A History of Political Trials

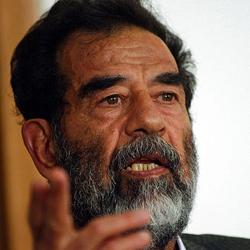

Saddam Hussein on trial in 2004 (Image: US Defense Dept)

By Arun Rath from PBS FRONTLINE

When former heads of state are put on trial, the proceedings carry a lot of baggage. Victims of the regime will want to testify, and desires for retribution have to be balanced with the requirements of true justice. Without at least the trappings of civilized law, history will forever question the legitimacy of the proceedings.

But too often, trials of former tyrants degenerate into scenes like the hanging of Saddam Hussein in December 2006. The scene, captured on illegally shot cell phone video, is best described as a revenge-driven lynching.

It’s chaotic and grotesque, with a crowd shouting ‘Muqtada! Muqtada!” — because Hussein is being strung up by his blood enemies, the followers of Muqtada al-Sadr.

Michael Scharf of the Case Western Reserve University School of Law was a member of the international team of experts that provided special training and assistance in the Saddam Hussein trial. That scene was not what Scharf envisioned when he set out to help the tribunal, and it tops a distinct list of lessons learned, advice he’d pass on to those trying Hosni Mubarak.

“Avoid the death penalty,” he said. “That way you can get international assistance and support for the trial. I wouldn’t televise this trial; because once you televise it you’re opening it up to all sorts of problems. I would make sure the defense has all the rights you need for a trial to be fair and there cannot be seen to be any interference from the government — because in the end, that was the downfall of the Saddam Hussein trial.”

So far, the Mubarak trial is two for two on that list of “don’ts”: The death penalty is on the table, and it’s already being televised.

“The problem is, once you televise you open a Pandora’s Box,” said Scharf. “The defendant has a place to make all sorts of arguments, not necessarily legal ones.”

The irony is the public trial can give tyrants a bully pulpit. Saddam Hussein used his perch as his own lawyer to give speeches when he was supposed to be cross-examining witnesses.

In a notorious speech from March of 2006, he exhorts the country to unite, purify their hearts and fight the foreign occupiers. The speech was broadcast across the whole country, and many believe it helped fuel the insurgency.

“What we saw during that trial was the civil war simmer, and explode,” Scharf said.

But even with all the problems of the Saddam trial, Scharf believes trying former dictators is essential for a country emerging from tyranny.

“If a trial can be a vehicle … where the victims feel like they have a cathartic moment, if they feel the moment is credible, it can be something that moves the country forward.”

John Laughlin, the director of studies at the institute for Democracy and Cooperation in Paris, suggests such claims are “complete rubbish.” His latest book is a history of political trials from Charles I to Saddam Hussein.

“This whole tendency is the polar opposite of the much more traditional notion, that it is the amnesties, the forgetting, that heal societies.”

Laughlin believes these sorts of trials don’t provide justice and only appeal to the worst in people. “It’s not by digging up grievances from the past that societies will achieve peace,” he said.

Scharf concedes that most of these trials have been divisive. But digging up crimes from the past doesn’t always lead to national conflict.

In 1980, South Korea’s defacto leader, Gen. Chun Doo-hwan brutally suppressed an uprising in Gwangju province. Estimates of civilian casualties ranged from the hundreds to the thousands.

Chun voluntarily handed over power to a democratically elected government in 1988. And it wasn’t long before the country he led turned against him.

“There was a government sanctioned official investigation starting in the mid-1990s,” said Sung-yoon Lee, an expert on the history of the Korean peninsula at Tufts University. “There was a trial a few years later in 1996. Chun Doo-hwan was found guilty of various crimes — insurrection, conspiracy, killing of civilians — and he was actually sentenced to death.”

In a bizarrely poetic twist, Chun was pardoned at the behest of incoming president Kim Dae-Jung — who had himself escaped a death sentence under Gen. Chun in the 1980s for his role in stirring up unrest in Gwangju.

It’s not hard to find Koreans who still hate Chun, especially among survivors of the Gwangju massacre. But Lee said, “today South Koreans do not revile him — in fact I forsee a more revisionist appraisal coming for Chun Doo-Hwan in coming decades for his role in growing the economy. If you eliminate his bribery and his role in the Gwangju massacre — two major offenses, of course — then his presidency really comes across as a success.”

Chun Doo-Hwan still has a loyal following, no doubt because of that success — during his tenure, the standard of living for South Koreans rose dramatically.

If Hosni Mubarak had done more to raise the quality of life for the average Egyptian, today’s proceedings in Cairo might not be happening at all.