Colombia’s Latest Tack Against Drug Production

(Photo: John Otis)

by John Otis

To produce a kilo of 90 percent pure cocaine, you need more than just coca leaves, the raw material for the narcotic. You also need a long list of chemicals, such as sulfuric acid, caustic soda, and acetone.

In fact, chemicals are the most expensive part of making cocaine, according to Jay Berman, chief of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Andean division.

“It’s not the coca leaf, it’s not the workers, and it’s not the cost of building the cocaine laboratory,” Bergman said. “The number one cost is the chemicals.”

So authorities are engaged in a campaign against “precursor chemicals” that can be used in the production of methamphetamine, heroin, and cocaine.

Bergman said that cutting the chemical supply line to meth labs in Mexico and cocaine labs in Colombia can have a huge impact.

“A cocaine HCL lab will shut down for a period of time not because of lack of access to the coca leaf but to the actual chemicals that they need to refine it into hydrochloride, cocaine HCL.”

Legitimate Uses

Yet the task is daunting because these chemicals also have legitimate uses, and they’re everywhere. Potassium permanganate, for example, can purify cocaine. But it’s also used to treat wastewater, disinfect animal skins and prevent bananas from ripening too fast.

Acetone is a key ingredient in both cocaine and house paint.

And many consumer goods can be used to make cocaine, according to Major Carlos Oviedo of Colombia’s anti-narcotics police. That includes motor oil, gasoline, kerosene, lime, cement and baking soda.

Sales of these items are strictly controlled in southern Colombian towns located near cocaine labs, Oviedo said. Gas stations are banned from selling more than 55 gallons per day to a single customer. The personal limit on baking soda is 11 pounds a month.

Colombia has some of the strictest regulations in the world on the amount of precursor chemicals that firms are allowed to buy, sell and consume. But traffickers can bribe company employees or steal the chemicals.

In one infamous case, four guards were killed in Mexico during the theft of a ton of ephedrine, which is used in the production of methamphetamine. It’s also easy for shady companies to order more than they need and then sell the excess to drug cartels.

Monitoring Chemicals

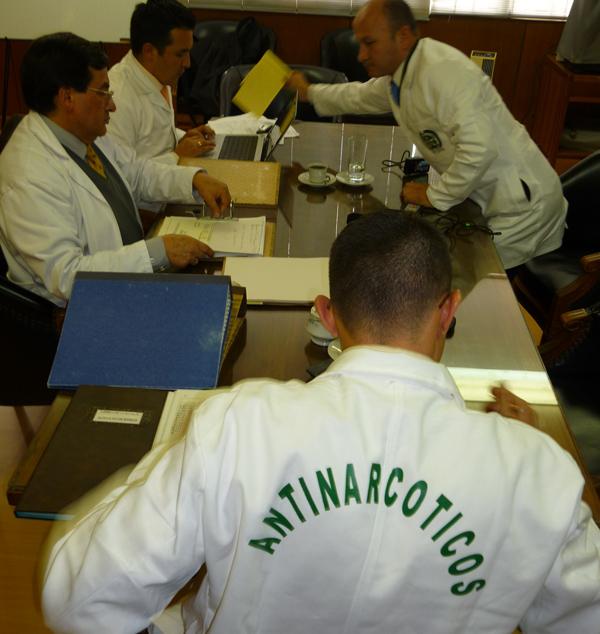

That’s where Luis Saavedra comes in. He’s part of a Colombian police unit that monitors chemical use at hundreds of industrial firms.

On this day, Saavedra is inspecting the Hartung cosmetic company, which uses 24 tons of precursor chemicals every month.

As workers pluck bottles of nail polish remover from a conveyer belt, Saavedra checks the plant’s tanks. They’re full of butyl and ethyl acetate, powerful solvents used in nail polish remover but which can also be used in cocaine.

Saavedra finds nothing suspicious. But the crackdown has forced Colombian traffickers to relocate some of their drug labs to Central America, said General Cesar Pinzon, chief of Colombia’s anti-narcotics police. He said that in March, police in Honduras raided a huge drug lab stocked with acetic acid, calcium chloride and acetone. It was the first major cocaine lab ever discovered in Honduras.

“The traffickers are sending unrefined cocaine to countries where there are no controls over precursor chemicals,” he said.

Once the drugs are processed, the toxic waste is simply dumped into the jungle where the chemicals find their way into rivers and groundwater. In fact, police were tipped off to the cocaine lab in Honduras after farmers complained about contamination of their water supply.