New documentary looks at development of skateboarding culture in East Germany

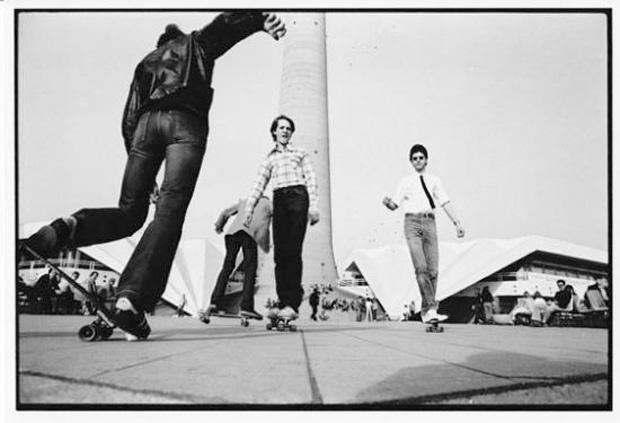

This scene from the documentary “This Ain’t California” shows what skateboarding was like in East Germany. (Photo by Harald Schmitt.)

Southern California may be the birthplace of skateboarding culture, but the sport also found a home thousands of miles away.

In the 1980s, teenagers in East Germany fell in love with skateboarding. They mostly got their information about it by word of mouth and in magazines smuggled across the border.

Now, a new documentary, called “This Ain’t California,” documents that time.

The film shows a lot of what you would expect in a skateboard flick — guys cruising down sidewalks, attempting crazy tricks, and taking hard falls. But it isn’t just a skater fan film.

It is also a look at what life was like for teenagers in East Germany.

“What I can remember is that I was one of three guys in the class that were a little bit different,” said Ronald Vietz, one of the producers of the film. He grew up in East Berlin in the 1980s.

Vietz remembers how difficult it was to be different as a teenager. News and entertainment from the West were banned. Anyone who rebelled was monitored by East Germany’s secret police, the Stasi.

He says it was totally isolating.

“West Germany was right next to us in West Berlin but it was already so far away, you couldn’t imagine how far it was,” he said.

And California was in another universe, hence the film’s name “This Ain’t California.” But despite all the restrictions, East German teenagers still discovered one of the big trends hitting the United States and Western Europe. Vietz remembers the first time he saw skateboarders in East Berlin.

“There were a group of 20-year-old guys sitting on Alexanderplatz and they had bandanas on their heads, and we thought ‘wow these guys are so cool.’ Where they coming from? Are they from the West?” Vietz said. “But they were just East guys dressed like West guys.”

The film focuses on a small group of skateboarders in East Berlin. Martin Persiel, the film’s director, said because materials were in short supply, they built their own boards and developed a unique style of skating.

“They didn’t have anyone telling them how to skate so they just skated the way they think is right. Maybe they saw it in some sort of photo from a friend that got a magazine smuggled over,” Persiel said.

These teenagers got some help from skaters in the West who started sending them used skateboard parts. Persiel says it was these friendships that finally drew the unwelcome attention of the East German government.

“In the beginning, it was that this is a western sport that we don’t need and we don’t want and it is bad,” he said.

The thinking changed once East German officials grasped the sport’s popularity. They tried to control skateboarding by creating clubs with training schedules and uniforms.

“The skaters didn’t accept this or use this offer from the state because they knew what it was about. It was about surveillance,” Persiel said.

The film was screened recently at a skateboard trade show — held in a former Stasi office building in Berlin. Outside, professionals practiced jumps. The audience included Americans and Germans. Among them were Kenny Faith from Pennsylvania and Christin Haussmann from Dresden, Germany. Haussmann, who was born a year before the Berlin Wall came down, said it was really interesting to see what was going on in East Germany.

Vietz wants to show people like Haussmann the reality of growing up in East Germany. For him, the film is as much about skateboarding as it is about remembering his childhood.

“It was a hard time and looking back doing that skateboarding film as a former East guy, it’s like talking about a country that doesn’t exist anymore,” Vietz said. “You know, when you are from any other country, from America, from Turkey, from wherever, you have a place to go back to, but we as East Berliners and East German people, we can’t go back to the country we’re from.”

After the Berlin Wall fell, East Germans had to adapt quickly to a world they had been sheltered from for decades. But Vietz says it was something he, as a skateboarder, was ready for.

He knew how to get up and keep going after a big fall.