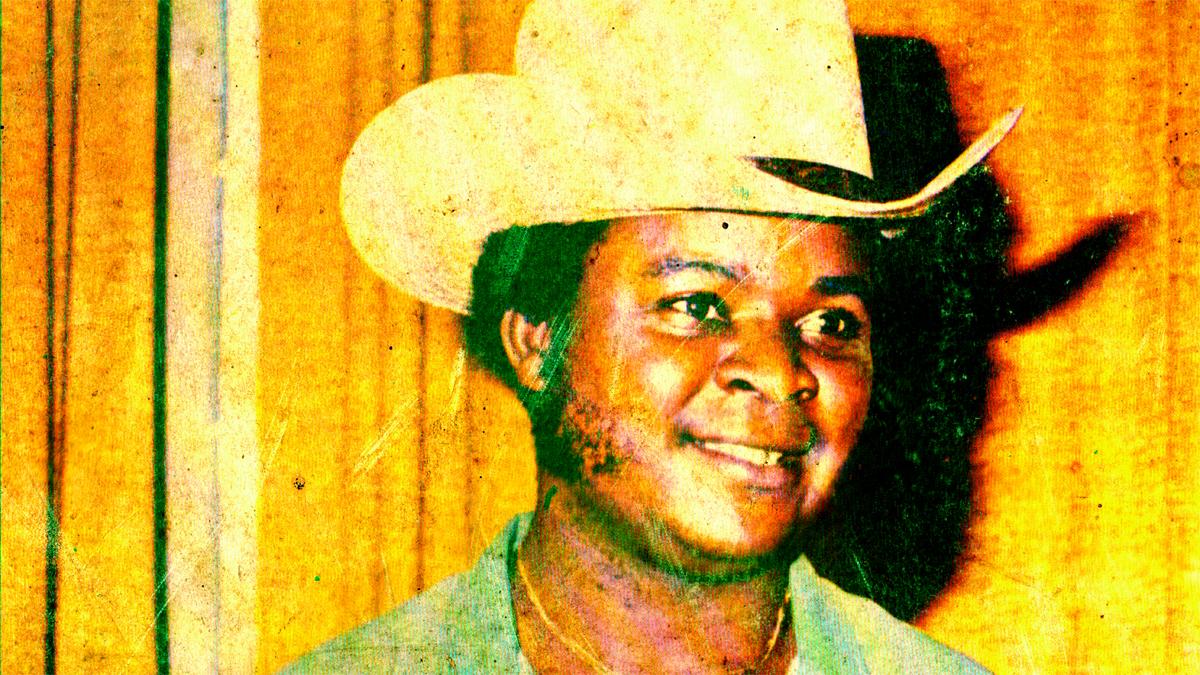

William Onyeabor won’t answer the question ‘Who is William Onyeabor?’

William Onyeabor

William Onyeabor made homemade synthesized dance music like nothing you've ever heard. It's as though his recordings from the 1970s and 80s foretell dance sounds from 2015. In other words, you wouldn't have heard this kind of dance music for another few years if William Onyeabor hadn't recorded these tracks some 30 years ago.

That's one of the few things we do know about this music. There is precious little information or any notes on any of the recording sessions. And Onyeabor doesn't want to say much else about it. He won't say why, either. Just doesn't want to go there.

Luaka Bop records, David Byrne's boutique globally-minded imprint, last month managed, after more than four years of negotiations, to secure a deal with Onyeabor to release a collection of his often-bootlegged tracks. Eric Welles, the label manager, knows a bit more than anyone about Onyeabor.

"He wanted to have a one-man band and tried to do everything himself electronically," explains Welles. Musically, it was that idea of making electronic music, and making it yourself, says Welles, that "really differentiated him from a lot of musicians in that part of the world at that time."

Onyeabor is admired by purveyors of cool, like Devendra Banhart and Damon Albarn. But they're admiring a finite output. Onyeabor no longer makes music. He's now a born-again Christian. And doesn't talk much about his life before Christianity.

He attended film school in the ex-Soviet Union in the 70s. But it's hard to get him to talk about that, too.

Eric Welles became the Luaka Bop emissary dispatched to Onyeabor's home of Enugu, Nigeria to learn more about him. Onyeabor greeted Welles. And Welles was prepared: he had been briefed by people who had met Onyeabor that if he tried to flatter or charm him, "Onyeabor would break my neck and ask me where the money is."

Getting to the bottom of William Onyeabor would prove to be an exercise in futility. As Welles explains:

"When we put out a record, we try and tell an artists' story, and to create something special around the music. So how do we approach that if we have an artist that doesn’t want to talk about the music?"

So, with a list of 100 questions that he mostly could not ask Onyeabor, Welles and his host spent the better part of a week in Enugu sitting in front of the television in Onyeabor's early 1980s-decorated home watching a Nigerian evangelist by the name of TB Joshua.

"The town of Enugu is heavily evangelical, so everyone in this town is basically a born-again Christian," says Welles. "So when you go around town or if you meet someone somewhere, they’ll most likely ask you if you’re born again."

With no solid backstory to the man, there is still plenty to connect with in Onyeabor's music.

"Just listen and enjoy, and take time to listen," advises Eric Welles. "The structure of Onyeabor's music may feel really rigid, but at the same time, it's incredibly free, like the song 'Atomic Bomb.' Or a song like 'Let’s Fall in Love' is just so far out there. I used to listen to that on the West Coast. In the spring, driving in the desert, I'd put that song on and it just blew my mind every time."