In Sudan, women moving to shed pounds as ideal body image changes

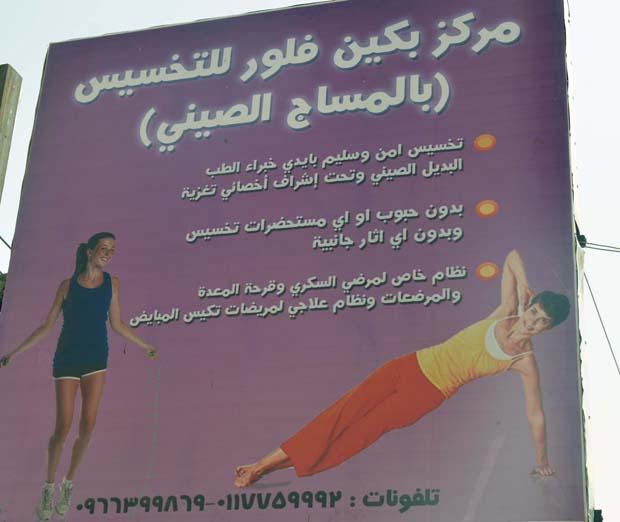

This billboard in Khartoum is encouraging women to lose weight. (Photo by Hana Baba.)

About 20 women are taking an aerobics class at the Sama Style health club in the upscale Khartoum neighborhood of Riyadh.

It’s a weekday morning so these are mostly Khartoum housewives. Many are clearly overweight, and a few verge on obese.

This is a women’s-only gym — there’s not a male in sight, which is important in a conservative country like Sudan.

In addition to the aerobics room, there’s a pool, a gym room with treadmills, elliptical machines and other equipment, as well as a salon where women can get their hair done, get henna designs on their hands and feet, or get scrubbed down in a Moroccan hammam bath after a workout. Amal Ahmed, a trainer at the club, says demand is high, and classes are full.

“Most women that come say they don’t want to be fat so they don’t get diseases,” she said. “They are afraid of arthritis and back pain. They all want to be slim.”

Not so long ago, Sudanese women were encouraged to be plump. The larger the girth, the more desirable a woman was for marriage. But that is slowly changing. Rising diabetes rates combined with the spread of a more global image of the “ideal woman” are convincing a new generation of middle-class, urban women that thinner is better.

Ahmed says women here used to avoid going to the doctor because they knew they’d be told to lose weight. But now, they are heeding that advice. At least 30 fitness centers have sprung up in Khartoum in the past few years.

Nafisa Bedri of the Ahfad University for Women and her students have been researching obesity rates in Khartoum, which are on the rise. She says some of the culprits are urbanization, a new sedentary lifestyle and the increasing availability of numerous TV channels and junk food.

But Bedri says the urge to shed pounds isn’t just about health.

“The media has created this image among young women that they have to be very thin,” she said. “They want to be skinny like the models they see in magazines and on satellite television.”

Turn on the TV and you’re bombarded with infomercials for weight loss products, with images of svelte Lebanese and Egyptian women flashing across the screen. So Sudanese women feel pressure to drop the pounds. And, according to Bedri, Sudanese society is now more tolerant of women going outdoors to exercise.

“You see more and more people walking around the street,” Bedri said. “It’s more acceptable for a woman to be exercising. Unlike a few years ago, when men would harass her, now people are accepting this. They are respecting this, actually.”

Weight loss never used to be a priority here. As little as two generations ago, the custom was to fatten up Sudanese girls before their weddings. Sadia Elsalahi, a folklore historian, says this cultural affinity for plump women was rooted in history.

The people living at the time of the ancient Kush civilization, which ended in 350 AD, favored full bodies — especially thick hips and thighs. Until the 1930s, Sudanese used to marry off their daughters as young as 11 and 12, when their bodies hadn’t fully developed.

“To make a girl seem older,” Elsalahi said, “they made her bigger and fatter.”

When a girl got engaged, she said, they would cut a large hole in the center of a bed. The small girl would sit in the hole, and then over the next year, they fed her fatty foods and starchy drinks — all while in the bed. As she grew bigger and filled up the hole, she was considered ready for the wedding.

There was also an economic incentive to fatten up the bride. Elsalahi says before the wedding, a bride would sit in a smoke bath of burning perfumed acacia wood, twice a day for 40 days. During that period, she wouldn’t wash. Her body would be basted with aromatic oils until a thick layer formed on her skin, kind of like an overdone barbecue.

On day 40, the thick sooty layer would be peeled off revealing glowing skin underneath. That layer, the “banooteya,” would be folded up and sent to the groom’s family, who’d weigh it. Whatever the weight, the groom would match in gold for the bride. So the larger the woman’s body surface area, the more gold the family would get.

That was then.

At the Afhad University for Women in Khartoum, six young women in pressed long sleeved T-shirts and smart pencil skirts take a break under a tree. They’re all management students. Tibyan Yaseen says she feels like she needs to lose weight — it’s what the guys want nowadays.

“They see superstars on TV, like Rihanna and Beyoncé, and so we want to be like that,” she said.

Yaseen’s friend, Hanaa Mubarak, says she, too, wants to lose weight — but her mom keeps sabotaging her with calorie-rich, full-fat Sudanese cooking.

“My mom says ‘Hanaa, eat more of this, drink a lot of that, you need to get fatter.’ But my skirt is tight,” she said. “I want to feel lighter like the rest of the girls.”

So what does she do to lose weight?

“I don’t do anything. I just eat more,” she said, laughing with her friends. “I really feel bad because I can’t lose weight. I want to cry.”

At Sama Style Center, trainer Amal Ahmed says they’re attracting more and more college students, young mothers, and brides-to-be. And if the demand continues to increase, they may add classes for younger girls.

“Now, the men are the only ones left who’ll be fat,” Ahmed said.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!