Remembering Martin Luther King and the March on Washington

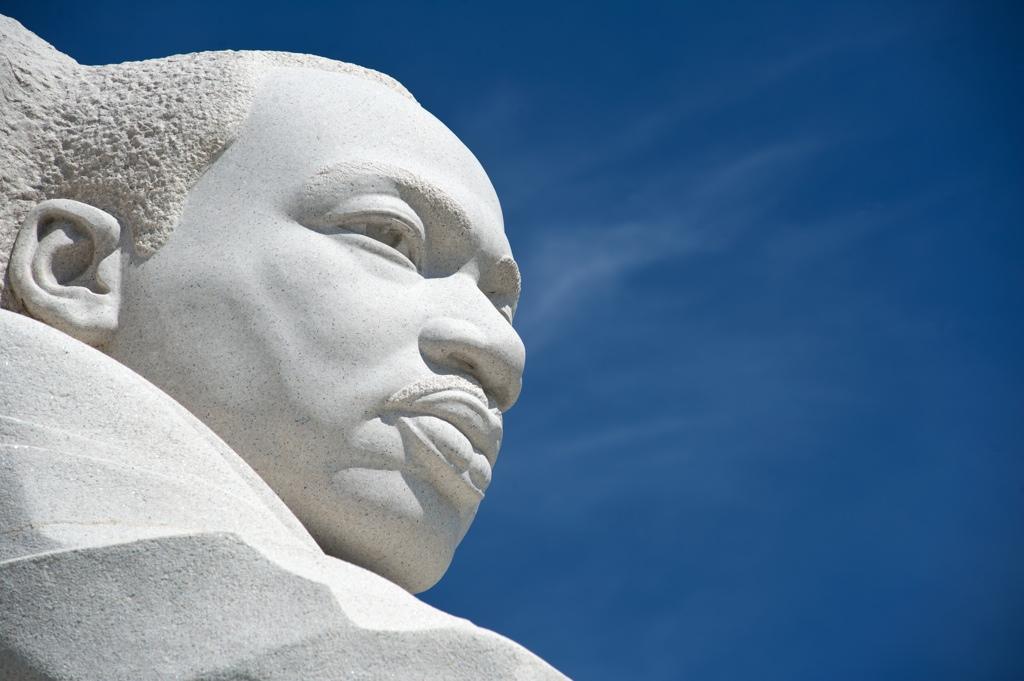

The statue of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. is seen at the MLK Memorial in Washington, DC.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — What’s largely forgotten now, in the plethora of articles and books about the great “March On Washington for Freedom and Jobs” 50 years ago this month, is the fear it engendered among many white people in the nation’s capital.

There had never been anything quite like it before, and the thought of black people in the tens of thousands descending on Washington was alarming to some.

Many whites were planning to leave town the day of the march. The specter of riots, of looting, of cars being turned over in the streets, of dark people rampaging through the quaint by-ways of Georgetown where so many of the powerful resided, was being raised at dinner parties in the weeks and days leading up to the event.

John F. Kennedy was in the White House, and although his heart was in the right place concerning civil rights, he was nervous about the politics. The great transformation of America’s political parties had not yet taken place; the Democratic Party had many southern conservatives, senators and congressmen, in its ranks.

The racial battles of Birmingham, Alabama, had caught the nation’s attention in May 1963, and Martin Luther King hoped that a March on Washington would embolden JFK to propose serious civil rights legislation. It did.

But as the day of the march approached, Washington was as nervous as when “a fox first hears the hounds,“ as one Washingtonian told me then. I was working for Time magazine, a news organization that held much more sway over the national dialogue in those pre-internet days when not even TV had replaced print as the source of news for most Americans.

Time’s large Washington bureau was deployed to cover the event, and although I was just a junior member, I was delighted to receive an assignment on the mall itself where Martin Luther King would address the multitudes.

And multitudes there were. I had never before seen anything like it. First there were the busses, parked along the streets, hundreds and hundreds with license plates registering most of the states in the country. There were more than 200,000 upturned faces under the Washington Monument and spreading out to the Lincoln Memorial, most of them black, but interspersed with whites, too, who had decided to join the movement.

King was becoming a superstar, and the cadence of his speech, steeped in the traditions of the black church, was in its way as inspiring as Winston Churchill’s voice had been in the dark days of World War II 20 years before. My yellowing notebook recorded that he repeated the iconic phrase “I have a dream” nine times, his voice echoing out over the reflecting pool, out over Washington, and down through the decades to take its place as one of the most important and memorable speeches in American history.

What impressed me at the time were the conciliatory passages. This was a call for action, but not for violence or sedition.

“Here is something I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads to the palace of Justice,” King said on that steamy summer day. “In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.”

With a nod to the statue of Lincoln, he said that "negroes" — as black people were still called then — had been given a blank check, but the check had come back marked “insufficient funds.” Now it was time for America to make good on its promise.

“With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.”

It was a thrilling moment. All the fears of frightened whites had proved foolish; tens of thousands had expressed their desires peacefully. I sensed at the time that a great sea change was upon us, that America would become a better place.

Later that year President Kennedy would be assassinated, and then Martin Luther King, too. His statue, hewn out of the mountain of despair, stands today near where he spoke. The discords of our nation are still jangling, and not everything in King’s dream has taken place. But not even King could have dreamed that within half a century a man like Barack Obama could occupy the White House.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?