Mother of deceased lead singer from Thin Lizzy discusses musician’s early life

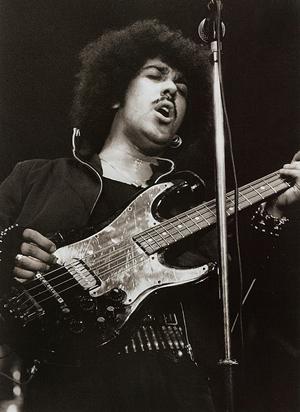

Phil Lynott, pictured in 1983, was born into difficult circumstances. His mother had her parents raise him. (Photo by Harry Potts via Wikimedia Commons.)

At the Republican National Convention in August, vice presidential nominee Paul Ryan took to the stage to the strains of Thin Lizzy’s The Boys Are Back in Town.

The lead singer of the Irish rock band, Phil Lynott, died in 1986 after abusing heroin. But his mother, Philomena Lynott, says her son wouldn’t have endorsed the Republican ticket.

It’s just the latest in a series of conflicts between politicians and pop culture icons. Sesame Street, for example, cried foul when the Obama campaign used Big Bird in a campaign ad critical of Mitt Romney, who’s said he would end subsidies for PBS.

As for Lynott, now 81, she’s been outspoken, since the early years of her life.

In the 1940s, Lynott was living in the English city of Birmingham. She’d left Ireland to take a job there as a nurse, and in the evenings she’d go out on the town.

“I used to go dancing,” she said to the BBC, “and while I was at the dancehall one night, a very tall dark man walked right across the whole room and asked me to dance. And I did.”

The man was black, from Guyana. He was in the military, Lynott remembered, and when the pair came off the dance floor together, everyone else moved away. There wasn’t much tolerance for that back then, let alone for an ongoing relationship.

“When you got on a bus or anything people looked at you like you were vermin because you were in the company of a black man,” she recalled. “It was horrendous: I was only 17 or going on 18.”

Soon she was pregnant. But Lynott couldn’t tell her family back in Ireland, so she looked for other options.

“I remembered an old wives’ tale that if you bought a little bottle of gin and you got some copper pennies, and if you boiled the gin and threw the pennies in and then sipped the hot spirit, that you would get rid of your baby,” she recalled. “But as the smell of the hot gin went up my nostrils I started dry retching.”

Lynott felt so sick she couldn’t get the gin down. Some months later Phil Lynott was born. At that moment, his father had moved on and was unaware of the birth. Mother and son went to live in a home for unmarried women in Birmingham.

It was operated by an order of nuns.

“I was the only one with a black baby, and they battered me, spat on me,” she said. “The nuns gave me the worst job in the whole world. It was winter, they put me outdoors in sort of a big shed where all the washing got done for the home. And I was in charge of washing all the (diapers). Nobody cared.”

The nuns pushed Lynott to give her son up for adoption. She refused and sent a letter to her mother in Ireland, including a photograph of her biracial son.

“They had to put her to bed, the shock she got. But eventually my Mammy and Daddy said they would take him and rear him,” Lynott said. “They hid it from everybody that he was mine. They said he belonged to an African lady who had died.”

So, Phil Lynott was raised by his grandparents rather than by his mother. Lynott says she was a more of a big sister than a Mom. And, she says, years later, she missed the signs of serious drug abuse in her son.

She says she didn’t notice because he was touring all the time. When he’d been touring he’d put on weight, so Lynott figured he was healthy. Phil Lynott died in 1986 at the age of 36.

“They didn’t want me there when he passed because they figured I’d lose my reason, which I did,” Lynott said. “When he died I died for five years. I think it’d be a dreadful waste, but what can you do? What will be will be.”

A couple of years ago, Lynott revealed that she’d had two other babies, a boy and a girl, and had given them both up for adoption. It was a secret she’d kept for half a century.

When the two became adults, they located Lynott and made contact. Lynott said she built good relationships with both her children.

With all three, if you count Phil.

“I listen to his music every single day,” she said. “I also visit his resting-place every day because it’s only round the corner from my house. I go around and I pour water on his stone — I call it washing his face — and then when I’m leaving I give him a kick, for breaking my heart.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!