Scientists taking closer look at how critical hearing is

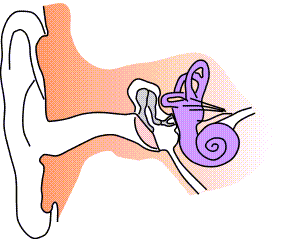

Ears hear the sound and the brain processes the sound. (Photo by Iain Fergusson via Wikimedia Commons.)

Thr world formed by the senses is becoming increasingly important to neuroscience.

And when it comes to hearing it’s no longer about the mass of volume or sound.

Seth Horowitz, an auditory neuroscientist at Brown University and author of “The Universal Sense: How Hearing Shapes the Mind,” says when we hear we aren’t just hearing what we need to hear. We also hear what’s surrounding us — potential information sources or sources of problems in our environment.

“For many years it was thought that a lot of animals were just sort of mating detectors, they just heard the sounds of their own species,” he said.

But one of Horowitz’s colleagues pointed out that if an animal only hears when it’s own species makes a sound it’s likely to be eaten by a predator.

It’s become a sort of auditory arms race, Horowitz says, between environmental detection of what sounds you can pick up and what your brain can comprehend.

“When you get to humans or primates, we have a lot of additional processing material, so we tend to have quite ornate auditory communication,” he said.

Bats are another example of a species with highly developed auditory ability, because they build their world from sound. Although a bat’s brain is the size of a peanut, Horowitz says they build a three-dimensional model of the world through sound.

“It’s not the mass (of sound), it’s not the volume, it’s what you do with it,” he said. “You have to get past the ears and into the brain to start parsing out what part of the sound is important.”

But for people or animals that no longer hear, Horowitz says the brain is very flexible and changeable. If you lose any sense, the brain will start to invade the unused areas if they aren’t damaged and use them for other things.

“Someone who goes blind will have better auditory response. Someone born deaf has never had an auditory experience but often they have better visual attention. Someone who loses hearing rapidly will also see that kind of shift,” he said.

One of the problems humans and other mammals face is high frequency hearing loss when we age, Horowitz says. And oftentimes those who lose their hearing at the high end of the spectrum don’t realize it.

“They’re constantly thinking people are muttering or not (speaking) clearly,” he said. “And a lot of older people, some diagnosed as having paranoia or dementia, a lot of it has to do apparently with hearing loss. They really can’t hear what’s going on anymore, but they’re convinced that they can.”

And though humans are visual creatures, it’s a slower process, Horowitz says. But the brain processes sounds 10 to 100 times faster than it can things it sees. And the brain is capable of picking signal out of noise through sound than it can visually, he says.

“Something that’s relevant or familiar or might be important you will pull out. If you’re in fact at a crowded cocktail party and someone says your name from across the room, you’ll hear it,” he said.

As for the future science of the brain, Horowitz says, stem cell technology is going to be an amazing tool for restoring hearing. And scientists are beginning to put all the pieces together to better understand the multisensory world.

“Because you don’t just hear, you don’t just see, you don’t just touch, you form the world from all of your senses integrated together. And that’s the revolution that’s beginning to happen in neuroscience,” he said. “Our technology has (become) good enough that we’re beginning to see the brain not as a series of parts but as a whole.”