined with the two greatest presidents in our history," she says.

"The important thing to know about the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is that it made memorials matter again," says historian Haas.

"The practice that is ubiquitous now of, at the site of some kind of public tragedy, people bringing their teddy bears and their toys and letters and flowers… it didn't happen in public places in the United States before Maya Lin's memorial."

And every item that is left behind at the Wall is saved at the National Parks' Museum Resource Center in Maryland.

Studio 360 host Kurt Andersen explores the stories of those objects and of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in a powerful audio portrait that is part of the American Icons series from Studio 360. Below, a slideshow from the memorial.